The COVID-19 crisis has ravaged livelihoods and the economy in general. Millions of people have suffered from job loss and wage cuts due to the economic shocks caused by the pandemic. However, it’s not just working adults that have been affected, but children as well.

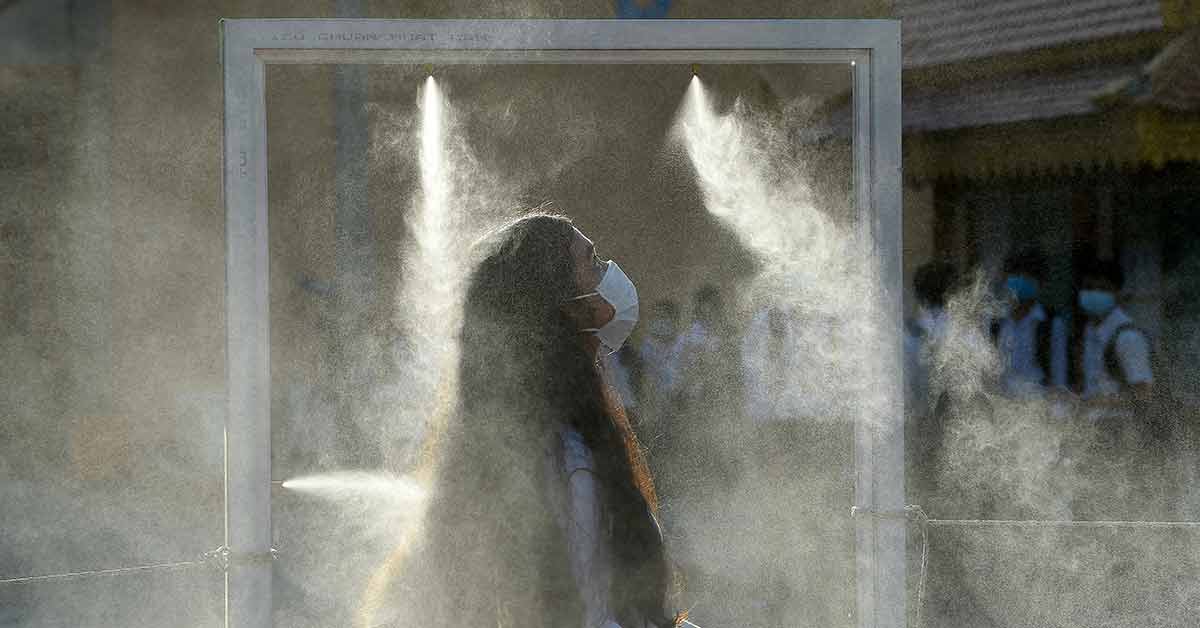

Alberto Muyot from non-governmental organisation (NGO) Save the Children Philippines said that children who live in poverty are the most exposed to shocks and calamities in urban settings. The pandemic – which is said to push a further 34 million people into extreme poverty by the end of 2020 – has further aggravated the situation of these children and their families. Some of them have to stay in cramped spaces, with limited access to water, clean toilets and hygiene facilities, making it difficult to comply with health protocols of social distancing and frequent handwashing.

Although some countries across Southeast Asia are gradually easing virus restrictions, the region still faces a continuing economic crisis with high unemployment rates. For example, ASEAN member state Singapore’s overall jobless rate was reported to have increased in the second quarter of the year to its highest level in more than a decade.

The resulting economic, psychosocial, and physical strain on families has increased incidences of physical abuse, early marriage, and child labour.

In addition, a survey conducted by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has revealed that seven out of 10 youngsters experience stress, anxiety and boredom from having to stay at home. It also found that more than half of them are worried about their education, exams and opportunities for further study due to school closures.

Digital Divide

According to Save the Children, the world’s children is facing an “unprecedented education emergency” as almost 10 million kids may never return to school following the coronavirus crisis.

“For the first time in human history, an entire generation of children globally have had their education disrupted,” the NGO noted in its report titled ‘Save our Education’.

“We are at risk of unparalleled budget cuts which will see existing inequality explode between the rich and the poor and between boys and girls,” said Inger Ashing, Chief Executive Officer of Save the Children.

“We know the poorest, most marginalised children who were already the furthest behind have suffered the greatest loss, with no access to distance learning, or any kind of education, for half an academic year,” Ashing continued.

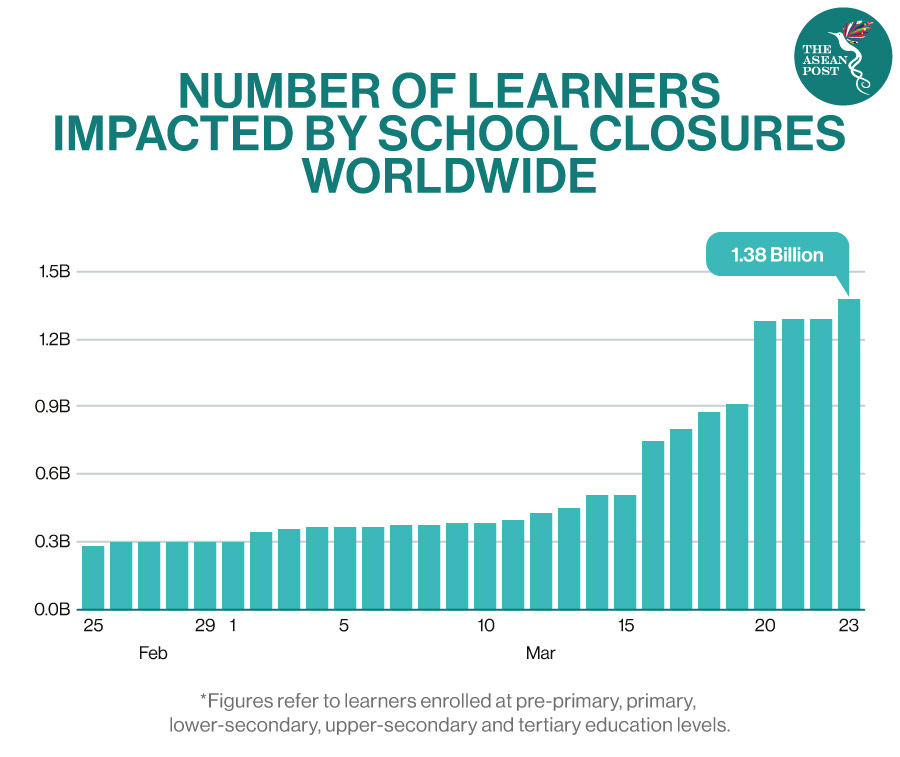

By April 2020, 188 countries around the world had imposed nationwide school closures, affecting more than 1.5 billion children and youth. As a result, many schools and institutions are now offering distance learning to their pupils. Unfortunately, not everyone has the luxury to opt for this.

The United Nations (UN) stated that while more than two-thirds of countries have introduced a national distance learning platform, only 30 percent of low-income countries have done so. Children living in informal settlements, camps with limited infrastructure and no access to the internet are especially impacted.

For example, the ability of Rohingya children to access quality education is severely restricted in Myanmar and in refugee camps elsewhere. The Burmese Rohingya Organization UK (BROUK) said that over 73 percent of Rohingya children in Rakhine state self-identify as illiterate. According to media reports, Rohingya children are often unable to attend mixed Rakhine-Rohingya schools and are kept in separate education facilities where the quality of education is limited. In addition, internet access in conflict-wrecked Rakhine is currently too slow for communication as 3G and 4G services are tethered.

Although studies have shown increased internet penetration over the years, millions of people in Southeast Asia still cannot afford unlimited and stable connections. For example, despite many having access to high-speed Internet in Kuala Lumpur, the capital city of Malaysia – some other states in the country experience a much slower internet speed. In fact, it was reported that some parts of the state of Sarawak in East Malaysia has no internet connectivity at all.

Which brings to attention the recent story of Veveonah Mosibin, a student from the East Malaysia state of Sabah who posted a video of herself having to climb a tree in order to sit for her exams online. The video went viral and has since prompted the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) to devise plans to erect a telecommunications tower in Veveonah’s village of Kampung Bilangau Kecil, Pitas to give her, other students and fellow villagers improved internet access.

Nuurrianti Jalli, Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Communications and Media Studies at Malaysia’s Universiti Teknologi MARA urged Southeast Asian governments to develop a proper action plan for pedagogy during times of crisis like the coronavirus outbreak by working closely with technology providers to ease the impact of school closures on education.

In her article titled, ‘Lack of internet access in Southeast Asia poses challenges for students to study online amid COVID-19 pandemic’, she suggested the introduction of an ‘affordable device program’ to ensure all families own at least one compatible device for online learning.

As people across the globe battle the COVID-19 virus and experience disruptions to their livelihoods – it is essential for learning to continue. For millions of children in the developing world, schools are the most promising pathway to well-paying jobs, careers and the ladder of social progress.

As simply stated by the 41st president of the United States (US), George H W Bush: “Education is the key to opportunity. It’s a ticket out of poverty.”

Related Articles: