China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was intended to empower developing countries with improved infrastructure and trade relations. In the five years since it was mooted, the BRI is now being demonised as a debt-trap that ensnares poor nations into subservience to China. Another unintended consequence is its alleged connection to corruption.

Infrastructure projects are notoriously vulnerable to corruption, featuring inflated costs and kickbacks. According to Will Doig in his book, High-Speed Empire, local politicians often have opportunistic motivations to approve BRI projects. They can claim credit for bringing development to their constituents while getting kickbacks for themselves.

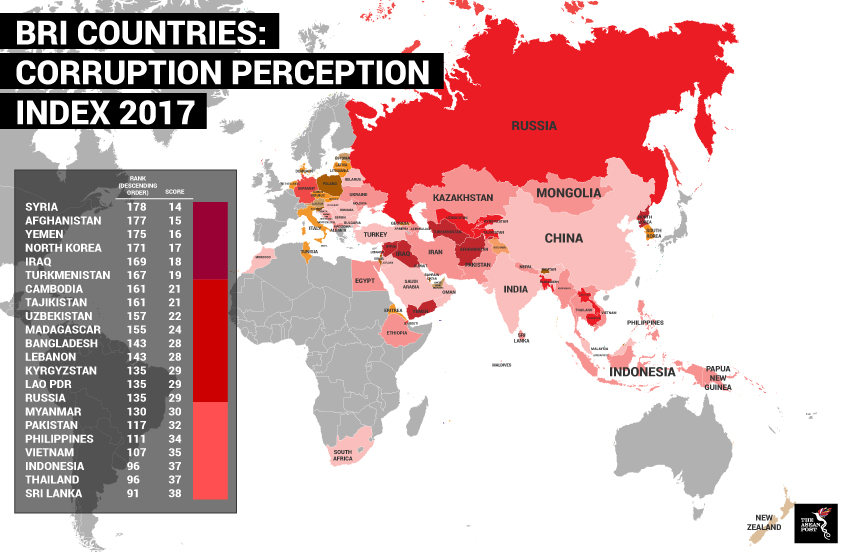

Interestingly, a large number of BRI-linked countries rank high on the global corruption perception index. This increases the likelihood of corruption when massive funds come to town.

In Kyrgyzstan, government officials there were accused of colluding with Chinese contractors to embezzle BRI funds by grossly overpricing project costs. Two former prime ministers were arrested on corruption charges.

Allegations of corruption in BRI-related projects have even caused the downfall of several governments. Sri Lanka’s President Mahinda Rajapaksa was ousted in 2015 elections. Malaysia’s decades-long rule by the National Front coalition was ended this year. Likewise, the incumbent party lost in Pakistan’s elections. Most recently, Maldives’ authoritarian President Abdulla Yameen lost in the country’s presidential election.

Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port was a vanity project mooted by its then-President Mahinda Rajapaksa. The island state was internationally isolated following a brutal military crackdown on separatist Tamil Tigers. Rajapaksa approached China for loans when he could not get the funding he needed.

International media reported that large amounts of money allegedly flowed from the Chinese’s port construction fund to Rajapaksa’s election campaign. He still lost.

Not the only guilty party

Part of the debt-trap narrative is how China “insidiously” inflates prices for the projects to get its victims in deep debt in order to extract resources and territories.

Yet, officials in these countries could be the actors behind the inflated costs and opaque deals. Chinese companies should shoulder some of the blame as enablers. However, they are no different from other foreign companies operating in countries with corrupt regimes. Kickbacks are usually part of the cost of doing business.

The onerous terms of the loans could very well be due to the high risks involved. It is likely that other development banks would not have agreed to such terms.

Pakistan’s previous government alluded to this when it allegedly tried to blackmail China to continue lending it money. It threatened to reveal terms of their agreements should it be forced to approach the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout. They claimed the IMF would probably conclude the deals should not have been made.

Malaysia’s new government chaffed at the one-sided BRI deals signed by the previous administration and has cancelled several projects. “Such stupidity has never been seen before in the history of Malaysia,” remarked Malaysia’s Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohamad.

Source: Transparency International

Source: Transparency International

China has an extremely low tolerance for corruption domestically. Those found guilty are usually executed. However, it is surprisingly sanguine when it comes to corruption in foreign countries it deals with. This could be explained in a comment by China’s ambassador to Kyrgyzstan on its corruption case, “The investigation is an internal affair of Kyrgyzstan and we do not interfere.”

Non-interference has been a hallmark in China’s international policy, just as much as it wants foreign countries to stay out of its internal affairs, especially with regards to human rights violations.

Western critics of the BRI often cherry-pick their cases to highlight the initiative’s failings. They conveniently fail to recognise that the partner countries are as much to blame for placing themselves in financially unviable positions.

Sri Lanka’s Rajapaksa willingly borrowed increasing amounts of money from China in exchange for whatever the latter asked for. Not satisfied with having an under-utilised port, he built a new – and also under-utilised – International airport nearby.

Pakistan had wanted to develop an economic corridor with China and construct major highways, and China happens to want the same thing and has money to spare. Pakistan’s financial woes are not necessarily caused by the BRI. In 2017, its debt servicing totalled US$5 billion with only 10 percent going to China; some 60 percent of foreign loans were owed to multilateral foreign institutions and members of the Paris Club, a forum of debtor nations.

Pakistan had similar payments crises in 2000, 2008 and 2013, which coincided with changes of government. Incumbent governments tend to postpone spending until they near the end of their terms and then spend heavily before the elections to gain more votes.

Myanmar scaled down its new port in Kyauk Pyu from US$7.3 billion to US$1.3 billion by reducing the scale of construction set by previous administrators.

Belt tightening

With the BRI linked to his name, Chinese President Xi Jinping is likely keen to dispel the negative image associated with it. At the June 2017 Belt and Road Forum, he called on countries to “strengthen international counter-corruption coordination” so that the BRI will be a “road with high ethical standards.”

In December 2017, China temporarily halted funding for at least three major road projects linked to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) following reports of corruption. Nepal’s US$2.5 billion Budhi Gandaki hydropower project was also cancelled due to irregularities in the bidding phase.

China is also tightening its belt on funds. Far fewer deals have been signed this year. In April, Yi Gang, the new governor of China’s central bank said at a conference, “Ensuring debt sustainability – that is very important.”

In the Global Anticorruption Blog, lawyer Edmund Bao proposed the creation of a “Silk Road Anti-Corruption Body” that would have four primary functions. First, it should authorise and coordinate investigations. Second, it should coordinate financial regulation to deter money laundering, embezzlement and false accounting, among others. Third, it should produce best practice guidelines for ethical business transactions. Finally, it should advocate and facilitate incorporating anti-corruption provisions in future agreements.

Related articles:

BRI debt trap: An unintended consequence?