Soon after November rolled in, reports surfaced of a bet between Cambodian prime minister Hun Sen and Cambodian National Rescue Movement (CNRM) leader Sam Rainsy on the fate of former Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) leader Kem Sokha, who is on bail awaiting trial on treason charges. Rainsy, who is under self-imposed exile, initiated the bet; saying that the former Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) leader would be released from “house arrest” between 29 December and 3 March next year.

“I believe that under international pressure, Hun Sen would be forced to release Kem Sokha soon. It could be [between] 29 December, 2018, or 3 March, 2019, at the latest.

“If Mr Hun Sen loses the bet with me…I am asking him to step down, but if I lose, I will walk into jail and be detained with Kem Sokha,” Rainsy said.

Hun Sen accepted.

Observers have surmised that the bet was made in a bid to show just how much power Hun Sen - a democratically elected prime minister (depending on who you ask) – holds in his country. Rainsy’s assertion seems to be that even the judiciary is under Hun Sen’s thumb and that Sokha’s arrest was politically motivated in the first place.

On the other hand, Hun Sen, has insisted that he does not have the power to release Sokha even if he wanted to, adding that he had no intention of violating the court’s jurisdiction.

“The prime minister has no right to request for a pardon for someone who has yet to be convicted. According to the law, a person cannot be pardoned if the person is yet to be sentenced by a court,” Hun Sen said on Facebook.

Not just Rainsy

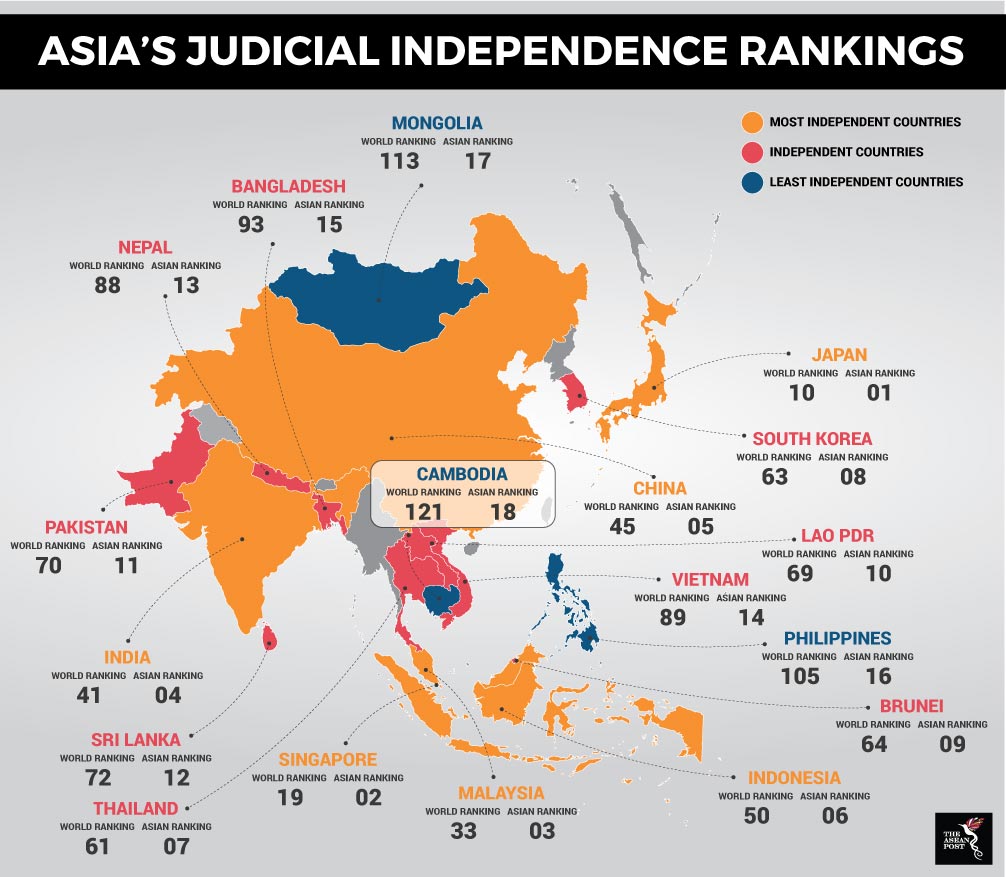

But Rainsy is not the only one who has expressed his lack of faith in Cambodia’s judiciary. In fact, a recent survey showed that the perception towards Cambodia’s judiciary system is the worst in the region.

Source: World Economic Forum 2018

The World Economic Forum (WEF) executive opinion survey conducted this year ranked Cambodia in 121st place among the 137 countries studied. In comparison, The Philippines was placed 105th, Vietnam 89th, Brunei 64th, Thailand 61st, Indonesia 50th, Malaysia 33rd, and Singapore 19th.

According to the WEF, the judiciary in Cambodia is the least independent from government influences and corruption in the judiciary there is said to be endemic. It also noted that rights groups have always criticised the government for undermining the independence of the country’s courts.

Sokha’s fate

Sokha’s lawyers have not taken kindly to the bet between Hun Sen and Rainsy. Soon after the bet, they issued a statement saying that any “release” of their client or having the charges against him dropped came under the authority of the court and should not be the subject of a “bet”.

They also warned that the “bet” between Hun Sen and Rainsy could “affect the procedure of the court”.

“The co-lawyers understand that using his Excellency Kem Sokha’s [situation for political gain] with [this] bet is making our nation suffer. We call on Cambodian politicians to remain moral as a good example for the next generations,” the statement said.

The problem with the bet is that it creates a situation where releasing Sokha will look bad either for Hun Sen – if he does indeed hold sway with the courts – or for the judiciary system itself. Sokha’s release would hint at a possible lack of judicial independence even if it was not true. In effect, the only decision that would look unbiased is if Sokha is not released.

Who’s trapping who?

Hun Sen is completely aware of the trap that Rainsy was attempting to spring on him. In response, Hun Sen has asserted that it was not him who was being trapped but Rainsy himself. This may be Hun Sen’s belief but, at least on the surface, it does indeed look like the Cambodian prime minister is caught between a rock and a hard place.

On the one hand, releasing Sokha would look like Rainsy’s suspicions were indeed correct. On the other hand, choosing the other route would mean to risk losing Cambodia’s largest trading partner: the European Union (EU).

Today, several countries have shown their interest to trade with Cambodia and as long as China is invested in Cambodia’s wellbeing then Hun Sen will have a strong, reliable ally. Even the Western world has a lot to gain from Cambodia’s development.

In the end, it is human rights watch groups who must tread carefully when dealing with Hun Sen if they truly believe the judiciary is under his influence. Because of the interest that other countries have shown, Hun Sen may decide that the best move would be to ensure Sokha is not released after all. Not only will it save him blushes and the judiciary’s integrity, it will also mean having Rainsy in his continued grasp. Driving Hun Sen into a corner may prove disastrous for Sokha and those who claim to champion human rights would have to share some of that blame.

Related articles: