Several structural shifts have left ASEAN more exposed to an economic downturn than during the last global financial crisis a decade ago.

While ASEAN did not technically slide into recession during the last global financial crisis, structural traits that cushioned the region a decade ago – such as China’s strong growth and the global demand for commodities – now offer less of a buffer noted a report by global consultancy firm Bain & Co. last week.

“The region’s strong economic growth does not, in fact, shelter it from harm should other parts of the world sink into a downturn or even a recession. Individual companies and even entire industries could feel deeper pain based on their exposure to other regions, sectors or commodity prices,” warned the report titled ‘A Downturn Favours the Prepared, Even for Southeast Asian Companies’.

In a sign of the impeding economic downturn, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) announced last week that global economic growth has decelerated to the slowest pace since the 2008 financial crisis due to trade conflicts and increased policy uncertainty, with OECD chief economist Laurence Boone saying that the global economy is facing increasingly serious headwinds and slow growth is becoming “worryingly entrenched.”

Lower growth rates, poorer current account balances

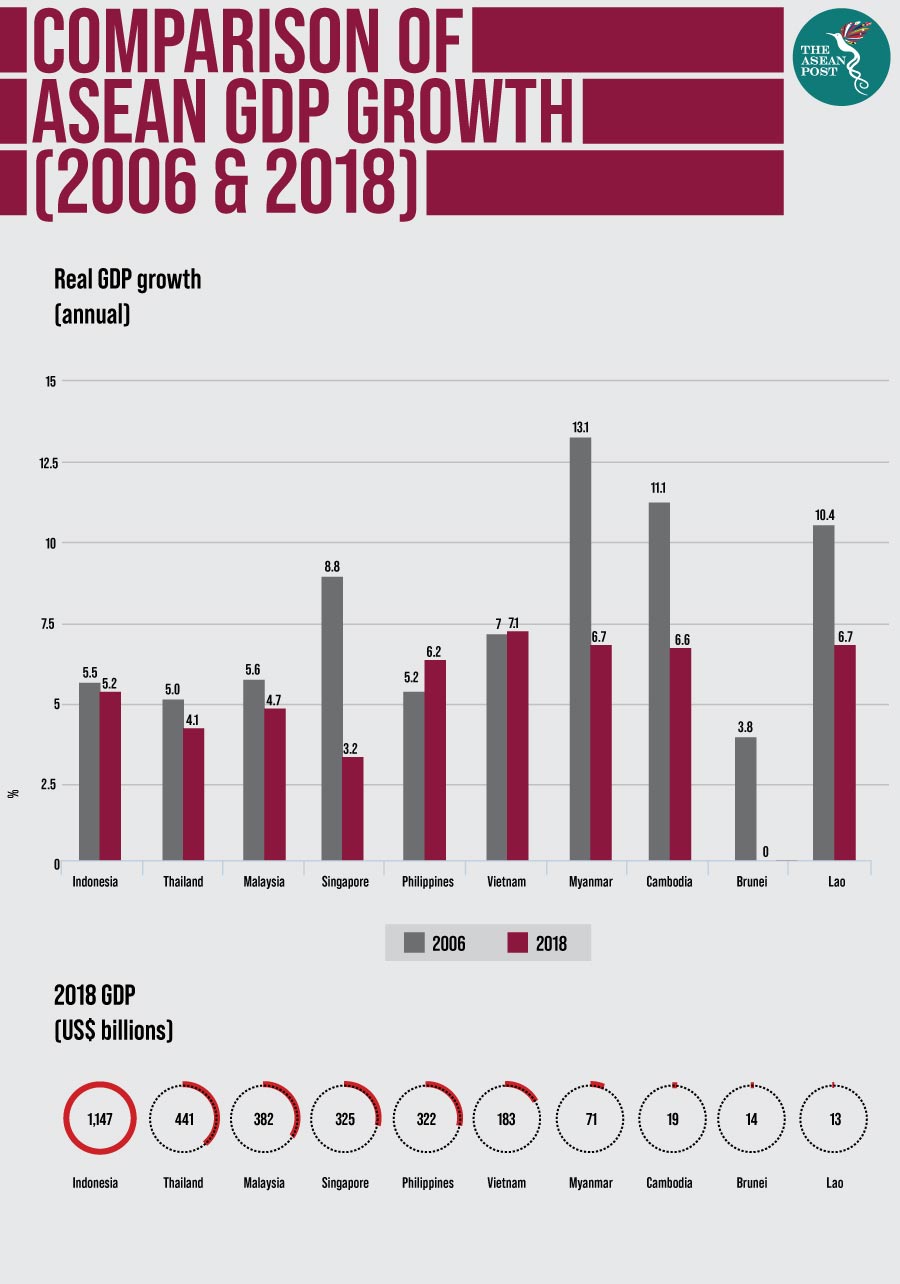

ASEAN growth rates are lower for eight of the 10 ASEAN nations than they were during the last global financial crisis, with only the Philippines and Vietnam bucking this trend. This lower starting point is a concern as it increases the risk of countries getting closer to a technical recession – or two consecutive quarters of economic contraction.

In its ‘Economic Update: South-East Asia’ report released last week, the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) predicted that economic growth across the region is expected to moderate to 4.5 percent in 2019 from 5.1 percent in 2018 amid another round of tariffs and trade restrictions by the United States (US) and China.

As Mark Billington, ICAEW’s Regional Director (Greater China and Southeast Asia) noted, challenging external conditions are expected to continue weighing heavily on the overall growth across the region’s economies and trade flows.

In addition, ASEAN’s current account balances (a country’s net income over a period of time) have also dropped since the last global financial crisis, shifting five of the 10 countries into a deficit as exports declined as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) – increasing reliance on capital inflows.

ASEAN’s largest economy, Indonesia’s current account deficit was US$8.4 billion – equal to 3.4 percent of GDP – in the second quarter of this year, higher than the US$7billion recorded over the same period last year.

The China factor

With its strong trade and financial linkages, ASEAN is also heavily dependent on exports to other countries – most notably the US, the European Union (EU) – which is worried about a no-deal Brexit scenario – and China.

China has been ASEAN’s largest trading partner for the past nine years, and in the first half of this year, ASEAN became China’s second-largest trading partner – behind only the EU – and overtaking the US for the first time since 1997.

However, with China’s GDP growth easing from 12.7 percent in 2006 to 6.6 percent in 2018 according to the Economist Intelligence Unit, this increased exposure to China’s economy is putting ASEAN at greater risk from a Chinese slowdown – especially with the US-China trade war still in full swing.

ASEAN’s third largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI), this reliance on China was heightened on Sunday when the Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) said it will invest in six projects worth US$1.09 billion in ASEAN as its president, Jin Liqun, played up the role of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in boosting connectivity in the region.

A multilateral development bank which focuses on infrastructure investment, the AIIB began operations in 2016 and has approved 46 loan projects worth US$8.5 billion – with US$1 billion channelled to 10 projects in Southeast Asia over the past four years.

Commodities and debt

Commodities’ contribution to the region’s GDP has dropped from 23 percent to 18 percent, and with prices and sales both on a downward trend, it is unlikely the sector will be able to cushion the economic blow of an ASEAN recession.

As the Bain & Co. report notes, the shape of a downturn throughout the region could vary depending on the severity and causes of a global recession in countries that buy large amounts of ASEAN’s palm oil, coal, computers and other goods.

Meanwhile, corporate and household debt have risen significantly as a share of GDP in Southeast Asia — in many cases exceeding 2008 and 2009 levels and closing in on levels seen in developed markets such as the US.

While countries across the region will each have their own policies to combat the looming recession, a more economically integrated ASEAN is better prepared to weather the storm and rely on one another for trade and investment growth.

Related articles:

Is Malaysia heading for a recession?