Vietnam was issued a yellow card in October 2017 by the European Commission (EC) because of its faint attempt to eliminate illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. According to its carding system, the EC has conducted several reviews of Vietnam’s fisheries and seafood-related policies and efforts to determine whether the yellow card would be maintained or rescinded.

The first round of inspections took place in May 2018, but only leading to a six-month extension of the yellow card. In November 2019 the EC’s Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries sent inspectors to Vietnam for a second round of review, but the result did not change Vietnam’s yellow card status.

Shortly afterwards, two virtual meetings held between the EC and Vietnam were organised in June and October 2020, respectively to review Vietnam’s progress. However, the result disappointed both sides.

EC’s Requirements, Vietnam’s Frustration

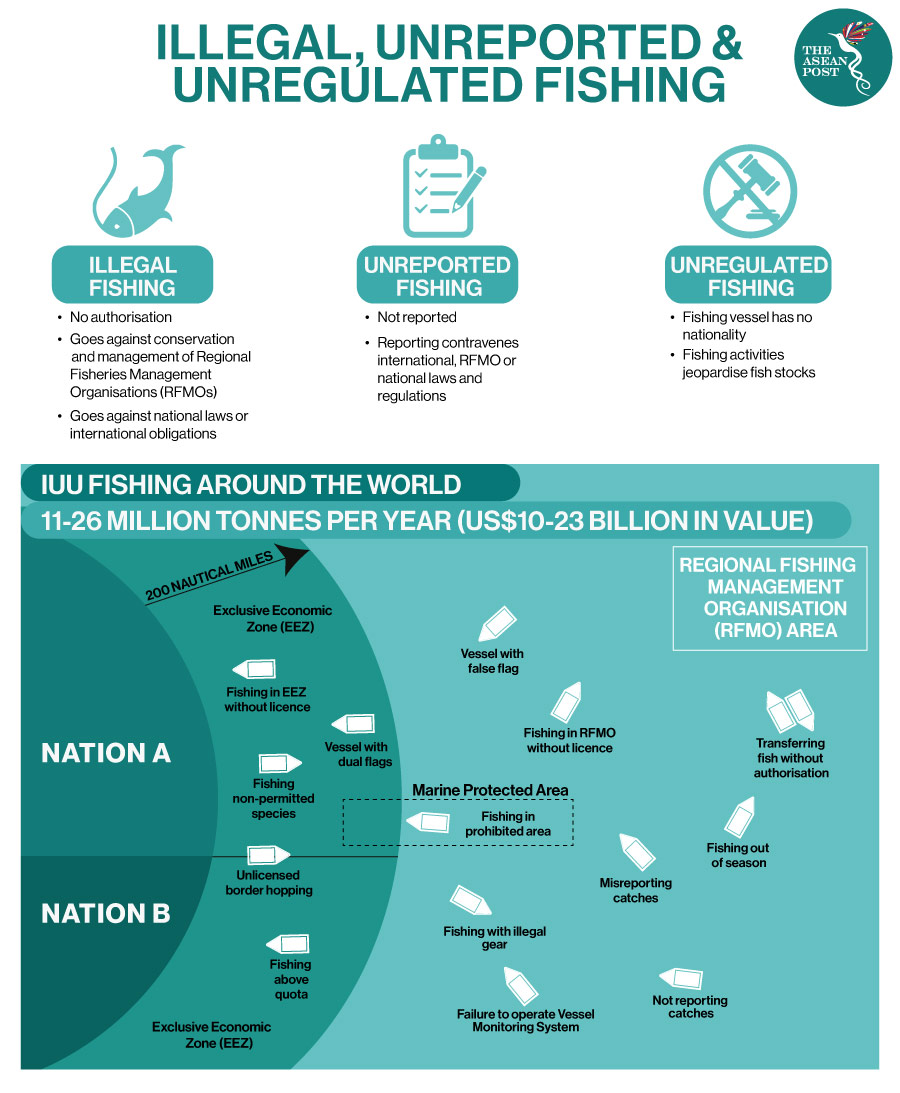

The failure of Vietnam’s efforts to remove the yellow card should be ascribed to Vietnam’s limited progress in improving fisheries governance and curbing IUU fishing. In other words, Vietnam has not effectively enacted all recommendations raised by the EC, including: (1) Revising the legal framework to ensure compliance with international and regional rules applicable to the conservation and management of fisheries resources; (2) Ensuring effective implementation and enforcement of country’s revised laws; (3) Strengthening the effective implementation of international rules and management measures; (4) Increasing the traceability of its seafood products; and (5) Preventing sales of IUU products.

Nevertheless, as Vietnamese officials have repeatedly stated, the government of Vietnam has taken strict measures and made significant progress in recent years to fulfil the EC’s requirements, such as (1) Amending the fisheries law and strengthening legislation; (2) Creating a legal framework for a gradual transition to commercial, responsible and sustainable fisheries; (3) Reducing the number of Vietnamese fishing boats operating illegally in other countries; (4) Downsizing the fishing fleet; and (5) Strengthening education and information so as to raise awareness among fishermen not to violate other countries’ waters.

But why is there such a big gap between Vietnam’s intentions and reality? A direct answer is that the effectiveness of Vietnam’s implementation of the relevant policies to curb IUU fishing is far from expected. This begs the subsequent questions: What has caused the ineffectiveness? What is the most reasonable resolution to improve efficiency?

Factors For Failure

From an economic perspective, Vietnam has suffered vast losses because of the yellow card status and has a strong need to remove it. Recent statistics show that Vietnam’s export of fishery products relied considerably on the European (EU) market, which is one of the biggest export markets for its fishery products. Vietnam’s seafood exports were valued at US$1.3 billion in 2019, accounting for 15.1 percent of its total seafood exports.

The EU is a market with many strict technical regulations on food safety, environment and sustainable development. Vietnamese businesses should meet the requirements of food safety and hygiene to access this lucrative market, especially since the formal enactment of the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA).

Quality is paramount and key to Vietnam’s development strategy for seafood exports. Due to the yellow card for Vietnam's seafood products, its exports to the EU fell by 6.5 percent to US$390 million in 2018 and by 11.5 percent to US$345.2 million in 2019 according to its Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD).

However, such economic concerns have not resulted in a strong impetus for being fully committed to curbing IUU fishing. The reasons are multi-faceted.

First, fishing operations by Vietnamese fishermen and fishing boats, either legal or illegal have been regarded as a necessary means by the government to safeguard its maritime rights. As such, the Vietnamese government hesitates to exert all efforts to regulate fishing activities, despite evoking strong protests from neighbouring countries because of encroachment of Vietnamese fishing boats into overlapping waters.

Second, exhausting fishery resources, an unsuccessful fishery industrial transition and upgrading has resulted in limited employment opportunities for local fishermen, who are forced to take the risk of conducting illegal fishing activities for survival.

Third, the regulatory authorities sometimes lack the ability to monitor IUU fishing due to financial and technological factors.

Rescinding The Card: New Perspectives Needed

In short, Vietnam’s battle with IUU fishing lacks motivation, either politically or socio-economically. Facing past unsuccessful experiences and current pressures, Vietnam must adopt new thinking.

First, relevant policies need to start with multi- and bilateral cooperation rather than unilateral activities. Illegal fishing activities have long been a source of contention in regional disputes and flare-ups between regional states. Curbing IUU fishing hence cannot be conducted unilaterally.

One precondition for effective cooperation with neighbouring countries is to maintain the stability at sea. It is thus important for Vietnam to abandon the idea that encroaching into disputed waters by Vietnamese fishermen is a means of safeguarding its maritime sovereignty. Maritime disputes can only be solved through negotiation under international laws such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

In this regard, jointly supporting the establishment of an IUU fishing combat network is in the interest of all states around the South China Sea. Otherwise, it would be difficult to effectively deal with the illegal activities of Vietnam’s fishing vessels.

Second, pursuing innovative approaches in improving the living standards of fishermen is essential for reducing their dependence on illegal fishing. Currently more than half of Southeast Asia’s inhabitants rely on fisheries and aquaculture for their livelihoods and the same can be said for Vietnam.

Due to the constantly exhausted fishery resources, it is understandable that local fishermen will continue using illegal methods to increase their catch. Policy-makers have to consider how to diversify their income sources. Deep-sea farming and aquaculture should be encouraged. Advanced processing industries can be established to upgrade the export structure with value-added fishery and seafood products aimed at the EU market.

Third, introducing high technology to optimise existing monitoring systems is essential in tracing IUU fishing. Although Vietnam has made great efforts in installing fishing vessel monitoring systems based on the EC’s recommendations, only about 30 percent of all Vietnamese fishing boats have been equipped with such facilities.

Moreover, future IUU fishing trace and suppression need the Vietnamese government to apply high-tech facilities and infrastructure, such as an IT-driven risk management system, big-data analysis, wireless sensor networks, etc. This requires the Vietnamese government to allocate more funds and resources for research and development. In this regard, jointly developing an advanced and shared monitoring system by regional states would be more cost-efficient.

Of course, all parties should bear in mind that curbing IUU fishing is a time- and resource-consuming process. Some scholars have argued that regional states’ efforts to combat IUU fishing are seldom fully evaluated. Some research institutions also emphasise too much on the status quo, reducing the interest of the EC and other countries in making positive progress in practice.

Nevertheless, to remove the yellow card, Vietnam has to insist on co-operation, transparency and honesty in providing and exchanging information regarding curbing IUU fishing. Only in this way can Vietnam harvest the benefits of extensive environmental, economic and diplomatic benefits.

Related Articles: