ASEAN’s reputation as a hub for fake medicine is nothing to sneeze at.

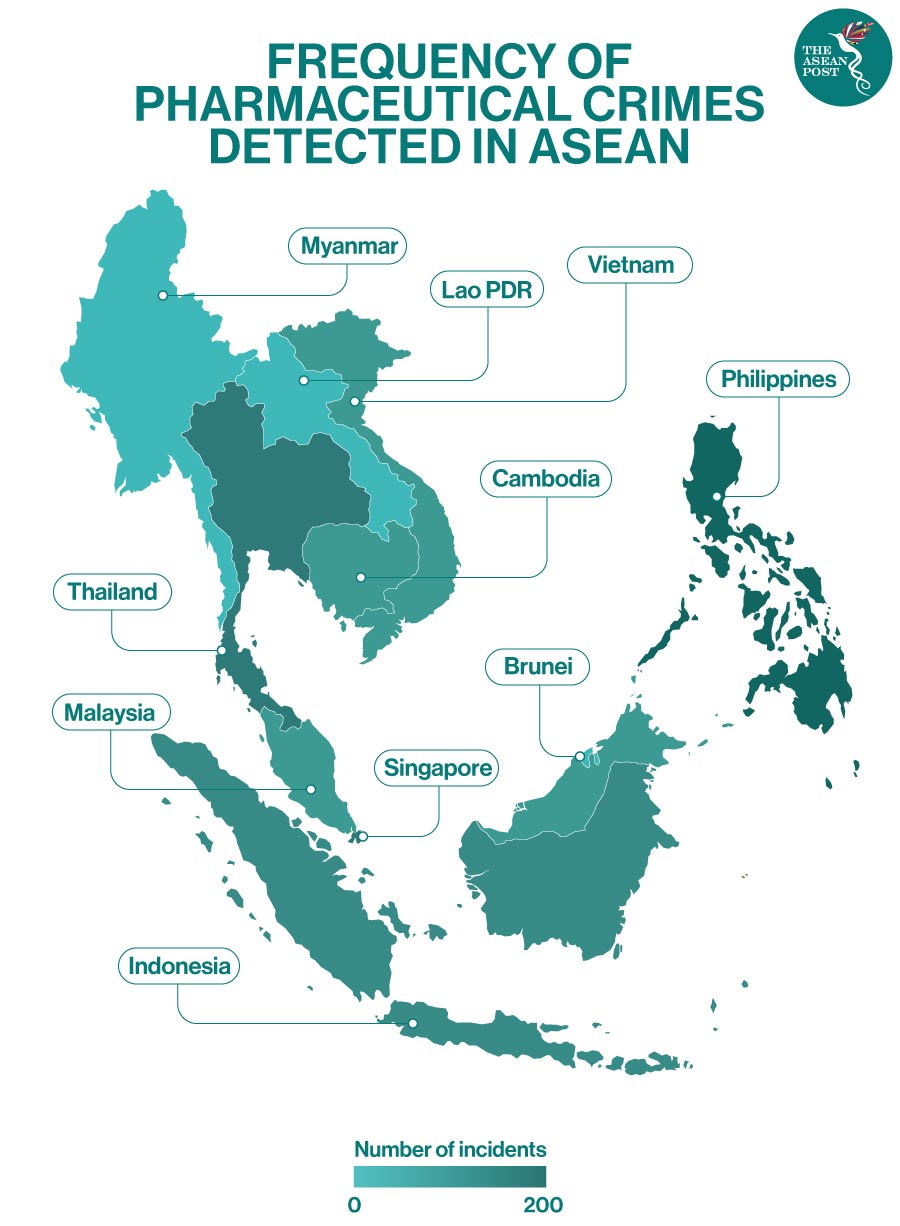

Increasing amounts of falsified medicines are being produced in the region, in part as a result of legitimate, and illegitimate, pharmaceutical producers based in India and China having transferred or outsourced some manufacturing processes to Malaysia, Vietnam, Myanmar and Cambodia to avoid tougher regulations and enforcement – and to benefit from lower production costs – according to a 2019 report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines counterfeit medicine as “one which is deliberately and fraudulently mislabelled with respect to identity and/or source.”

These counterfeit medicines range from falsified anti-cancer treatments to drugs for infertility and weight loss, and the issue is a greater threat in remote areas, where poor health systems may drive patients to rely on unregulated medicines providers.

Counterfeiting can apply to both branded and generic products, and counterfeit products may include products with the correct ingredients, wrong ingredients, without active ingredients, with incorrect quantities of active ingredients or with fake packaging.

“Best case scenario they [fake medicines] probably won't treat the disease for which they were intended,” said Pernette Bourdillion Esteve from the WHO. “But worst-case scenario they'll actively cause harm, because they might be contaminated with something toxic.”

Organised Crime

In ASEAN, the counterfeit goods and falsified medicines trade is among the region’s four biggest transnational organised crimes along with the illicit drug market, human trafficking and migrant smuggling and environmental crimes such as wildlife and timber trafficking.

The UNODC report titled, ‘Transnational Organized Crime in Southeast Asia: Evolution, Growth and Impact’ estimates the amount spent by consumers in Southeast Asia on falsified medicines to be between US$520 million and US$2.6 billion per year.

In 2010, the UNODC estimated the market was worth around US$4 billion.

In March 2020, crime control organisation Interpol coordinated a global operation targeting the online sale of illicit medicines and medical devices and seized more than 34,000 fake medical goods. Based on their report, the most counterfeited products are medicines (antivirals, herbal medicines and anti-malarial), medical equipment (face masks, disinfectants, fake coronavirus test kits, gloves and ventilators), and sanitisers (substandard hand sanitisers, soaps and cleaning wipes).

Likewise, the UNODC has also stated that previous tests have shown that 47 percent of anti-malarial medicines tested in Southeast Asia were found to be fraudulent – but the true figure could be much higher.

As the Malaysian Pharmaceutical Society notes, because counterfeiting is difficult to detect, investigate and quantify, it is hard to know or even estimate the true extent of the problem.

The WHO claims there has been “under-investment in supply chain systems and regulatory systems” for pharmaceuticals in ASEAN, so it should come as no surprise that corruption plays a significant role in the trade of falsified medicines.

Legal Loopholes

Some trafficking networks have even recruited current or former pharmaceutical company executives and state officials with knowledge of national regulatory and industrial systems, and the arrests of a number of healthcare professionals in relation to falsified medicines highlights the severity of the issue.

In a case that shocked Vietnam back in 2017, six former executives of a private pharmaceutical company in Ho Chi Minh City received prison sentences ranging from two to 12 years after they were found guilty of forging paperwork to distribute fake cancer drugs – claiming it was manufactured by a company in Canada which investigators later found to be non-existent.

In an even more recent case, a former CEO of a Vietnamese private pharmaceutical company was sentenced to 17 years in prison late last year for smuggling fake cancer medicines.

“We are facing unscrupulous dealers, who are very familiar with the legal loopholes and know that nothing is currently being done to trace them,” said Bernard Leroy, Director of the Institute of Research Against Counterfeit Medicines (IRACM).

“In the absence of effective international cooperation like the ones working to sanction drug trafficking, magistrates have no means of dismantling the networks, or of locating and freezing the criminals’ financial assets,” he added.

Related Articles: