The tech world was recently abuzz with news that Grab was in a favourable position to acquire its long-time rival, Gojek. Although this mega-deal is yet to be confirmed, it is nonetheless important for us to consider its potential ramifications on Indonesia’s digital economy.

This is especially critical since recent studies such as the United States (US) House Judiciary Report on Competition in Digital Markets have revealed how powerful tech companies tend to use strategies such as ‘killer mergers’ to eliminate their competitors and to monopolise the market.

In general, competition law prohibits mergers that result in markets becoming less competitive, as it may lead to adverse effects on consumers and businesses in general. For instance, Article 28 of Indonesia’s Antimonopoly Law states that “business actors are prohibited from conducting mergers which may cause monopolistic practices and unfair business competition”.

From a conventional antitrust analysis, the theory of harm is clear: the merger will result in Grab becoming a de facto monopoly.

New York-based technology research company, ABI Research reported that as of 18 September 2019, Grab and Gojek dominated the ride-hailing market in Indonesia; the former having 64 percent market share and the latter owning 35.3 percent. If they combine their market shares through a merger, Grab will control a whopping 99.3 percent of the market.

The real danger, however, is that this is not the end of the story. In traditional markets, even if a company becomes a monopoly, Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hands’ will work to constrain the monopolist’s exercise of market power.

So, for instance, if the monopolist raises prices to unacceptable levels, a new company will enter the market with lower prices to entice consumers away from the monopolist. Hence, over time the market will ‘self-correct’.

Grab and Gojek do not operate in traditional markets. The two platforms exist in digital markets with distinct economic features which may exacerbate the ills of an anticompetitive merger.

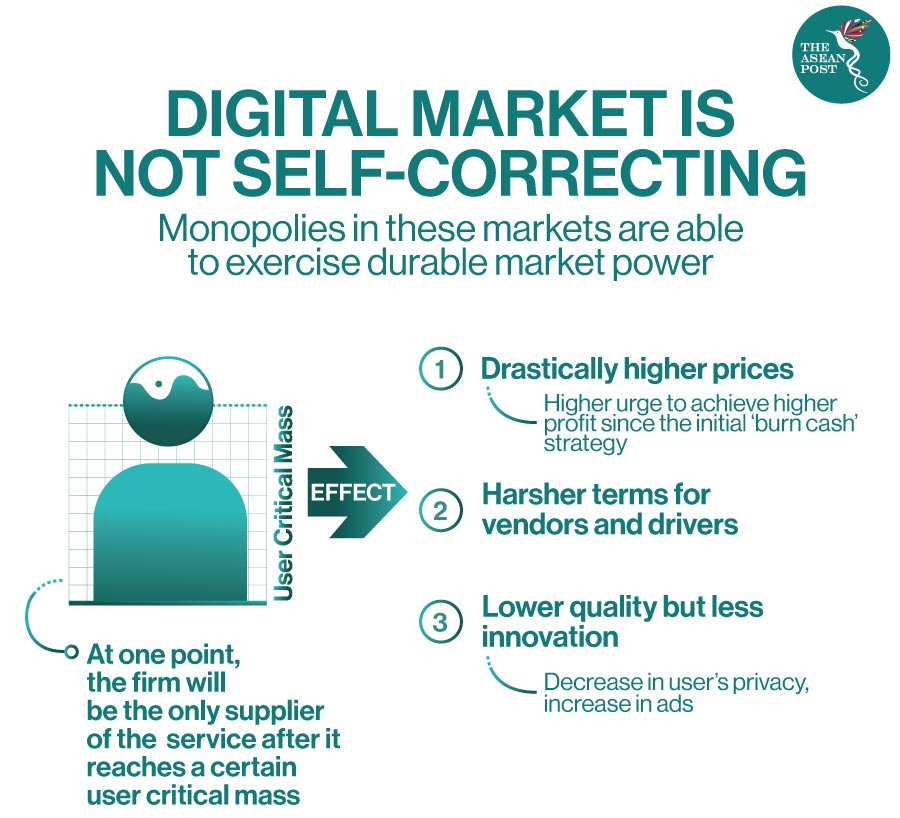

Indeed, the 2019 Stigler Committee’s Report on Digital Platforms warned that digital markets are not self-correcting and often have extremely high barriers to entry. As a result, monopolies in these markets are able to exercise durable market power. This is due to a unique combination of features which shifts the competitive process from competition ‘in’ the market to competition ‘for’ the market where the ‘winner takes all’.

As noted by the United Kingdom’s (UK) Expert Panel Report on Digital Competition, it is the combination of strong network effects and data-driven economies of scale and scope that makes digital markets vulnerable to tipping.

Thus, once a platform is able to reach user critical mass, it will become the primary (if not the only) firm to supply the service. This explains why Google’s overwhelming dominance in the online search market has remained unchallenged for over 20 years.

Dangers On Digital Economy

In light of these market dynamics, the Grab-Gojek merger may cause harm to millions of consumers and entrepreneurs in Indonesia’s digital economy.

First, consumers may see drastically higher prices. This is a natural outcome of all monopoly markets, since the incumbent will not face any price competition. Indeed, an article written in The ASEAN Post in 2018 confirms that shortly after Grab acquired Uber, there were numerous complaints that fare prices spiked after the merger.

Unfettered by any meaningful competition, it is entirely possible that the merged entity may even begin charging subscription fees for using their platform to extract higher profits.

Moreover, Grab and Gojek are multi-sided platforms which act as an intermediary for the demand-side (passengers) and the supply-side (drivers). The merged entity may seek to increase its profits further by imposing harsher terms on drivers and vendors, who will find it difficult to refuse due to the millions of users locked-in with the incumbent’s platform.

These profit maximising strategies are likely, given that Grab and Gojek have ‘burnt cash’ for years to acquire their massive market shares, and will be eager to recoup their losses.

Finally, consumers may experience lower quality service and fewer innovations. For instance, this could happen by introducing targeted ads in the apps to generate even more revenue, or by lowering users’ privacy protections so that the platforms can extract even more data which they can sell to advertisers.

In fact, Dina Srinivasan, a fellow at Yale’s Thurman Arnold Project, recently published a paper explaining how Facebook’s data collection became even more aggressive after facing less competition from MySpace.

Of all these dangers, perhaps the most worrying is that there is nothing Indonesia’s competition authority (KPPU) can do to stop the merger. This is because Article 29 of Indonesia’s Antimonopoly Law establishes a post-merger notification system, where mergers are only required to be notified within 30 days after their completion. Although the KPPU can annul mergers under Article 47, they cannot block mergers before they take effect.

Therefore, this should be seen as a wake-up call to Indonesia’s lawmakers to promptly revise the country’s outdated antimonopoly laws so that these archaic deficiencies do not stand in the way of the KPPU’s duty to safeguard markets.

Otherwise, we may all end up paying the price...literally.

Related Articles: