According to Malaysia's Health Ministry's (KKM) Guide to Nutrition Labelling and Claims, manufacturers must be aware of nutrient content claims and the conditions for their use.

For example, one of the conditions listed in the guide states that the food product must contain a range of nutrients including carbohydrates, fat, protein, vitamins and minerals for it to be labelled as "nutritious."

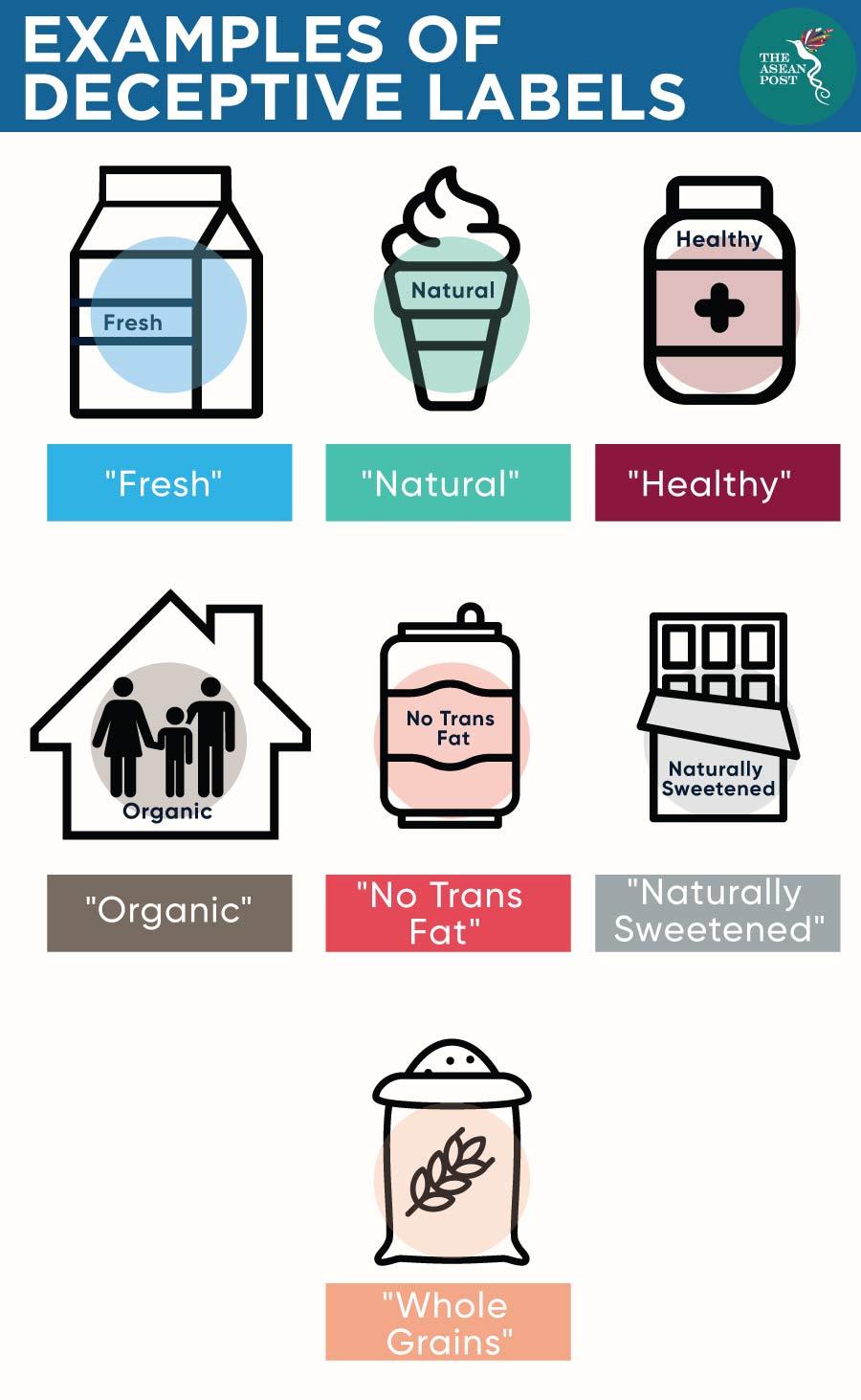

Marketing strategies are sometimes developed to bypass legal requirements – and the people responsible for them are getting more creative. For example, under the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines, any food can be labelled "no added sugar" as long as sugar (or any ingredient containing sugar) is not added during processing.

This means that any product including ice cream or even tomato sauce, can contain as many naturally occurring sugars as needed to keep the product sweet as long as more sugar is not added while it is being made.

The same marketing technique can be found in 'natural' labels, of which the FDA has not provided specific guides on the use of the term and therefore has resulted in the usage of the term for a wide range of products.

A survey by American non-profit organization, Consumer Reports in 2016 found that consumers associate the word 'natural' with organic, preservation free, and made without genetically modified ingredients. The reality is that even potato chips can be labelled as natural, due to using natural potatoes, but it does not exclude the high fat and sodium content.

These terms are already misleading for adults and children will definitely be confused as well. In some Nordic and European countries, there are strict guidelines on how to market products for children. Countries like Belgium and Denmark have made it illegal to market to children altogether –making any kind of deceptive language illegal.

Such laws and regulations do not have a significant movement in ASEAN countries. Food companies are free to run campaigns and advocate the 'health benefits' of their products without proper validation.

In 2018, a Malaysian entrepreneur Vishen Lakhiani, criticised Nestle for marketing its MILO brand product as healthy and beneficial to a child's growth. Lakhiani made the video following an article by the New York Times in 2017 that claimed that nutritionists in Malaysia who approve labels on products were taking money from food giants.

MILO is a chocolate drink that is very popular in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. Lakhiani’s video analysed the contents of MILO - including the fact that it contains 40 percent sugar.

While Nestle has defended the advertisement by stating that half the sugar comes naturally from milk and malt, which are sources of vitamins and minerals – a second video was later released exposing more ingredients in the company’s other products that do not reflect the health benefits advertised.

Diabetes is a major health concern in Malaysia, and the prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) has escalated to 20.8 percent in adults above the age of 30 – affecting 2.8 million people.

The Malaysian government imposed a "sugar tax" in 2019 to address the country's growing number of obese people. The sugar tax of RM0.40 (US$0.10) is imposed on every litre of sweetened beverage only.

However, the question remains whether Malaysians are aware of the significant amount of sugar in products advertised as beneficial for adults and children. For example, campaigns such as the "Back To School Mums" by Nestle MILO that encourages mothers to give MILO to their children so that they can have enough energy for the entire school day does not come with a warning that MILO has a high sugar level or the fact that the product could increase a child’s chances of becoming obese.

Elyza Ismail, who runs a business selling plus-sized clothes, said that before she attended an obesity awareness class, she did not know that MILO, the Nestlé breakfast drink, contained so much sugar.

“I had this idea of MILO as healthy and strong,” Ismail said, repeating an advertising slogan that has echoed in the ears of unsuspecting Malaysians for years.

Related articles: