Blessed with six million square kilometres of ocean territory, Indonesia’s fisheries industry could make a larger contribution to its economy if better managed.

Southeast Asia’s largest economy is the world’s second largest fish producer after China. The fisheries sector contributed over US$26.9 billion – or around 2.6 percent – to Indonesia’s gross domestic product (GDP) last year; a larger contribution compared to the fisheries sectors of its regional peers such as China, the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand.

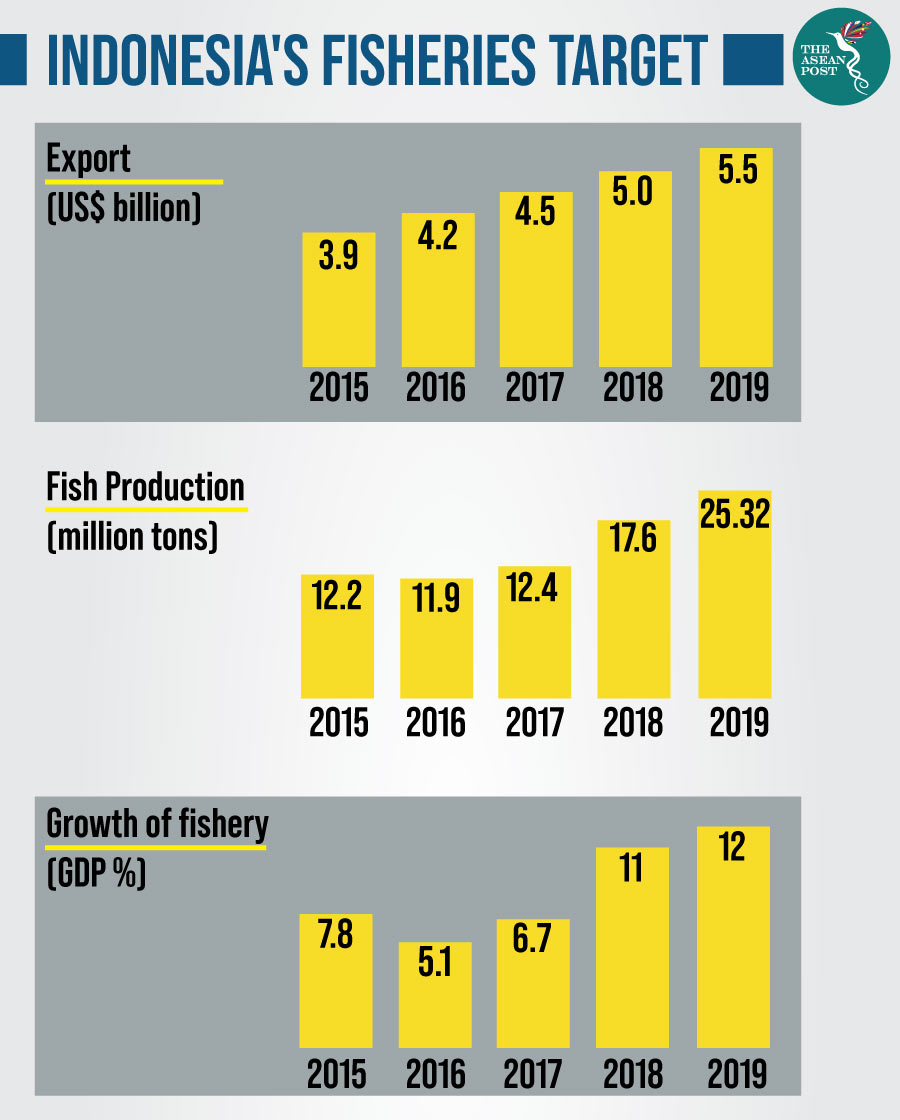

However, for a variety of reasons, Indonesia’s fisheries sector has been unable to meet both, its production and export targets since 2015.

While fisheries contributed to export earnings worth around US$4.1 billion in 2017, the World Bank notes that improvements to Indonesia’s fisheries management would add value of up to US$3.3 billion per year within 10 years.

Combined with an article from the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO) which states that the country loses more than US$7 billion worth of seafood a year due to wastage, and it is obvious Indonesia can do a lot more to harness the full potential of its marine resources – especially as 19 million Indonesians, or around eight percent of its population, are classified as undernourished.

Depleted stock

Historical and ongoing overfishing has depleted Indonesia’s fish stock, and data from the National Commission on Stock Assessments in 2017 showed that nearly half of the nation’s wild fish stocks were overfished – meaning their stocks have been partially depleted and their current and future productivity has been undermined.

While illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing has played a role in this, legal fishing and the expansion of the domestic fishing fleet has also impacted fish stocks in almost all parts of the country.

Slack pollution control measures have seen millions of tons of plastic waste and other hazardous material make its way into Indonesia’s oceans over the years, damaging delicate marine eco-systems which are already hurting from the effects of climate change.

Combined with data deficiencies and a lack of coordination among agencies, and it is soon apparent why Indonesia ranks 22nd out of the largest 28 marine fishing nations for fishery management effectiveness according to a 2016 study titled ‘Global fishery prospects under contrasting management regimes’ published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal.

Improve cooperation, better data, fishery-specific plan

The World Bank’s latest edition of its Indonesia Economic Quarterly released in July recommends three areas of reform to prevent overfishing and to ensure the industry’s sustainability. The first is the creation of a framework for decision-making that brings together governments, industry players and other stakeholders more effectively. Apart from clarifying roles and responsibilities, such a framework should also work towards better coordination.

Secondly, improving fishery data for evidence-based management is just as crucial. A report developed with the aid of the Packard Foundation in July 2018 titled ‘Trends in Indonesian Marine Resources and Fisheries Management’ highlighted how the quality of official fisheries statistics is variable, both at the global level and at the country level in Indonesia.

The report noted how one study found that tuna catch from small and medium-scale fishing vessels from the second-largest tuna port in Indonesia, near North Sulawesi, could be almost 40 percent higher than reported.

“It is important to recognise that catch data on over 1,000 different species of fish and invertebrates caught by well over one million fishers on over half a million boats, using multiple fishing gears and fishing grounds across the world’s largest archipelago is understandably an immense and difficult task,” noted the report.

Thirdly, implementing fishery-specific management plans – such as quotas and area closures – with stronger monitoring, control and surveillance will also be key. Importantly, small vessels that catch around 50 percent of the total harvest must be brought under evidence-based harvest controls over time.

These practices should complement efforts to increase fisheries’ fiscal contribution, which has traditionally always been low. Between 2011 and 2016, the fisheries sector’s ratio of tax-to-GDP contribution (0.26 percent) was well below the national cross-sector average of 11 percent.

Waste and loss

Indonesia is considered the world’s eighth most fish dependent country, with fish contributing 52 percent of all animal-based protein in the Indonesian diet – well above the global average of 16 percent.

However, a large amount of seafood never reaches dinner plates because of poor management.

Highly perishable, fish face a race against time to be transported from sea to local markets or foreign retailers – and their quality can rapidly deteriorate without proper management to transport and store them. On fishing boats, some fish that have been caught are discarded to save space in refrigerators and ice boxes for higher-value seafood. On land, fish can quickly rot if they are unloaded on jetties with no roofs or soaked in water for too long.

An article by officials from the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAP) and UNIDO in May found that poor fishery management leads to almost 40 percent of Indonesian seafood catch – or US$7.28 billion a year – being classified as waste or loss.

Bad distribution networks contribute 15 percent to this figure, with another nine percent lost due to poor processing and packaging processes. Bad fishing practices, such as throwing away unwanted catch at sea, potentially contribute to 8.2 percent – with another six percent of losses stemming from poor transportation and poor storage systems.

With Indonesia’s fisheries sector playing a critical role in providing food security and employment, the industry’s stakeholders should consider the risks that continued mismanagement poses to the long-term productivity and economic value of its fishery assets.

Related articles: