Governments have imposed drastic measures to contain the deadly COVID-19 outbreak. To date, over three million people have been infected, killing more than 200,000 worldwide. Although reports claim that some countries are gradually flattening the coronavirus curve, half of humanity are still currently under some form of lockdown or restricted movement. People are urged to self-isolate and practice social distancing.

For the first time in a very long time, humanity is experiencing “a feeling of exclusion from normal life and a sense of isolation”, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF). Nevertheless, for persons with disabilities, the sense of isolation and daily experience of exclusion is nothing new and is considered a norm for many. It is estimated that 15 percent of the world’s population has a disability.

As huge populations are anxious and impatiently waiting for businesses to resume and for life to return to normal after the pandemic subsides, the 1.3 billion people living with a disability will most likely continue doing so in their current environments.

“People with disabilities are among the world’s most marginalised and stigmatised even under normal circumstances,” said Jane Buchanan, deputy disability rights director at Human Rights Watch (HRW). The organisation has urged governments to make extra efforts to protect the rights of people with disabilities when responding to the pandemic.

Barriers to accessing public health information and implementing basic hygiene measures such as handwashing are some of the complications faced by the disabled, noted the World Health Organisation (WHO). Other than that, those institutionalised may find it difficult to enact social distancing because of additional support needs. Moreover, the new coronavirus may also exacerbate existing health conditions, particularly those related to respiratory and immune system function.

“Without swift action by governments to include people with disabilities in their response to COVID-19, they will remain at serious risk of infection and death as the pandemic spreads,” explained Buchanan.

Just last month, it was reported that the partners of General Election Network for Disability Access (AGENDA) from Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines held a call to discuss the barriers that citizens with disabilities encounter during the pandemic. Based on a report by the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), the main concern that the ASEAN member states identified was the access to information as many television stations in their countries do not include sign language interpretation.

The HRW and WHO have suggested that all governments should consider the specific needs of people with disabilities when developing prevention strategies. For instance, providing captioning and sign language for all live and recorded events and communications, including national addresses, press conferences and live social media events.

Other than that, the WHO also recommends that governments develop accessible written information products by using appropriate formats with structured headings, large print, braille versions and formats for people who are deafblind. Moreover, additional guidelines on hand washing should also be developed for those who are unable to wash their hands frequently on their own, noted the HRW.

Deaf-Blindness

Living with a disability is difficult enough, let alone for those who are unable to see and hear.

"Our way of communicating and our culture, everything relies on touch," said Ashley Benton, deaf-blind services coordinator for the state of North Carolina in the United States (US).

"Now we're not allowed to touch, and we have to practice social distancing," she told local media.

Other than new challenges to resume their daily lives amid the pandemic, another concern has been raised by the HRW regarding accessibility to quality and inclusive education. Schools were among the first institutions to be closed when the pandemic first hit ASEAN member states. Students have since started distance learning where classes, lectures and exams are carried out online. Although many students and educators have raised concerns about their struggles when conducting and learning via video conferencing applications, children with disabilities have their own sets of challenges as well.

“Children with different disabilities may be excluded if online instruction is not made accessible to them, including through adapted, accessible material and communication strategies,” noted the HRW in a statement. For example, the Youth Association of the Blind based in Lebanon reported that online classes and distribution of lessons are generally not accessible for students who are blind or have low vision.

Could Southeast Asia’s children with disabilities be experiencing the same consequences as visually-impaired students in Lebanon?

Mental Institutions

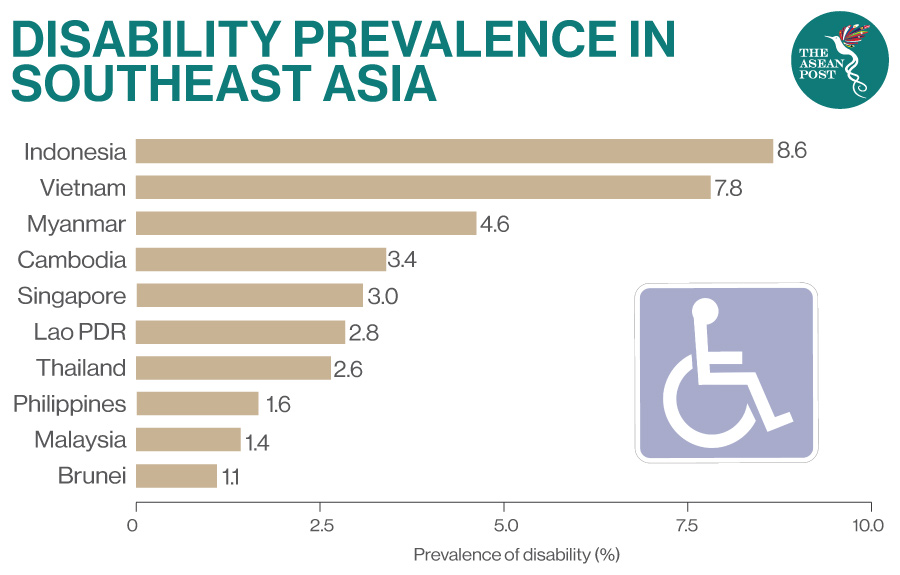

Based on media reports, Indonesia’s president Joko Widodo said that he planned to implement stricter rules and mobility on social distancing. The most populous ASEAN member state has reported over 9,000 COVID-19 cases with 765 deaths as of 27 April – the highest number of fatalities in the region.

“I’m (now) ordering large-scale social limits, physical distancing needs to be done more sternly, more disciplined, and effectively,” said Widodo in a cabinet meeting.

Nevertheless, physical distancing is not a luxury everyone can afford, especially those living in urban slums, refugee camps, prisons and institutions.

According to Yeni Rosa Damayanti, Chairperson of the Indonesian Mental Health Association, the current pandemic-related conditions in mental institutions in the archipelagic state are quite worrisome.

“In many institutions, there are about 20 to 30 people with disabilities living in one room,” she told the International Disability Alliance (IDA), an umbrella organisation focused on improving awareness and rights for individuals with disabilities. She also confirmed that psychiatric wards in the country lack disinfectants and basic sanitation supplies – a requirement when fighting the virus.

“Since mental institutions do not consider people with psychosocial disabilities as capable of thinking, almost all of them do not have access to information. There are no phones, no internet, no media, no television, they're cut off from the rest of the world and they're lacking in information about COVID- 19,” Yeni Rosa Damayanti explained.

She also warned that under current circumstances, mental institutions in Indonesia may turn into “a perfect petri dish for coronavirus outbreaks”.

The HRW has pushed for governments to protect those with disabilities during the pandemic and to consult with them regularly to ensure policies meet their needs. “Other catastrophes loom if millions of people are left out of the COVID-19 response,” said Jane Buchanan.

Related articles: