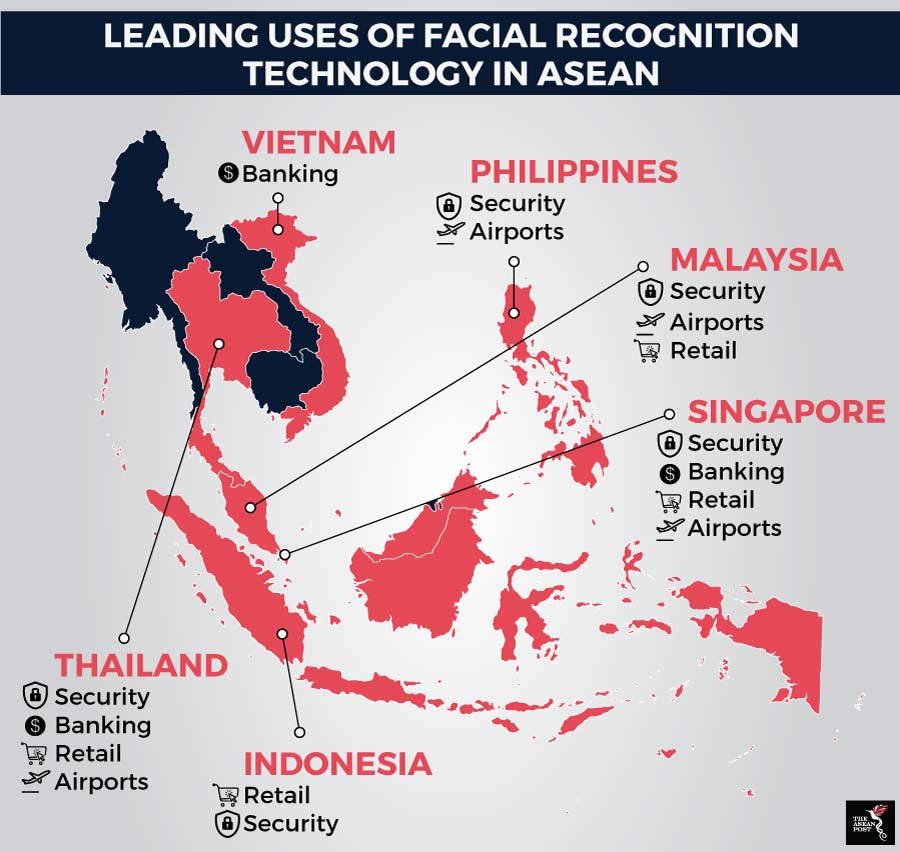

From boarding a plane to paying for groceries, facial recognition has become a part of our everyday lives. Once associated with Hollywood science fiction movies, facial recognition technology today is rapidly gaining use in Southeast Asia by law enforcement agencies, banks, airports, retail outlets and even residential communities.

Although this transformative technology has existed since the 1960s, it is only in the past decade that facial recognition has come to the fore-front after a slew of Artificial Intelligence (AI) deep learning techniques.

Because of increased airport security post 9/11 and other 21st century threats, facial recognition combined with other biometric and surveillance technologies has been seen as the solution to several security issues and has been adopted across the world.

Globally, research firm Technavio estimates the facial recognition market to be worth US$6.5 billion by 2021, up from US$2.3 billion in 2016.

Smart cities, fewer civil liberties

At the fore-front of technology in Southeast Asia, Singapore rolled out facial recognition technology in Changi Airport’s new Terminal 4 which opened in October 2017. Offering self-service options at check-in, bag drop, immigration and boarding, airport authorities say the technology makes for fewer queues.

Last October, Singapore firm ST Engineering won the tender for Singapore’s Lamppost-as-a-Platform (LAAP) project which will see a potential 110,000 existing lamp posts fitted with sensors and cameras that can collect a wide range of citizen surveillance data.

Local media reported that government agencies in Singapore could use the surveillance information to increase their situational awareness, detect potential problems and respond quickly to incidents such as unruly crowds, train breakdowns and traffic congestion.

As part of its Smart Nation project, the Singaporean government also plans to use other sensors on these lamp posts to collect and monitor data for air quality, water levels and foot traffic.

However, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong was adamant he did not want the implementation of the Smart Nation project to be “overbearing, intrusive and unethical”.

Earlier this year, Penang became the first state in Malaysia to launch a facial recognition system which is aimed at enhancing the capabilities of the existing 767 CCTV cameras already installed by the Penang City Council.

Penang’s police chief A. Thaiveegan said the move would improve the force’s efficiency while the state’s chief minister Chow Kon Yeow said he hoped the rest of the country would follow their example.

Last June, the Philippines’ Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana said the country’s military will soon acquire facial recognition software and drones to help in combatting terrorism.

“We are looking at facial recognition software so that we can easily track down the bad guys,” Lorenzana told the media.

In Thailand, the 7-Eleven chain of convenience stores announced plans to introduce facial-recognition and behaviour-analysis technologies in its 11,000 stores across the country. Reports last March stated that the technology – which is already seen in Thai banks – will be used to collect and analyse in-store traffic data as well as make product suggestions to customers.

Source: Various

Overbearing, intrusive and unethical

Prinya Hom-anek, a cybersecurity expert in Thailand, said the adoption of facial recognition and other AI technologies could raise privacy concerns.

“If a shop-owner installs a camera embedded with a deep-learning machine that could recognise the faces of everyone walking in or passing by his shop, then what is individual rights? Many may not be happy with it,” he said.

Although he supported the use of AI technology for financial transactions, Prinya stressed it should be done with tighter authentication requirements such as including an additional personal identification number (PIN).

Globally, concerns about privacy intrusions, the erosion of civil liberties and a lack of a proper legislative framework have been drowned out by governments, tech companies and large corporations who extol the virtues of convenience, speed and security.

Microsoft’s president Brad Smith has been vocal about the technology, raising ethical concerns about the growing trend just last month.

“The facial recognition genie, so to speak, is just emerging from the bottle,” Smith said. He also emphasised that tech companies should not have to “choose between social responsibility and market success.”

“We believe it’s important for governments in 2019 to start adopting laws to regulate this technology. Unless we act, we risk waking up five years from now to find that facial recognition services have spread in ways that exacerbate societal issues. By that time, these challenges will be much more difficult to bottle back up.”

The double-edged sword of facial recognition is perhaps nowhere more evident than in China – the world’s biggest market for security and surveillance technologies. China’s vast network of cameras and other tools under its national monitoring program, ominously known as Sky Net, helps police name and shame citizens for minor offences such as jaywalking.

While the technology also helps to arrest criminals – more than 2,000 as of last March – and to reunite missing people with their families, it is increasingly being used to monitor dissidents and minorities as well.

With already 170 million cameras as of 2017, Beijing plans to install another 400 million units across the country by 2020; boasting that it can scan the country’s entire 1.4 billion population in just one second.

As facial recognition technology becomes increasingly prevalent in Asia, better legislation and transparency with regards to data collection and storage will go a long way to creating proper checks and balances to ensure the technology is not abused.

Related articles:

Using facial recognition tech to combat terrorism

Smart Nation: Singapore's Intelligent Transport System (ITS)

Uyghurs abuse: Muslim governments silent