Last month, the Joint Action Group for Gender Equality (JAG) called for the Malaysian government to commit to a clear timeline to table the Sexual Harassment Bill after it was delayed. The bill covers protection mechanisms and processes, counselling, organisational responsibilities and the establishment of a tribunal.

A sexual harassment law would provide a clear definition of prohibitive conduct and outline the seriousness of the violation. A law could also mandate that all companies have in place proper mechanisms to protect employees and deal with harassment.

Culture of fear

As 2020 fast approaches, Malaysian women still face challenges of gender inequality which is symptomatic of the patriarchal system. The 2018 #MeToo global movement has given courage to women and men to speak out and expose the systemic nature of sexism and male entitlement. Women are no longer willing to be silenced when they are harassed and abused.

But such a powerful message was lost on the Malaysian government. Just last week, a senator from the People’s Justice Party (Parti Keadilan Rakyat) which is part of the ruling Alliance of Hope government proposed the enactment of a sexual harassment law to protect men from being seduced into committing crimes such as rape. His vacuous statement read, “I propose a Sexual Harassment Act to protect men from the actions, words and clothing of women, which can cause men to be seduced to the point they can commit acts such as incest, rape, molestation, (watching) pornography and likewise.” The Senator in question, Mohd Imran Abd Hamid said the law was important to protect men.

Wanting to protect men from sexual harassment is one thing, but creating a law that protects perpetrators is just vile. The All Women’s Action Society (AWAM) condemned Imran’s remarks saying, “it is the perpetrator who must take responsibility for their own actions. The idea that victims are unable to access justice or demand some form of redress after undergoing such a dehumanising experience simply adds to the creation of a culture of fear and violence.”

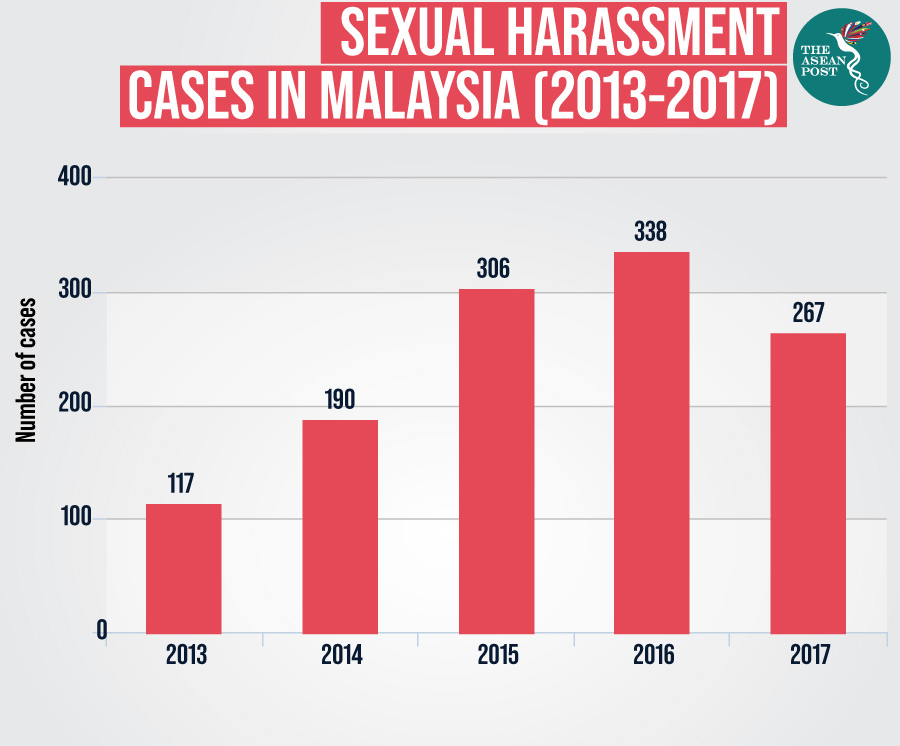

Sexual harassment can occur anywhere – from workplaces to campuses or in public places to places of worship. And it is not just exclusive to women, as any person of any gender can be the perpetrator or the victim of sexual harassment. Based on statistics from the Royal Malaysian Police (PDRM), between 2013 and 2017, out of a total of 1,218 reported sexual harassment cases, 79 percent involved victims who were women while 21 percent involved male victims.

Power and objectification

Gender-based violence including sexual harassment is typically assumed to be driven by desire or lust, but AWAM states that it is all about power and objectification. Sexual harassment is used to intimidate, disempower and discourage women in a male-dominated society. Many victims do not report their ordeal out of fear, while some are unsure of what conduct constitutes harassment and what doesn't.

The United Nations (UN), citing the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), describes sexual harassment as an unwelcome sexual advance, requests for sexual favours and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature either made explicitly or implicitly.

The latest survey conducted on 1,002 Malaysians by YouGov Omnibus found that 36 percent of women and 17 percent of men have experienced sexual harassment. From these percentages, only half of the victims reported or told someone of the incident, and women are more likely to report an incident than men, at 57 percent.

Hannah Yeoh, Deputy Minister of Women, Family, and Community Development said the flaws in mechanisms that are involved in reporting these cases are the reason that many incidents of sexual harassment still go unreported.

Women keep silent because, in many instances, they are questioned and doubted, and at times even re-victimised. To make it worse, the burden of proof is always placed on the victim. “In some instances, they shied away from reporting as they feared that no one would believe them. This was one of the obstacles that prevented them from lodging a report,” explained Hannah.

The YouGov Omnibus survey also found that the main reason people chose not to report sexual harassment is due to embarrassment or shame (54 percent). 38 percent chose not to report because they felt that no one would do anything about it, while 26 percent feared repercussion.

Malaysia’s Deputy Prime Minister Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail said there was still a certain stigma attached to victims reporting such cases. Often the workplace culture and policies are complicit in silencing and not supporting victims. And unfortunately, shame and silence has allowed sexual harassment in Malaysia to thrive.

This article was first published on 9 August, 2019.

Related articles: