There were many topics discussed during the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) annual meeting at Davos last week. Not surprisingly, climate change and the reduction of carbon emissions took centre stage, with the likes of Swedish climate change activist, Greta Thunberg calling for a zero-carbon footprint.

Speaking on a panel with Thunberg was Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, President of the Association for Indigenous Women and Peoples of Chad. What she had to say struck audiences – the deadly effects of climate change that is already happening in the Sahel region.

“When the indigenous say that the forest is burning, it is not just a language of expression – it is our real home that's burning. Indigenous people from all over the world – Chad, Amazon, or Indonesia –we depend on these forests, which is our food, our medicine, our pharmacy, our education,” said Ibrahim during a panel discussion at Davos.

Unusually heavy rains have damaged and washed away crafts, while drought has dried up food. Southeast Asia’s indigenous populations are no strangers to the environmental impact to their lives and livelihoods as described by Ibrahim – for whom climate action is taking too long. “When people talk about 2050, I'm like really, seriously? By 2050 there's no solution for this planet,” she exclaimed.

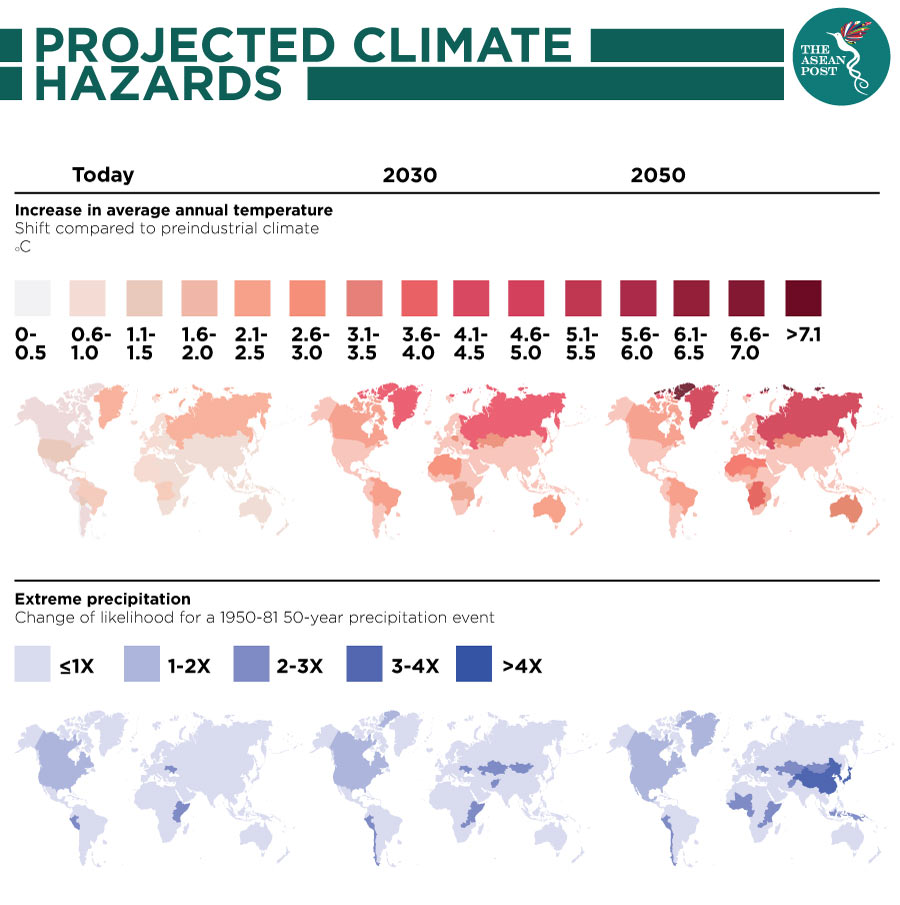

A recent report by McKinsey Global Insight (MGI) underlined that increasing temperatures expose rural populations in Asia and Africa to a dangerous physical threshold. It is hard to imagine what this means to people who rely solely on their natural environment. Not to mention, the role of governments and businesses responsible for clearing land, leaving indigenous groups to seek livelihoods elsewhere.

Climate change is very real for those who live on forest land. People have already died in Chad due to droughts, while scarce resources are forcing communities to fight among themselves. Ibrahim went on to explain the profound ways in which policymakers and businesses could benefit by including indigenous communities in the process when tackling environmental issues and restoring the deterioration of forests around the globe.

“We have the wisdom, we understand nature, we have developed the knowledge. We know how to adapt and we know how to restore forests that are burning,” said Ibrahim, also referring to the bushfires in Australia and the recent study that promoted aboriginal fire practices that will help manage bushfires and even regenerate healthier animals and plants within respective eco-systems. The report affirmed that while aboriginal knowledge on eco-systems is not valued in Australia, it does holds valid and important solutions.

“My grandmother is the best technology ever. She can predict the weather without a cell phone or internet.” added Ibrahim. By observing everything from migration habits to weather patterns, people like her grandmother have a close and respectful relationship with the natural world.

Indigenous communities have solutions

The term ‘fourth world citizen’ was first used to describe the condition of indigenous tribes in their respective countries – the relationships between ancient, tribal, and non-industrial communities and modern industrialised nation-states.

Today, the rights of the fourth world are still being forsaken – and what is more, valuable knowledge that could hold much needed solutions to the earth’s critical condition are being ignored.

Similarly, in Indonesia, wildlife conservation has been facing tremendous challenges. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) has been criticised for causing a decrease in the tiger population in Tesso Nilo National Park in Sumatra by removing the human element.

The entire area is now under foreign control with zero access for locals who previously had small farms in the area. With a long ancestral line tied to the area, these communities believe that the forests cannot survive without people. Thousands of small farms have been driven out of the area, resulting in a decline in wildlife populations.

Another report by the World Resources Institute (WRI) in 2016 identified that securing the land rights of indigenous people and other local communities in the Amazon region could prove to be a low-cost way to counter global deforestation and climate change.

What seems like an outrageous idea for politicians and businesses – to seek advice and guidance from indigenous tribes – could actually make the most sense. Indigenous communities have the most to lose to climate change. Their input of knowledge gathered through generations makes them experts that should be at the forefront of reforestation and regeneration.

“Businesses need us because we are the future, we are the solution as indigenous people. You need to listen to us, learn from us, and get your business sustainable. You cannot kill your partners, because for us nature is our partner, we protect it. And for you, you need to protect your business, so listen to us – we'll help you to do that,” concluded Ibrahim.

Related articles: