Last week, Hollywood mogul, Harvey Weinstein was found guilty of sexual assault – including rape. At least 80 women had accused him of sexual misconduct stretching back decades including Hollywood stars like Gwyneth Paltrow and Selma Hayek.

Reports following the verdict say Weinstein suffered chest pains and was taken to the hospital directly after. He will soon be transported to the New York City jail complex on Rikers Island to await sentencing on 11 March.

The case against Weinstein prompted the #MeToo movement which encouraged victims to come forward and report sexual misconduct/harassment by powerful men.

The movement, started in October 2017, garnered international momentum. In its coverage, there has been widespread discussion about the best ways to stop sexual harassment and abuse – for those who are currently being victimised at work, as well as those who are seeking justice for past abuse and trying to find ways to end what they see as a culture of abuse.

There is general agreement that a lack of effective reporting options is a major factor that drives unchecked sexual misconduct in the workplace.

False reports of sexual assault are very rare, but when they do happen, they are put in the spotlight for the public to see. This can give the false impression that the majority of reported sexual assaults are false. However, according to a study published in the journal of Violence Against Women, false reports of sexual assault only make up two to 10 percent of the total number of reports – yet, it is one of the main reasons why women refuse to break their silence.

The #MeToo movement quickly moved from the entertainment industry to the government sector in the United States (US). At least 138 government officials have been publicly reported for sexual harassment/assault since the 2016 US general election. A study by the Georgetown University in 2018 later found that one in every four government officials accused of sexual misconduct in the #MeToo era is still in office today.

The study also found that sexual assault is already one of the most underreported violent crimes in the United States (US), with 70 percent of victim never reporting to the police. Imagine then, the extent of the underreporting that could be going on in Southeast Asian countries where the subject is taboo and victim blaming is prevalent.

Although Asian countries like Japan, South Korea and India have seen increasing numbers of women speaking out against sexual misconduct, Southeast Asian countries have largely remained silent. Some headway had been observed in the Philippines in 2018, where women flooded social media and the streets in protest against President Rodrigo Duterte’s sexist comments, under the hashtag #BabaeAko (I Am Woman).

In Indonesia, reporting sexual harassment can land a woman in jail. Baiq Nuril Maknun, a 41-year-old school administrator from the city of Lombok who recorded her school principal's sexually suggestive phone calls was slapped with a six-month jail sentence plus a 500 million rupiah (US$35,880) fine.

“Our law enforcers lack sensitivity and understanding when it comes to sexual harassment and violence cases,” said Dhyta Caturani, founder of Jakarta-based women’s rights activists collective PurpleCode. “Nuril’s case shows they aren’t siding with the victims and punish them instead. This is how Indonesia’s law enforcement view the victims of sexual harassment and violence, so I won’t be surprised to see if there will be other Nurils in the future.”

Following public outrage on the matter, President Joko Widodo granted amnesty to Baiq Nuril Maknun after the Supreme Court rejected her appeal. The mother of three wept as she told Indonesia’s Parliament, "don't let anyone else have an experience like mine."

In 2019, a survey by YouGov Omnibus found that 36 percent of women and 17 percent of men in Malaysia were victims of sexual misconduct, while only 53 percent of female victims and 44 percent of male victims actually reporting about it.

The study also found that the main reason people chose not to report sexual harassment was embarrassment and feeling that no one would do anything about the problem and fear of repercussions – such as victim blaming.

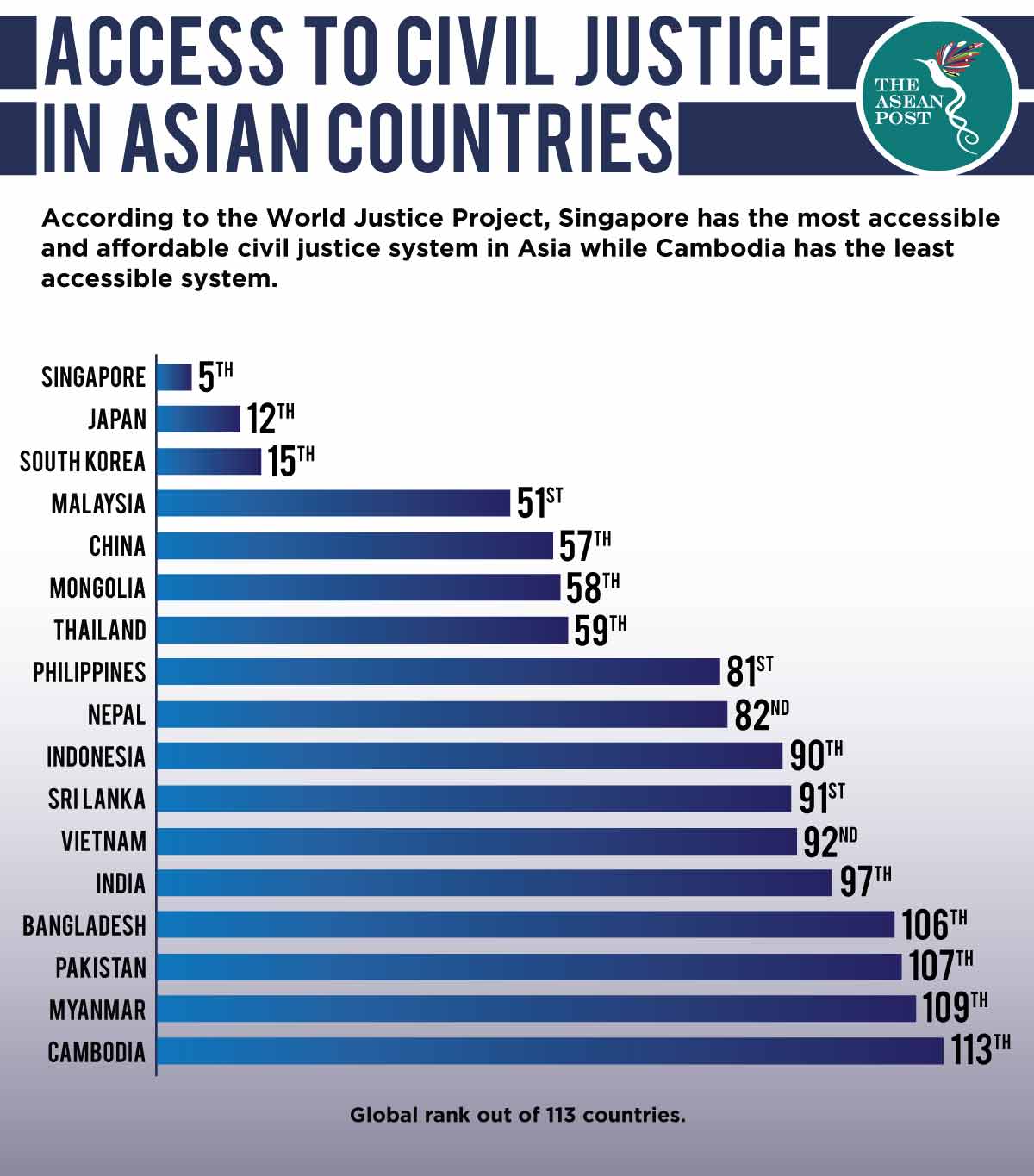

The judicial systems in these countries have weak processes to defend and protect women as well as men against sexual misconduct. Daring to speak out in some of these deeply patriarchal societies comes with enormous risks, which leave perpetrators to walk free and target their next victim.

Related articles: