Indonesia’s National Police recently announced that it would increase the allowances of police officers by 70 percent. According to police chief General Tito Karnavian, the allowances would apply retroactively and would be paid out this month.

Tito expressed confidence that the increase would not only boost the police officers’ performance but may also contribute towards efforts to reform the institution and reduce corruption.

Meanwhile, Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati has also revealed that she is mulling increasing the salaries of regional leaders, following the spate of governors and regents arrested for graft by the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) in the past. As of October 2018, 25 regional leaders have been investigated.

“We are conducting a study. We will also convey the idea to the president, because he also has concerns about remuneration arrangements, particularly for officials in the regions,” she said.

The two separate statements act as kindling to a question that has been debated by many analysts and observers: “Is giving more money indeed an effective means of eradicating corruption among civil servants?”

Struggling with corruption

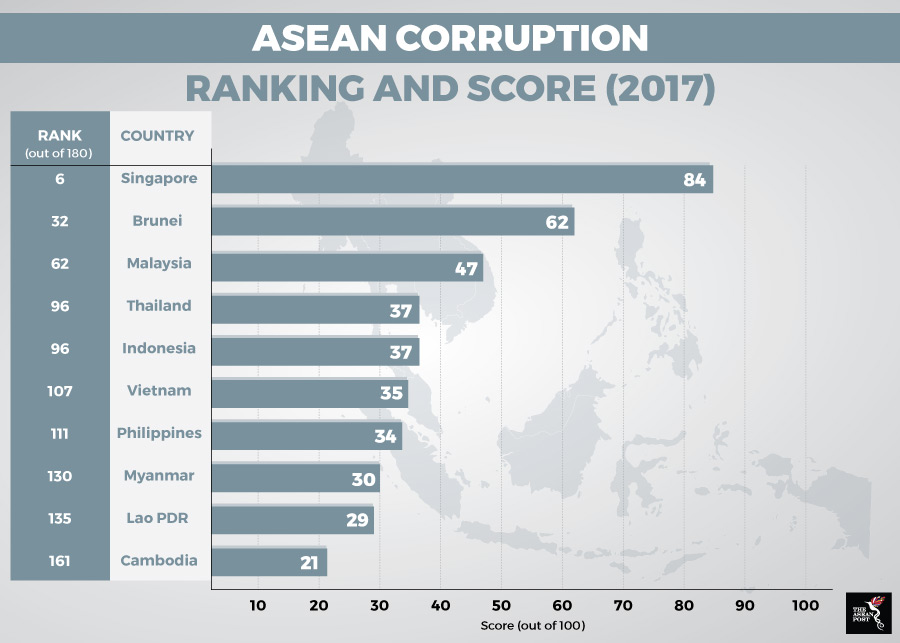

Transparency International’s 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index places Indonesia in 96th spot out of 180 countries with a score of 37 out of 100. The results of the 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index has yet to be released.

In fact, the number of cases being investigated by the KPK has been increasing steadily between 2008 and 2017. In 2017, there were 118 cases under investigation compared to 2008 where there were just 47.

Other institutions are seeing even higher numbers. The National Police are currently investigating 1,028 cases while the Attorney-General’s Office is investigating 1,552.

Source: Transparency International

Source: Transparency International

As for the KPK, civil servants made up the largest number of those being investigated for corruption between 2004 and 2018, making up 26 percent of the total number of cases. Moreover, Transparency International’s 2017 Global Corruption Barometer, which polled more than 1,000 respondents in 31 provinces across the country, found that half of the respondents considered civil servants the most graft-ridden individuals.

In commenting on Indonesia’s corruption and whether paying civil servants more would help curb it, Transparency International’s Indonesia secretary-general Dadang Trisasongko claimed that while increasing salaries could help reduce petty corruption among low-level police officers and other civil servants, it would do little to address bigger graft cases.

“We can see cases of corruption among police that involve very large amounts of money, which shows that an increase in salaries or benefits won’t have much of an effect in preventing graft. That level of corruption is perpetrated to maintain a lavish lifestyle. Regular oversight of civil servants’ wealth would be more effective in preventing that type of graft,” he said.

Does money curb corruption?

When talking about the correlation between more pay and less corruption, two case studies provide important insight.

The first is an ongoing policy experiment conducted by researchers from the United States (US); Kweku Opoku-Agyemang from the Blum Center for Developing Economies, University of California, Berkeley; and Jeremy D. Foltz from the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

The experiment was conducted on highways in Ghana involving policemen and the truck drivers who would bribe them. The results found that not only did the police spend more time shaking down drivers after they received higher salaries, but they took significantly more money after receiving higher wages.

“Instead of leading to a more (if the reader would permit us) civil police force, the higher salaries seemed to give them a higher appetite for corruption,” Opoku-Agyemang wrote.

Another study conducted by Alfred M Wu from the National University of Singapore and Ting Gong from the City University of Hong Kong tells of another insightful story.

According to their research which looked at the civil service in China, the effect of civil service pay raises on deterring corruption was tenuous and, hence, relying on salary increases as an anti-corruption strategy is “far from adequate”.

They did, however, note that low civil service remuneration, especially in less developed nations, is often believed to be an important contributing factor to corruption as it erodes employee incentives, whereas higher salaries raise the stakes of engaging in corruption, as corrupt officials risk losing more if caught.

“We argue that the relationship between civil service pay and corruption should be treated with caution. As our findings indicate, civil service pay in China has steadily and substantially increased in the past decade. The scope and magnitude of each increment were large and significant enough to indicate a fundamental change to the long-existing ‘low wage and low consumption’ policy that had dominated pre-reform China,” they wrote.

“Salary rates of government employees have increased not only in absolute terms but also in relation to other social groups. At the same time, however, corruption in the country remains uncontrolled.”

As the two studies have shown, it is highly unlikely that bumping up a few salaries or giving better allowances will result in a significant drop in Indonesia’s corruption statistics. More than likely, the government there will need to look at a more holistic approach which not only involves those in employment but the nation as a whole.

Related articles:

Indonesia’s disenchanted youth