According to the World Bank’s latest economic update on Cambodia, the country’s economy this year will contract by -1 and -2.9 percent. This is a worrying sign given the kingdom’s reliance on tourism, manufacturing exports, agriculture and construction. In realising this fact, Australia has stepped up its efforts to help reduce the impact on Cambodian citizens, while also responding to its own economic issues.

As strategic partners, this gesture is a sign of close cooperation and close ties between Cambodia and Australia. It also shows that Australia cares for the well-being of Cambodians and is ready to build institutions that are capable of weathering economic crises.

Diversified Laissez-Fair Market Economy

Poverty could increase among households involved in industries that are key economic drivers of growth in Cambodia this year. According to the World Bank, the fiscal deficit projection could reach its highest level in 22 years and could put almost 1.76 million Cambodian jobs at risk. This could cause a severe slowdown in the construction and garment manufacturing sectors due to supply chain stagnation from China and Vietnam.

The fallout can be undone; however, through wise leadership which provides economic relief and public health protections – easing the pain short term, and also through fostering macroeconomic stability in the long term via fiscal policy measures.

If Cambodia can withstand a 12-year economic embargo from many nations since 1979, then this crisis can serve as another testing point for the ASEAN member state.

The government has been at the forefront in preparing a stimulus package for citizens hit hardest by the crisis. Revenues from customs and taxation, as well as billions in aid are pouring in from abroad. But more needs to be done in terms of diversification. Cambodia should further encourage the diversification of its economy so that it is not just reliant on a select number of industries for economic growth and employment of its youth.

Learning From The Past And Neighbours

The possibility of Cambodia being used as a geopolitical proxy platform is growing as tensions between China and the United States (US), as well as China and Vietnam escalate. As New Cold War posturing starts to surface between superpowers on the global stage, Cambodia simply cannot afford to get stuck in another warzone again due to its geopolitical location – trapped between two major economic and political powerhouses. The risks and costs are too high to bear for a nation that is still on the road to recovery.

In responding to this, Cambodia should first look to Thailand for a glimpse of hope and inspiration. Thailand has never been colonised and has always been a ground for healthy competition that has been beneficial, economically and politically. Through an aggressive Teflon approach, Thailand has continued to attract foreign investments despite political turbulence; transforming itself from an agrarian-based economy to a modern industrial powerhouse.

Secondly, Cambodia should open its ports and trading routes to all major international players once again after the global pandemic is over. The country is well positioned at the centre of commercial activity, with major routes crossing Cambodia’s waters and ports such as Sihanoukville on the Gulf of Siam, the Phnom Penh Autonomous Port, and the provincial port of Koh Kong.

These ports cut across the Mekong River and goods and supplies can be easily dispersed to major economies such as Singapore, Japan, Vietnam, Thailand, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, India and Malaysia. Although, seeing a stark decrease in profits, it is without a doubt that once the pandemic is over, more traffic will flow through these seaports as economic activity in China starts to pick up.

Lastly, Cambodia’s stance and approach to foreign policy should be consistent. Cambodia must continue to remain neutral on territorial issues and urge all parties with vested interests to deal with the issue peacefully, without the use of threats or coercion.

Re-Energize Political Culture

This policy proposal is simple, yet powerful. It is for all Cambodian citizens to unite and reconciliate, upholding the very principles stated in the Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia.

The country needs to reset its political agenda and culture if it wants to enjoy political stability. A majority of Cambodia’s population is made of young people under the age of 35 who want to move forward.

As the saying goes, we need to learn to agree to disagree, and develop mutual respect, understanding, and have an open mind without bias on the basis of racial background, religious affiliation, and socioeconomic status.

If Cambodians have a genuine desire to rebuild the country, imagine what the country will be able to accomplish in the future. To that end, Cambodia should forge its own style of democracy, one that is firmly grounded in Nation, Religion, and King.

Quality Education

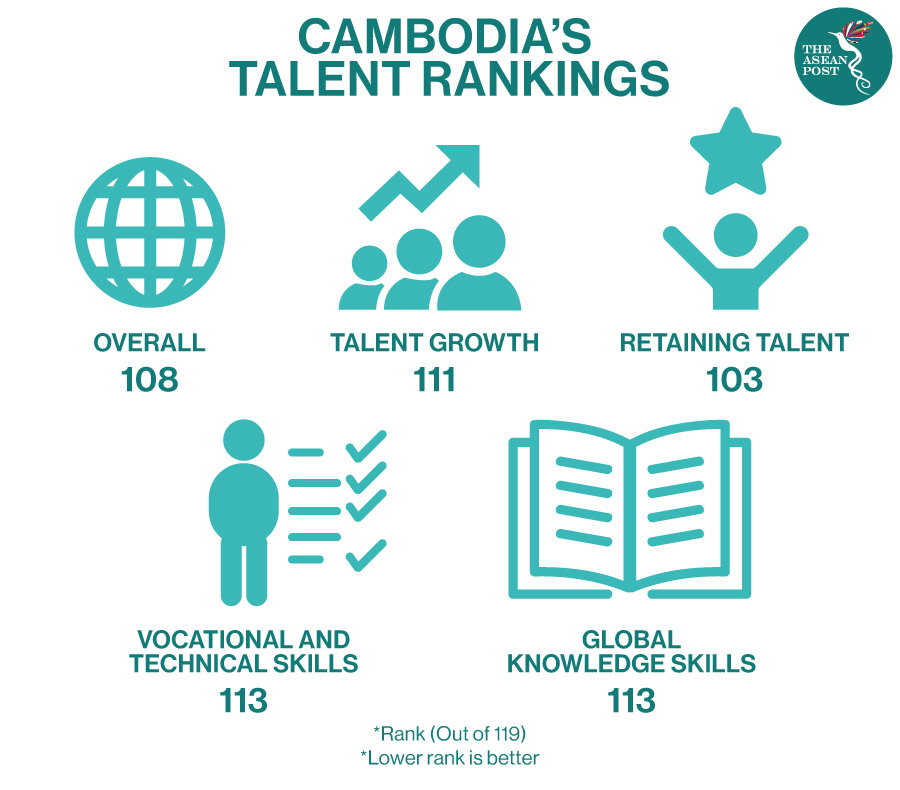

The key to rebuilding a nation is its people. Special focus must be paid to the importance of quality education in Cambodia. It is key for human development and sustainable growth. On one hand, Cambodia can rejoice knowing that spending on education and teachers’ salaries tripled from US$343 million in 2014 to US$848 million in 2018. On the other hand, the inequality and lack of quality education in public schools remains a big challenge.

The policy solution is straightforward. By strengthening accountability and transparency in public schools, we can start to see a correlation between quality of teachers and increase in salaries as well as academic performance. As a result, the literacy rate and STEM scores will increase among young children and teens between grades seven to 12.

Related Articles: