Providing accessibility for the disabled is a major determinant for developing countries to qualify as developed nations. Most ASEAN countries apart from Singapore, struggle to provide basic structures for accessibility in public buildings, schools, transportation, and even tourist spots.

While small steps are being made across the continent to improve access, much of Asia remains inaccessible to wheelchair users, who face a multitude of issues navigating cities, finding accommodation and accessing attractions.

The underdevelopment of these facilities has been internationally highlighted by tourists travelling from Western countries, complaining that they do not have the freedom to explore attractions in Southeast Asia as they lack wheelchair-friendly options.

Accessibility is just one of the many factors that pose a significant barrier for disabled people in society. Nonetheless, the physical environment is a crucial part of the infrastructure that would allow development in other areas such as access to education, employment, entertainment and other facilities that able-bodied people have direct access to.

In Cambodia, the Phnom Penh Centre For Independent Living, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) with the mission to empower people with severe disabilities to live independently, reported that the physical environment in Cambodia contains multiple obstacles – where public streets and roadways have no facilities for persons with disabilities, and getting around is dangerous at best – in many cases almost impossible.

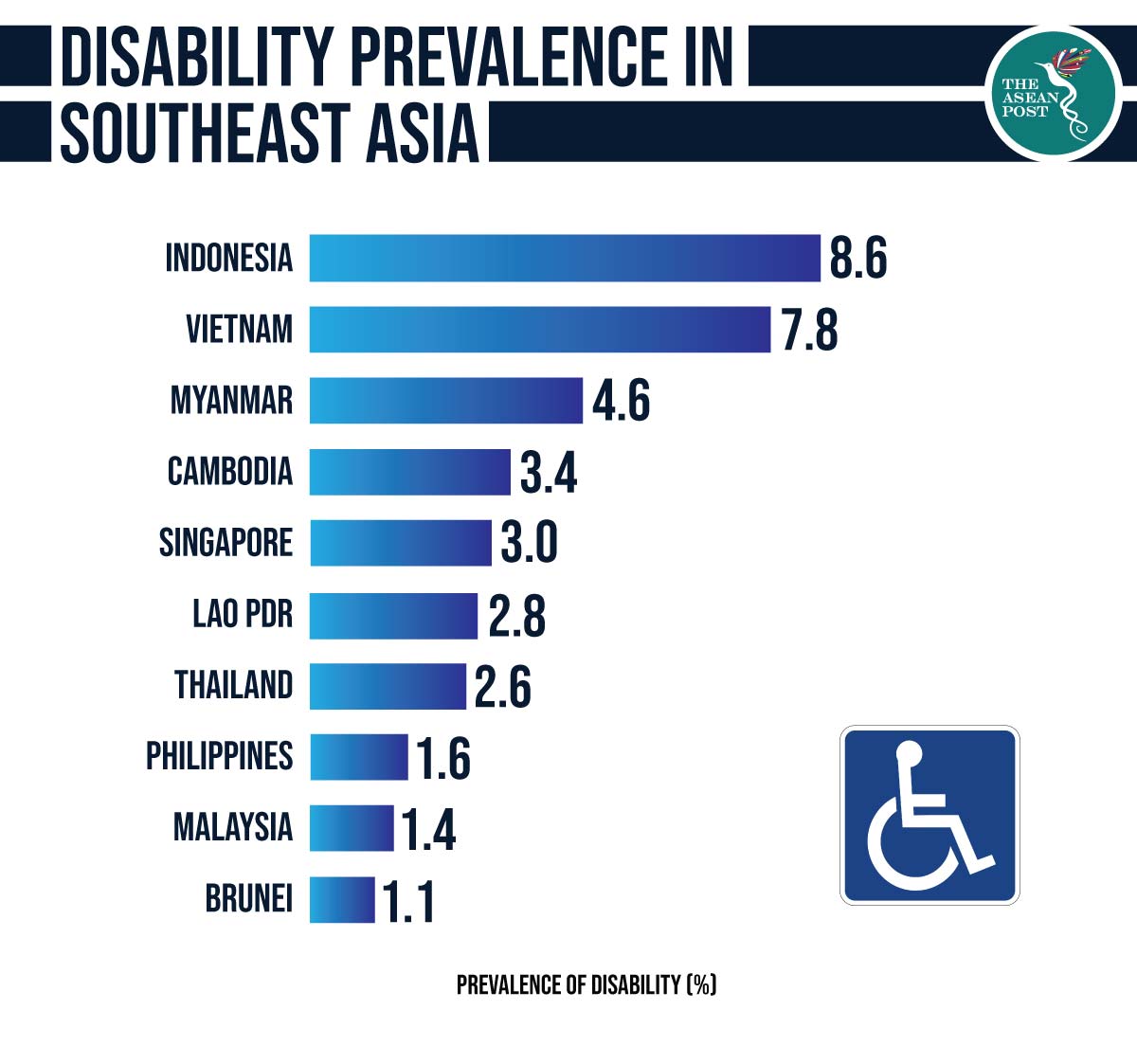

While the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that 15 percent of the global population lives with disabilities, data on disabled Cambodians vary from eight percent of the population in 2009 to two percent in 2015. It is safe to say that inconsistent data collection methods reflect the poor understanding of disability that stems from various reasons.

A study in 2016 by the University of Melbourne found that less than four percent of disabled Cambodians receive any form of financial assistance from the government even though Cambodia passed a sub-decree in 2011 entitling citizens living with severe functional impairments to a monthly pension.

At a workshop organised by the Disability Action Council to develop Cambodia’s National Disability Strategic Plan, Cheat Sokha, a participant who suffered a serious spinal injury following an artillery explosion in 1985, told local media that disabled people in Cambodia continue to receive fewer opportunities in education and at the workplace.

“People with disabilities receive less attention and encouragement from family and society. As a consequence, they lose the chance to receive an education or skills to improve their quality of life," explained Sokha. "Schools and educational institutions do not currently make proper allowances to accommodate disabled people either."

Stronger action plans in order to develop infrastructure that meets the needs of the disabled in Cambodia is urgently needed, especially for those in rural villages that are unable to leave their houses to earn a living, who are forced to stay at home and remain in constant need of assistance.

“From day to day, I feel too shy and become lonely because of my disability, and sometimes come to think that I can’t do anything for my life. I couldn’t see a bright future, and I became very depressed. The most worrying is how I can live without my mother because she always helps me. What will happen when Mom goes away from me?” said 27-year-old Poeng Haseka, who is currently undergoing training at the Phnom Penh Centre For Independent Living.

Related articles: