Labour Day - which falls on 1 May every year - was an eventful day in Malaysia. The ASEAN member state which recently reported a plunge in COVID-19 cases – announced plans to ease the country’s partial lockdown, known locally as the Movement Control Order (MCO). Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin said in a special address to the nation that the government will enforce a conditional MCO beginning 4 May. The announcement came earlier than expected for Malaysians as some believe the move to relax the MCO is “too soon”, as new COVID-19 cases increased over the weekend.

“Beginning May 4, almost all economic sectors will be allowed to open with conditions,” said the prime minister.

“This is important as business and work is a source of income. If we are under MCO for too long, we will not get any income and this will have a negative impact on our finances.”

The premier told local media that the lockdown had seen the country incur RM63 billion (US$14.6 billion) in losses, and if the MCO were to be continued for another month – losses would touch nearly RM100 billion (US$23.1 billion).

Malaysians took to social media to express their mixed emotions. A petition to cancel the conditional MCO was even posted online which had gained almost 500,000 signatures in just three days. Observers believe that it is still unsafe to go out in public, fearing that another wave of infections will hit the country.

Migrant Arrests

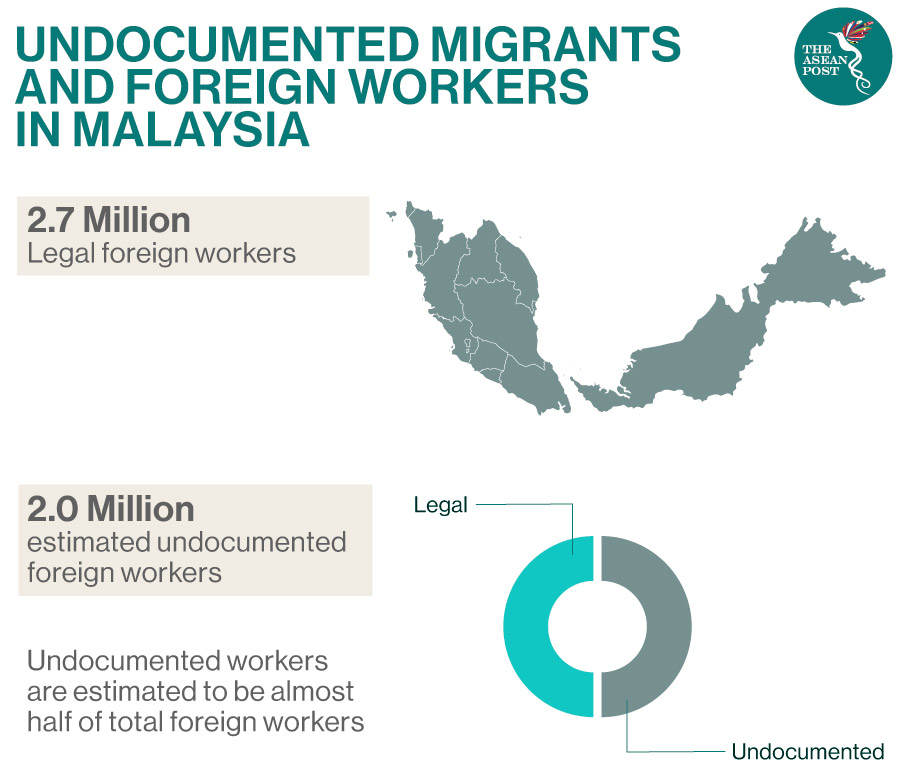

Later that day, it was reported that hundreds of foreigners and refugees were arrested in a migrant crackdown on COVID-19 red zones in the country. Heidy Quah, founder of Refuge For The Refugees (RFTR) – a non-governmental organisation (NGO) advocating for refugee children, said kids as young as four had been picked up in immigration raids.

“A 15-year-old refugee from Myanmar was texting me all the way from pick up to when they were dumped into the truck. His four-year-old brother was with him. Once they reached the immigration depot their phones were confiscated,” explained Heidy Quah to the media.

Authorities confirmed that 586 undocumented migrants were arrested. According to media reports, the detained include ethnic Rohingya refugees from Myanmar.

Recently, Malaysia has seen a rise in xenophobic sentiments against Rohingya refugees, accusing them of being a burden on state resources. A few anti-Rohingya petitions were posted online, demanding that they be deported from Malaysia. One petition even gathered over 20,000 signatures before it was taken down as it was considered hate speech. Organisations such as the Human Rights Watch (HRW) have criticised the country for turning its back on Rohingya asylum seekers amid the pandemic, following a report in April which stated that Malaysia had denied entry to a boat carrying around 200 Rohingya refugees.

"We, the Rohingya refugees in Malaysia, are worried and in a state of fear due to the growing negative sentiments against us as a result of such statements,” said Rohingya groups.

It was reported that forces from the civil defence, police and immigration conducted the operation and raided three low-cost apartment blocks in Kuala Lumpur, where many foreigners live. Police told the media that the move was aimed at preventing undocumented migrants from traveling to other areas amid the MCO, according to a local news agency.

As Malaysia is not a signatory to the 1957 Refugee Convention nor its subsequent 1967 Protocol – refugees are branded as illegal or undocumented migrants.

Rights group and activists have criticised Malaysia for the crackdown. The United Nations (UN) released a statement and voiced its concern over the matter, warning that overcrowded detention centres carried a high risk of increasing the virus’s spread.

“The fear of arrest and detention may push these vulnerable population groups further into hiding and prevent them from seeking treatment, with negative consequences for their own health and creating further risks to the spreading of COVID-19 to others,” read the UN statement.

It was reported that the government recently assured undocumented migrants that should they show symptoms of the virus, they should not be afraid in seeking help and identifying themselves to the authorities.

However, local activists believe that the recent move by the authorities might further discourage the vulnerable group from going out for testing and seeking treatment should they be infected.

Government’s Response

Malaysia’s Senior Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob responded to criticism specifically from Amnesty International by stating that the government has a duty to protect the country from “illegals”.

“What we did (arresting the illegals) was according to our country’s laws. Amnesty International, too, needs to respect our laws. As a sovereign nation, we have powers to protect our country and people,” said the minister during a press conference.

Ismail Sabri Yaakob told the media that all those who were detained had been screened and found to have tested negative for COVID-19. However, the migrants would be sent to immigration detention centres to await further action, justifying that “their presence here is still illegal” and “action must be taken against them under the law”.

Malaysia has seen mixed reactions from the general public. Some have applauded the operation against the undocumented migrants, while some have criticised the move, calling it “inhumane”.

Malaysians took to social media to protest against the “dehumanisation of migrants and refugees”. A poster of the online demonstration went viral, along with the hashtag #MigranJugaManusia (Migrants Are Humans Too) on Twitter.

World Press Freedom Day

On World Press Freedom Day yesterday, a prominent Malaysia-based journalist was called in for questioning by the authorities over her reporting of the migrant crackdown in Kuala Lumpur.

“According to PDRM (Royal Malaysia Police), I am being investigated under Sek 504 of the Penal Code and Sek 233 of the Communications & Multimedia Act,” said Tashny Sukumaran in a series of tweets.

Bukit Aman Criminal Investigation Department (CID) director Huzir Mohamed confirmed the probe against the journalist.

Local activists, journalists and rights groups were appalled by the actions of Malaysia’s police, which ironically happened on World Press Freedom Day. HAKAM Youth, a committee under the National Human Rights Society (HAKAM), issued a statement regarding the matter and expressed solidarity with Tashny Sukumaran.

“A move to silence those who disagree, the probe into the article is a threat to the press freedom of this nation as encapsulated under Article 10 of the Federal Constitution. It also impedes the step forward the enhancement of the freedom of expression and freedom of press, which has seen the nation being ranked 22 places forwards last year in the latest World Press Freedom Index,” noted the HAKAM Youth statement.

Related articles: