While malnutrition is a global plague, it is a more acute problem in Asia.

According to a report by the World Health Organisation (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and World Bank Group published last year, more than half of all stunted children, almost half of all overweight children and more than two-thirds of all wasted children live in the region.

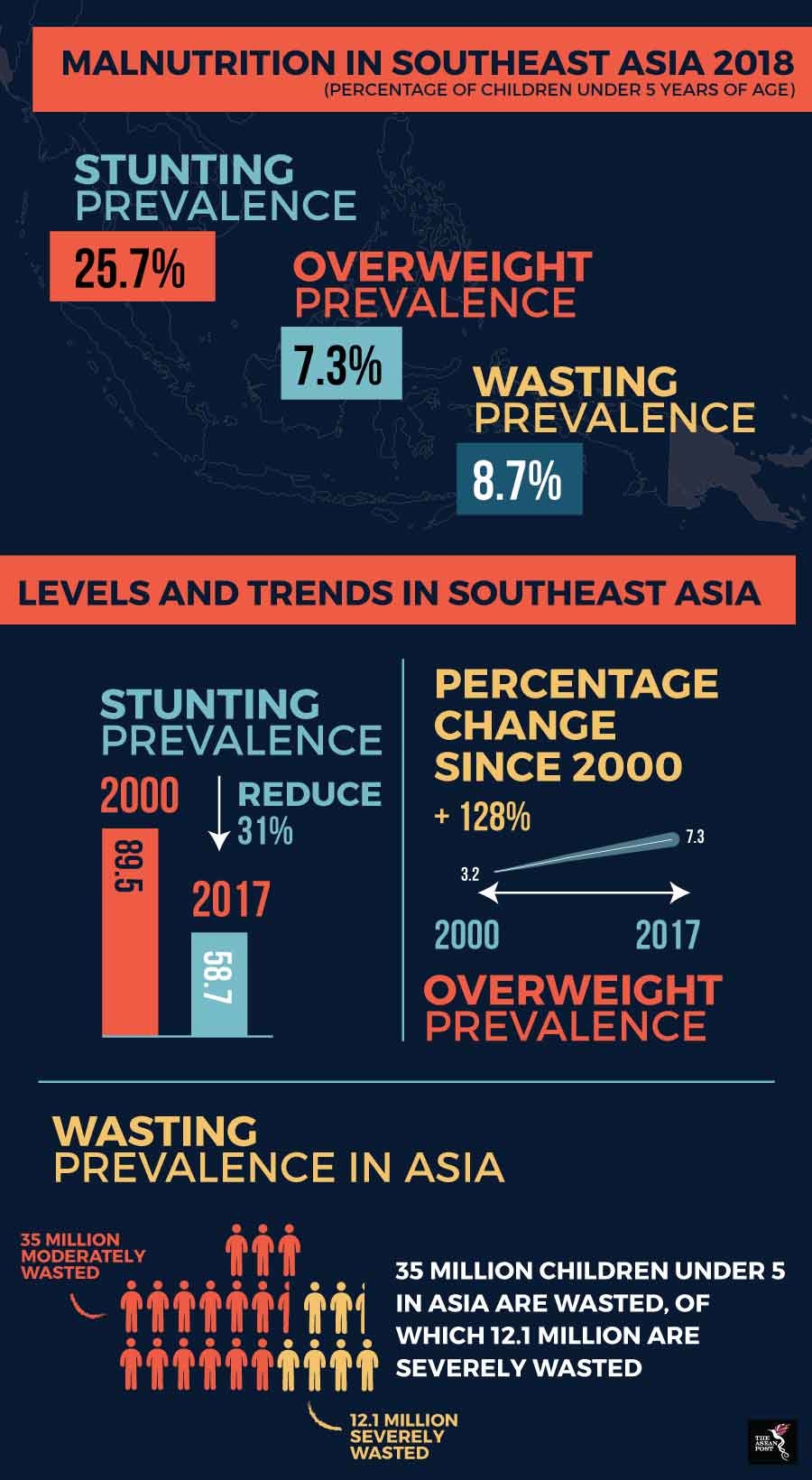

Zooming into Southeast Asia, the results are, unfortunately, not too surprising.

The report titled ‘Levels and trends in child malnutrition 2018’ found that 25.7 percent of children under five in ASEAN are stunted while 8.7 percent and 7.3 percent of children under five are wasting and overweight, respectively.

Defining The Problem

According to the report, stunting refers to a child who is too short for his or her age. These children can suffer severe irreversible physical and cognitive damage that accompanies stunted growth, and the devastating effects of stunting can last a lifetime and even affect the next generation.

Wasting refers to a child who is too thin for his or her height and is the result of recent rapid weight loss or the failure to gain weight. A child who is moderately or severely wasted has an increased risk of death, but treatment is possible.

Children who are overweight are often too heavy for their height. This form of malnutrition results from energy intake from foods and beverages that exceed a child’s energy requirements, and being overweight increases the risk of diet-related noncommunicable diseases later in life.

It is a concern that these issues of malnutrition, especially stunted growth, are still prevalent in most countries in the region – even in those that are seen to be enjoying positive economic growth. In addition to poverty, other contributing factors include traditional diets that lack food with sufficient nutrients, poor infant feeding practices, inadequate clean water and sanitation and limited agricultural crops.

Malnutrition In The Region

Malnutrition can affect the lives of children, and indirectly, the economy of a nation. Children who are suffering from acute malnutrition will suffer from slow or poor brain development and develop cognitive damage. This would then affect their performance in school and in turn, limit their prospects in the job market. This, of course, will also affect the country’s economic growth.

Apart from the child itself, malnutrition also affects parents indirectly. Malnourished children get sick more often and this can reduce parents’ productivity as well as create a burden on the health care system. It can also lead to non-communicable diseases, disability and even death, reducing the workforce of a country. According to a 2016 estimate from UNICEF, the economic cost of non-communicable diseases in Indonesia – much of which is diet-related – was estimated to be US$248 billion per year.

How Can ASEAN Tackle This Issue?

According to the UNICEF Regional Report on Nutrition Security in ASEAN (2016), these forms of malnutrition “can be prevented when sufficient political will enables the necessary coordinated actions: food security, adequate healthcare, clean water and sanitation, education on healthy choices and lifestyles, and poverty reduction.”

In 2015, all 10 ASEAN member states, along with 183 other countries worldwide, adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Good nutrition is embedded in many of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These include SDGs related to hunger, health, education, water and sanitation, poverty, women’s empowerment, and sustainable management of natural resources.

Nutritional security and fortification require collaboration from all stakeholders in various sectors such as respective governments, schools and civil-society organisations to ensure one of the most fundamental rights of children – which is the right to food and nutrition – is guaranteed.

Some ways in which ASEAN can tackle this issue include regulating the marketing of non-nutritious foods such as junk food and sugary drinks to children and to restrict their availability in schools. Apart from that, governments should also implement and ensure that good hygiene and sanitation levels are met alongside investing more towards tackling the problem of malnutrition in the region. From its report, UNICEF suggests that governments should also “map the situation of children in most at-risk areas, including poverty, malnutrition, and geographic vulnerability.”

This article was first published by The ASEAN Post on 3 February 2018 and has been updated to reflect the latest data.

Related Articles: