Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen recently revealed that he will be asking for a royal decree to grant permission for more than 100 senior members of the now-dissolved opposition party, Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) to re-enter politics based on “individual merit,” following a ban last year. The ban led to a controversial yet overwhelming win in the recent election on 29 July for Hun Sen and his ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP).

Following the electoral win, Cambodia’s one-party National Assembly is preparing an amended version of a draft law on political parties for a vote on 13 December. If accepted, it will allow 118 officials to re-enter politics. It does not, however, provide for the reestablishment of the CNRP.

Critics see the move as a step towards easing international pressure on Hun Sen’s government following the limiting of democratic freedoms which ultimately led to the CPP winning all 125 seats contested during the July election. That international pressure came in the form of Cambodia’s largest trading partner, the European Union (EU), which threatened to pull out of the Anything But Arms (ABA) trade deal with the Kingdom.

Last Wednesday, reports quoted Hun Sen as telling an audience during an event in Kampong Speu province that he will ask King Norodom Sihamoni to re-establish the political rights of only those 118 officials who had “shown respect for the Supreme Court’s ruling,” and vowed to imprison any who violated the ban. He said that “each official needs to make an individual request” to have their rights reinstated.

Ripping apart a torn opposition

Radio Free Asia quoted political analyst Kim Sok as saying that Hun Sen was attempting to split the CNRP, like he has with other parties in the past.

“Hun Sen is facing a dead end (because of international pressure), so the CNRP must maintain its firm stance and not fall for his strategy,” he said.

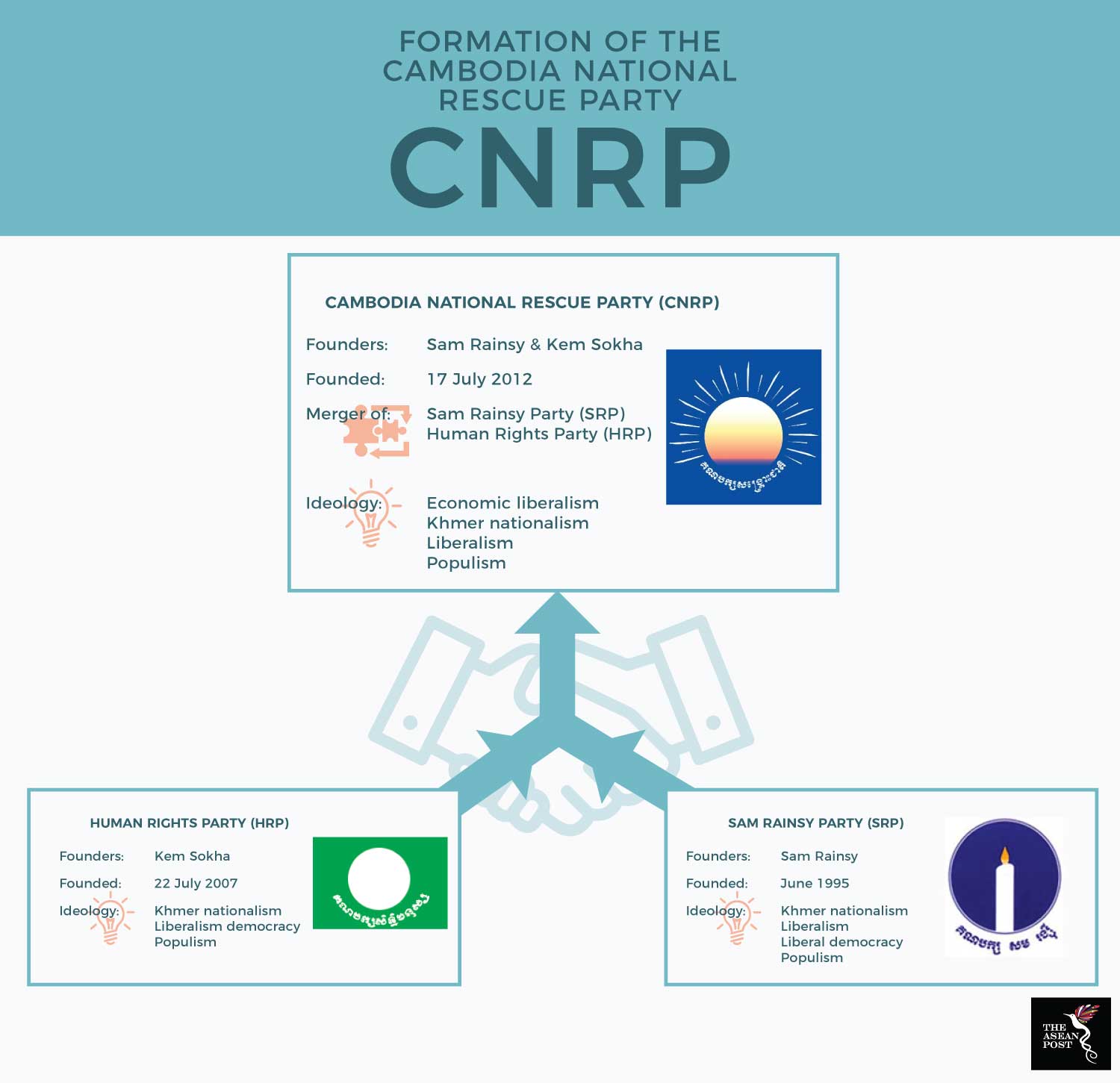

The CNRP was originally formed when two distinct opposition parties led by Sam Rainsy and Kem Sokha, respectively, merged. Following Sokha’s arrest, the party quickly splintered again along the same alliances. It appears as though there was no contingency plan and spats between supporters of Rainsy and Sokha were frequent, a recent example is the bet Rainsy made with Hun Sen on whether Sokha would be released.

Source: Various sources

Source: Various sources

Earlier this month, the CNRP alliance faced another tough test when Rainsy, its self-exiled former leader, said that he was seizing back the party leadership from Sokha, his successor, until the latter is released from house arrest. The decision was announced at a meeting that took place from 1 to 2 December in Atlanta, United States (US) which was attended by only the faction of the CNRP with roots in the Sam Rainsy Party (SRP). Those linked with Sokha’s Human Rights Party (HRP) refused to show up, choosing to boycott the meeting.

Sokha, immediately rejected the legitimacy of the Atlanta meeting through a statement attributed to his lawyers and posted on his Facebook page the same day. Under the terms of his release from prison, Sokha is not allowed to speak to the public, the media, or his former colleagues. The issued statement, however, had also asserted Sokha’s right to issue statements through his lawyers.

Calling Hun Sen’s “bluff”

Rainsy has called on all 118 officials to reject Hun Sen’s demand they request to have their political rights reinstated. Instead, Rainsy insisted that any deal must include the release of Sokha, who remains under house arrest.

Rainsy suggested that international pressure was working and that it would soon lead to Hun Sen freeing Sokha, reinstating the CNRP, dropping all charges against members of the opposition, and returning elected seats of government to the party’s officials.

“Hun Sen can’t avoid it, so he is trying to trick the CNRP by offering a partial solution that will likely require its officials to defect to the ruling party. No one should fall into his trap - don’t feel threatened and please remain calm. Hun Sen must provide us a full solution,” he said.

Whether or not Rainsy is correct in calling Hun Sen’s “bluff” remains to be seen, but as long as that is the case, it remains a real risk for the 118 officials involved. The fact that the alliance within the CNRP isn’t very strong suggests a possibility that at least some of the 118 officials may take up Hun Sen’s offer. However, if Hun Sen is indeed bluffing then remaining firm will be in the best interest of all the 118 officials. The final outcome will be a true test of the CNRP’s mettle and depends largely on whether the alliance is able to stay its suspicions of one another and truly band together as a strong party.

Related articles: