On 26 September, Indonesia was hit with yet another deadly earthquake, killing 37 people and damaging more than 6,000 houses. The country is one of the most disaster-prone in Southeast Asia and the world. Two weeks after the earthquake, however, news reports began emerging that Indonesians were still holed up in shelters. The reason? Panic brought on by fake news.

According to numerous news reports, fears about aftershocks had been aggravated by a stream of hoaxes and fake news which were mostly spread through WhatsApp and other messaging services which seemingly warned the receivers of those messages that a tsunami-generating quake was about to strike.

“It’s up to you if you want to believe me or not, but I talked with my relative and apparently Ambon is going to sink in the next few days,” one of the messages circulated on WhatsApp read. Ambon is the capital and most populous city in the Indonesian province of Maluku.

The panic came about despite the fact that, just a little over a month prior, efforts were made by the Indonesian Anti-Slander Society (Mafindo), Google News Initiative and the country’s Communications and Information Ministry to train members of the public to be able to spot disinformation or hoaxes on the internet.

Particularly targeting youths and housewives, a comprehensive media literacy programme called the Stop Hoax Indonesia programme, aimed to increase the public’s ability to verify information shared on social media through workshops was held in 17 cities.

The workshops were conducted at schools and campuses from August to November. The programme was launched alongside a Fact-checking Contest initiated by Mafindo to encourage the younger generation to fight hoaxes and to inspire fact-checking.

An internet nation

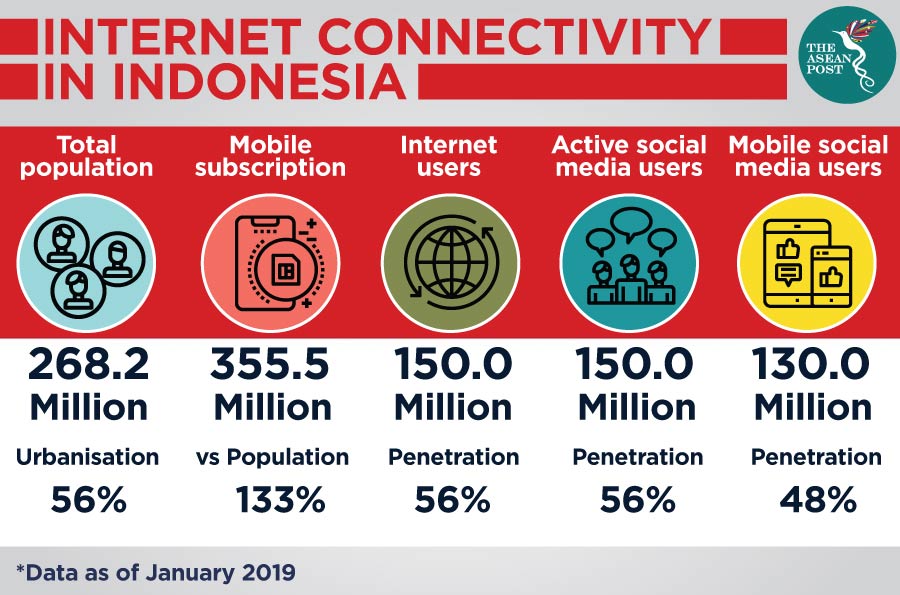

Indonesia – partly because of its size – is a significant player in the adoption of internet technology. At the start of the year, according to We Are Social, the Southeast Asian nation had 150 million internet users. This was an increase of 17 million (13 percent) compared to January 2018, but on top of this – and despite the whopping numbers – there is still room to grow as the 150 million only represents a penetration of about 56 percent.

But penetration (in terms of sheer size) is not the only area that Indonesia boasts of tremendous performance. The country is also seriously adopting better internet technology. One of the ways it is doing this is through the adoption of 5G.

This, nevertheless, comes with its own set of challenges. The spread of fake news being one of them.

Last weekend, the country’s Director General of Public Information and Communication at the Communications and Information Ministry, Widodo Muktiyo, claimed that “rapidly developing” progress of internet technology needed to be accompanied by adequate literacy among the public. Failing which, he said, would leave Indonesians facing a “culture shock”.

This “culture shock” could lead to numerous negative impacts, including widespread fake news. Widodo said that many were inclined to post or forward fake news as they did not know how to filter content well.

"They just post and share," he was quoted by local media as saying at the 2019 Public Dissemination Dialogue Forum, at Tersidi Lor Village Hall, in Purworejo district, on 16 November.

Widodo urged the public to exercise more caution when using the internet as, at times, fake news involved sensitive issues such as ethnicity, race, religion, inter-group relations, and politics among others. He said the spread of false news involving these issues could cause disunity.

"If (the internet) is used recklessly, it can trap its users. There are legal consequences that could lead to someone getting sent to prison.”

Widodo, who is also a professor at the University of Sebelas Maret (UNS) Solo, provided simple tips to help internet users avoid falling for fake news. First, if they come across news with questionable or doubtful content, they should cross-check the message with news from platforms with credible sources.

Secondly, they are advised to leave WhatsApp groups with content that is doubtful and may contain blasphemous messages.

"The internet and social media should make our lives easier, not potentially trouble us," he added.

The lesson is clear not just for Indonesia but the rest of ASEAN as well. As we continue to embrace technology, a general sense of caution, awareness and literacy must be inculcated in society.

Related articles: