Much has been written about the importance of financial inclusion for rural communities in Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam. The benefits are obvious even to armchair economists.

An Asian Development Bank (ADB) study focusing on Indonesia, the Philippines, Cambodia and Myanmar reports that if efforts were made to reach all unbanked peoples, gross domestic product (GDP) could increase anywhere between nine percent and 14 percent, even in bustling economies like those of the Philippines and Indonesia.

Successfully offering banking services and products to every single Cambodian is estimated to boost the country’s GDP as much as 32 percent. For those earning less than US$2 per day, that would translate to a 10 percent increase in income for Indonesians and Filipinos, and an increase of approximately 30 percent for Cambodians.

To offer some idea of the huge opportunities that exist; in 2016, only 31 percent of Vietnamese had access to a formal bank account, a whopping 95 percent of people in Myanmar were unbanked as of 2015, and only 24 percent had a savings account in Lao PDR as of 2014 and 17 percent of Cambodians in 2015.

How microfinancing helps

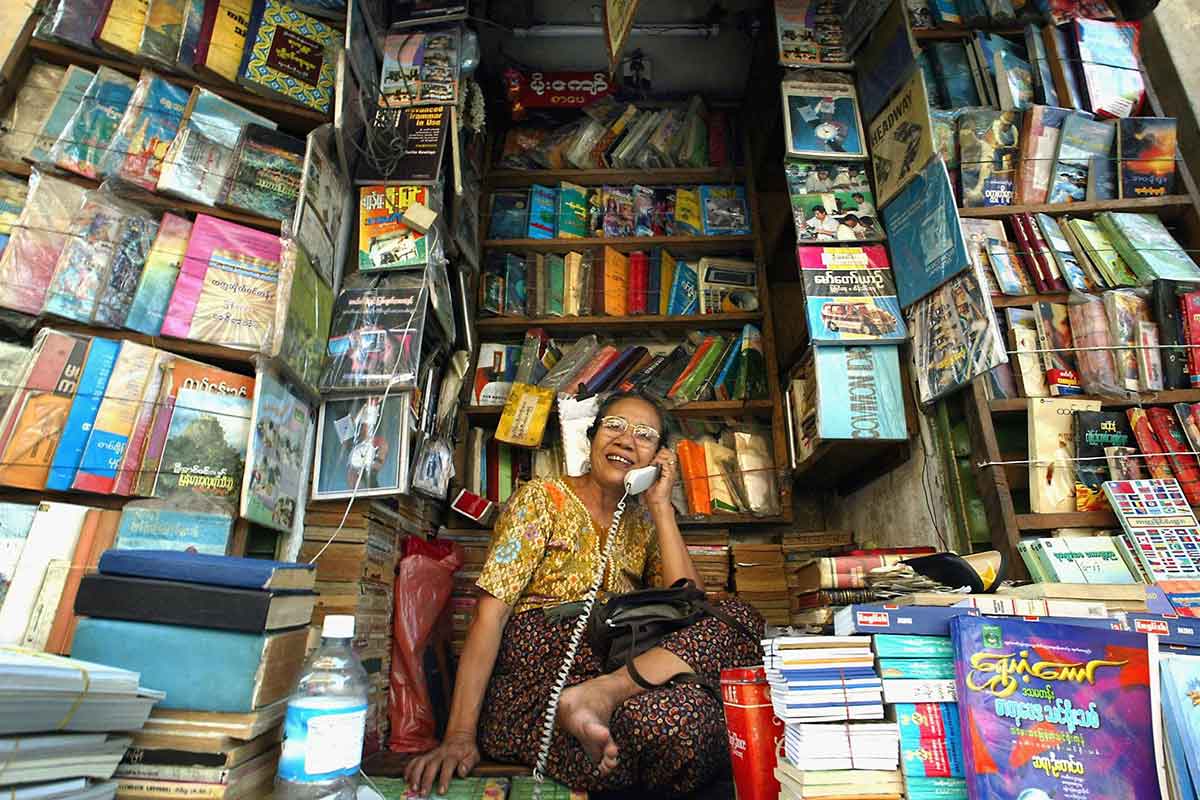

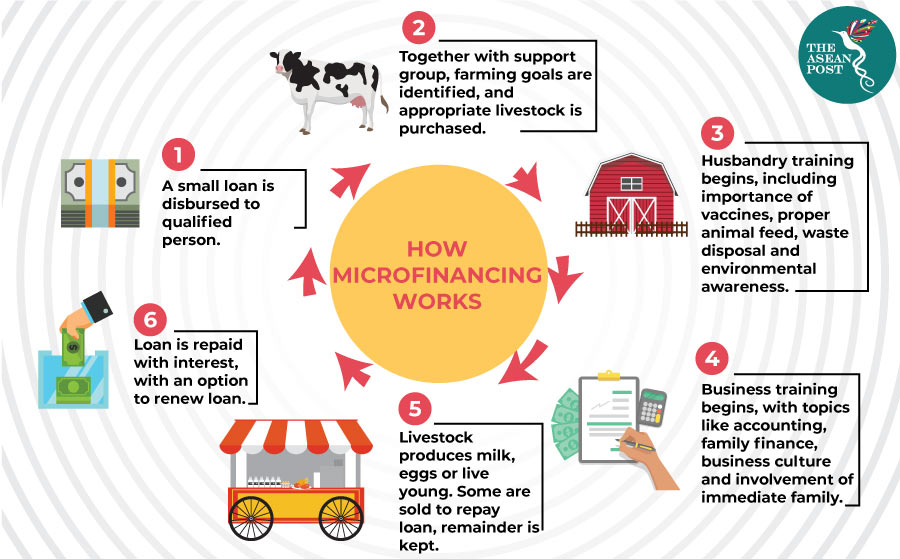

One particular area of interest under the financial services umbrella, is microfinancing. By distributing small loans and accepting small savings amounts, microfinancing empowers those below the poverty line to improve their livelihoods.

It motivates them to create sustainable sources of income and also provides self-employment for their children and other family members. If followed through under specific guidelines, the potential to reduce poverty is immense. Taking cues from the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh, the microfinance model there has shown the poor to be creditworthy, able to repay loans on time and with interest.

However, microfinance models can only work if applied to genuinely poor and disadvantaged beneficiaries, especially women. Observations repeatedly conclude that women almost always spend their money to help their families. And with weekly support meetings, women borrowers also have a better track-record when it comes to repayment as opposed to males.

In addition, complementary elements like microinsurance and remittances both, protect vulnerable families from health shocks and enable bread-winners to send cash quickly wherever it’s needed.

Challenges

Microfinancing is not without its challenges. Institutions like Malaysia’s Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM), the Bank of Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives (BAAC) in Thailand and Bank Indonesia (BI) have had to severely streamline practices to accurately define the poor. Leakage of funds to non-poor or near-poor households defeats the purpose of microfinancing because neither are below the poverty line.

Furthermore, sending out adequately motivated field staff is imperative to the success of microfinancing. These front-liners not only canvass for genuine applicants but build a culture of credit discipline and collective responsibility in each village they cover. These staff members are tasked with discussing new loan applications and loan utilisation. They must also be able to negotiate community issues.

Risk mitigation tools, access to markets and techniques to expand production come next. This way, households have everything they need to build assets over time. To ensure a long-lasting positive effect, the institutions that provide micro loans must themselves be financially viable.

Making a profit is important to build up equity, attract capital investment and instil a philosophy into program implementation staff that is consistent with what they themselves expect of their clients that are poor. Clients in turn need positive role models if they are to scale-up their own businesses.

Microfinance is not a silver bullet but it does provide a tangible and calculable boost to poor communities in their efforts to escape the cycle of poverty. Providing financial resources to as many deserving households across ASEAN as possible offers hope to policy makers wanting to raise the living standards of their citizens.

It is a tried and tested method for overcoming poverty as well as creating a self-sustaining workforce that will in turn help drive ASEAN to become the world's fourth largest economy by 2050. It all begins with governments and private entities insisting that institutions adopt financially sustainable practices.

In this way, they would help in ensuring that the poor are not left behind.

Related articles:

Big data is revolutionising microfinancing

The potential of big data for microfinancing in Southeast Asia