In recent years, smart technology has improved our lives for the better. ‘SMART’ refers to “self-monitoring, analysis, and reporting technology.” It is a technology that uses artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and big data analysis to provide cognitive awareness to inanimate objects.

Smart technology can be divided into a few different types, according to Rezaid, a Britain-based software firm. This includes smart connected devices where an object is controlled via a remote and connected to the internet using Bluetooth.

There is now a wide range of smart products such as a smart televisions (TVs), smartphones, smart eyeglasses, smart fridges – the list goes on. There are also smart devices which are considered ‘wearables’ such as the smart wrist bands, finger rings and earbuds.

Perhaps the most common type of wearable these days is the smartwatch. Unlike traditional watches, they are not designed to just tell the time. Internet access has enabled them with capabilities like receiving message notifications, calendar synchronisation and GPS navigation.

Smartwatches also commonly act as fitness trackers. They gather data about physical activity, heart rate and quality of sleep. Some of the popular wearable brands include Fitbit and Apple.

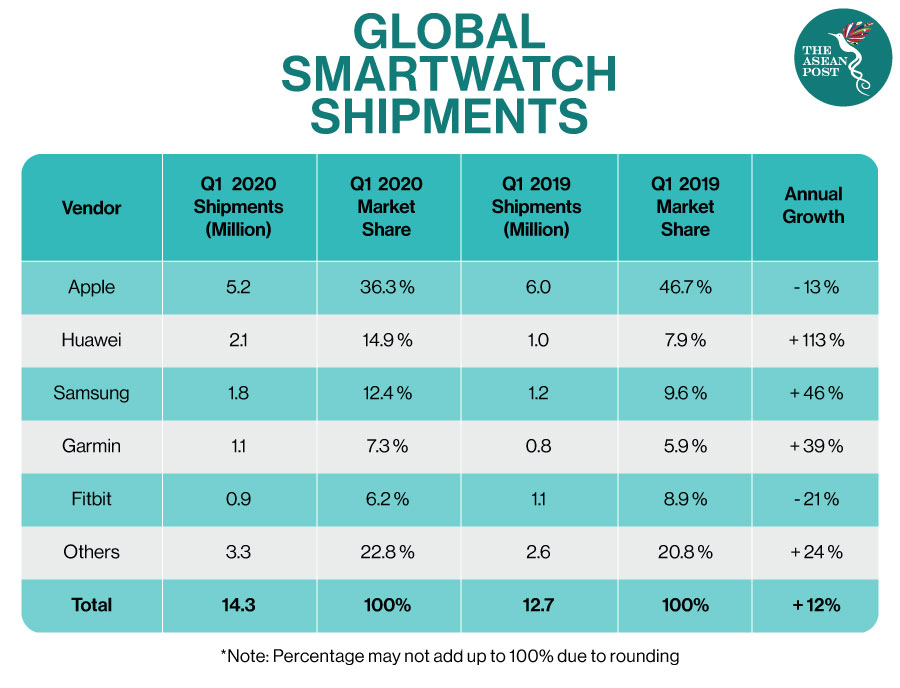

According to market analyst firm Canalys, it is expected that there will be over 150 million smartwatch users in 2020. Worldwide smartwatch shipments also grew 12 percent in the first quarter of 2020 despite the pandemic.

Infection Detection

The COVID-19 virus has infected more than 22 million people worldwide, taking with it close to 800,000 lives. Virus measures have been implemented across the world to halt the spread of the coronavirus. And like any other disease, the early warning of a possible COVID-19 infection is very important.

Urte Jakimaviciute, senior director of market research at Global Data said that wearable fitness trackers’ ability to monitor sleep patterns, activities and heart rates may make them a “game changer” in detecting COVID-19 symptoms.

“Given the highly contagious nature of the virus, early detection could prove crucial in minimising its spread while economies re-open and social distancing measures are scaled back,” said Jakimaviciute.

As wearables are great tools for monitoring general health conditions, studies about utilising them to detect illnesses have been carried out even before the pandemic began. For example, researchers at the Scripps Research Translational Institute conducted a two-year study and used Fitbit data to identify people who could have an influenza-like illness from their resting heart rate and daily activity patterns.

"It really significantly improved our ability to predict real-time influenza-like illness surveillance at the state level," said Jennifer Radin, lead author of the study who came up with the idea after noticing that her resting heart rate, according to her fitness tracker, was higher than usual when she was sick. It was reported than an elevated resting heart rate can be related to an infection.

It is, however, impossible to determine if a person has a particular disease just by using data from these devices. But, noticing sudden changes can perhaps drive people to isolate themselves and get tested.

One of the most common symptoms of COVID-19 is fever, hence the new normal of temperature checks at the entrances of most premises. Although temperature sensors in wearables are rather uncommon, some can measure sweat rate, which can be used as an indicator of temperature, wrote Albert H. Titus, Professor at the University of Buffalo. According to his article titled, ‘Wearable fitness devices deliver early warning of possible COVID-19 infection’, researchers are currently examining these sensors for use in helping to detect the deadly virus.

Wearables Use

Amid the health crisis, researchers are now looking at these smart devices as possible early warning systems for the coronavirus.

Back in June, scientists at the West Virginia University Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute announced that they had developed an app that can detect COVID-19 symptoms such as fever and coughing – up to three days before they show up using the Oura ring, a wearable fitness tracker. Other than that, Scripps Research enrolled over 30,000 people in a study aiming to use wearables to find “pre-symptomatic” and asymptomatic people with COVID-19.

Whereas in Germany, the public health authority in partnership with healthcare start-up, Thryve have launched a smartwatch app in March to help monitor the spread of the coronavirus and analyse whether virus measures are working.

Despite the promises of these smart devices, there are barriers to widespread use of wearables. Albert H. Titus noted in his article that most wearables are expensive, and can be difficult to learn and to use, or are developed without data from a broad population base.

“Ongoing research should result in improved technology that, with care, will benefit all of society,” he wrote.

Related Articles: