The dangers of corporations owning large amounts of personal data have been heavily debated in recent years with no real solution to the issue.

Data has been branded the new currency in the world. For years, users of online platforms did not realise that they were “paying” for “free” online services such as Facebook and Google with their personal data.

The data obtained was used to analyse and segregate users according to personality traits, behaviour and interests to name a few.

In 2018, a major scandal broke when it was found that Facebook had illegally sold personal data of up to 87 million of its users to a former British political consulting firm, Cambridge Analytica. The data was acquired from 270,000 Facebook users who used a Facebook app called "This Is Your Digital Life."

The data was then used to target American voters on the fence – those who hadn’t decided which political party to support – by amplifying right-wing propaganda through advertising to sway voters. The same method was also used during the Brexit campaign.

A Netflix documentary 'The Great Hack' exposed some of the practices by both, Facebook and Cambridge Analytica and found that this method of political persuasion was tested by Facebook in countries such as Kenya, India, Malaysia and Mexico before it was used in the United States (US) and United Kingdom (UK).

The controversy raised some serious questions as to how personal data is used by international corporations and to what extent. For instance, how much of our behaviour is predictable by advertising teams whose task is to influence our decisions?

The European Union (EU) quickly acted on this security threat by enacting a data protection legal framework. The EU General Data Protection Regulation ensures that personal data can only be gathered under strict conditions and for legitimate purposes.

Personal data exploited

Asian countries have benefitted from this as the internet giants located in the US and the EU have to comply with the regulations and serve their international users with the same respect.

But what happens when governments use this controversy to create policies that exploit our personal data?

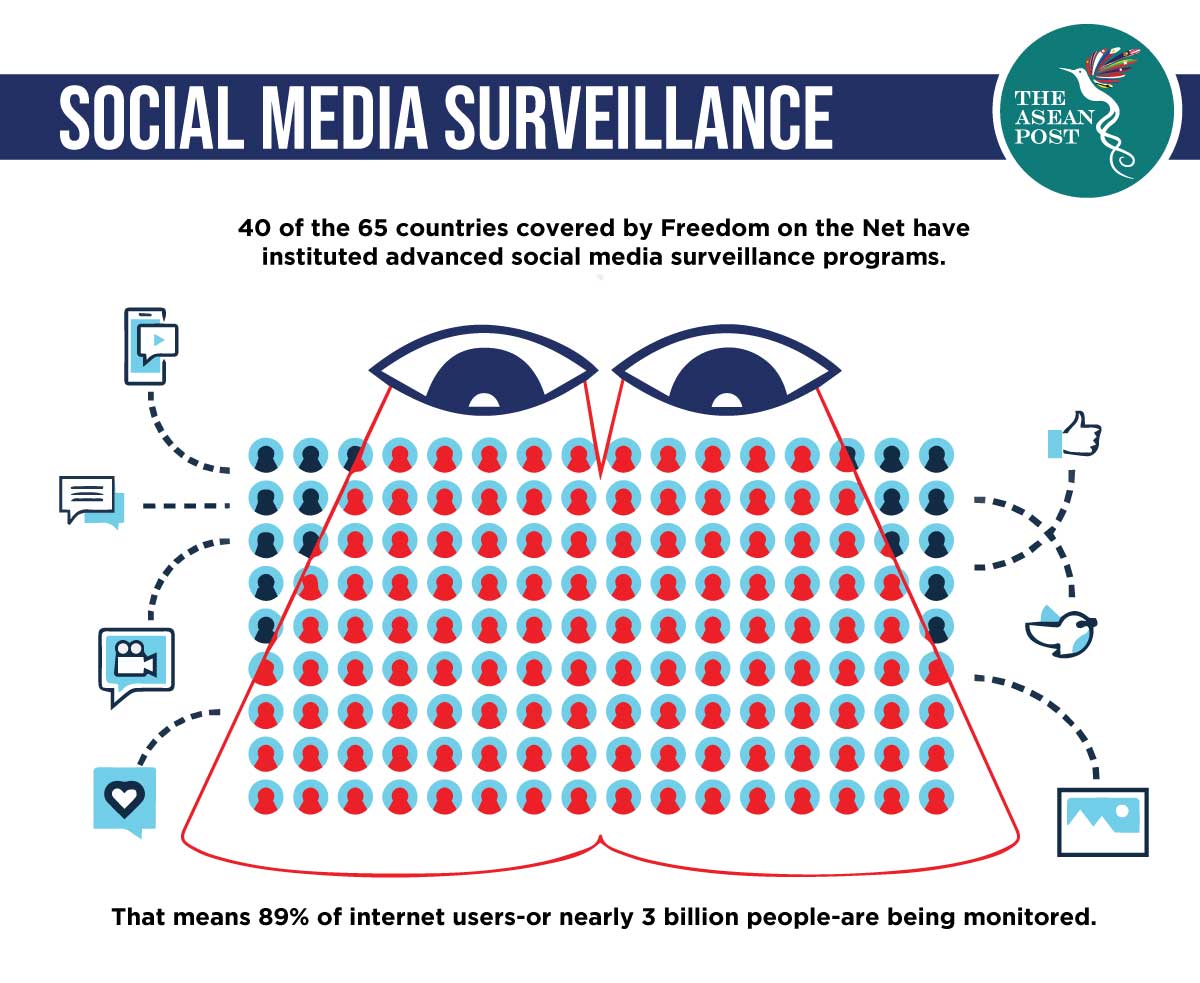

According to a report by international watchdog organisation, Freedom House, governments are demanding that private companies share their citizens’ personal data as a way of monitoring how companies' use the data obtained.

The report indicated that countries like China, Russia, Vietnam and Pakistan have already enforced laws that give their governments direct access to personal data that users had initially given to corporations in their respective countries. In some of these countries, users are unaware that their personal data is also accessible by their government.

"The risks of governments having this information is that a lot of the countries that want access to this data do not have the best reputation at protecting fundamental freedom and human rights," Allie Funk, research analyst at Freedom House told The ASEAN Post. "They could actually use it to access what citizens are saying on social media or WhatsApp – to then go target that person."

She proceeded to explain that some countries with certain ideologies could pick up keywords in conversations that would indicate an individual’s religious beliefs or pick up on activists and human rights defenders talking about strategizing against a certain policy that could lead to criticism of the government. Access to this information would allow a government to more easily target a user by labelling them a ‘security threat’ with enough justification for an arrest or detention.

Governments are able to do this by using data localisation laws which require corporations to store personal data of users from their countries on a local server. It is no surprise that more governments are interested in this policy.

For example, in a country like Russia, it would make it easier for the government there to access a citizen’s information legally through a local server rather than request it from an international corporation whose server is located in another country. In a situation where personal data of a citizen is stored on a server located abroad, proper justification must be given in order for the exchange of information to be legal. Therefore, localisation of data makes for a more convenient alternative.

This should be a major concern for Southeast Asians. While citizens from democratic countries in the EU or those in Nordic countries have significant legal power to challenge these policies, citizens of countries with a weaker democratic index cannot rely on institutions that do not uphold international human rights standards.

Related articles: