There is a growing interest in organic produce in Southeast Asia. In reaction to rapidly changing farming practices, organic farming is an alternative agricultural system that strives for sustainability, the enhancement of soil fertility and biological diversity. The farming method of rotating crops and applying mulch to empty fields can stabilise soils and improve water retention.

According to the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM), organic agriculture is much more than just a way to treat soil and plants naturally – it is a holistic paradigm for sustaining life on earth. Organic farming has the potential to contribute to sustainable food security by improving nutrition intake and sustaining livelihoods in rural areas, while simultaneously reducing vulnerability to climate change.

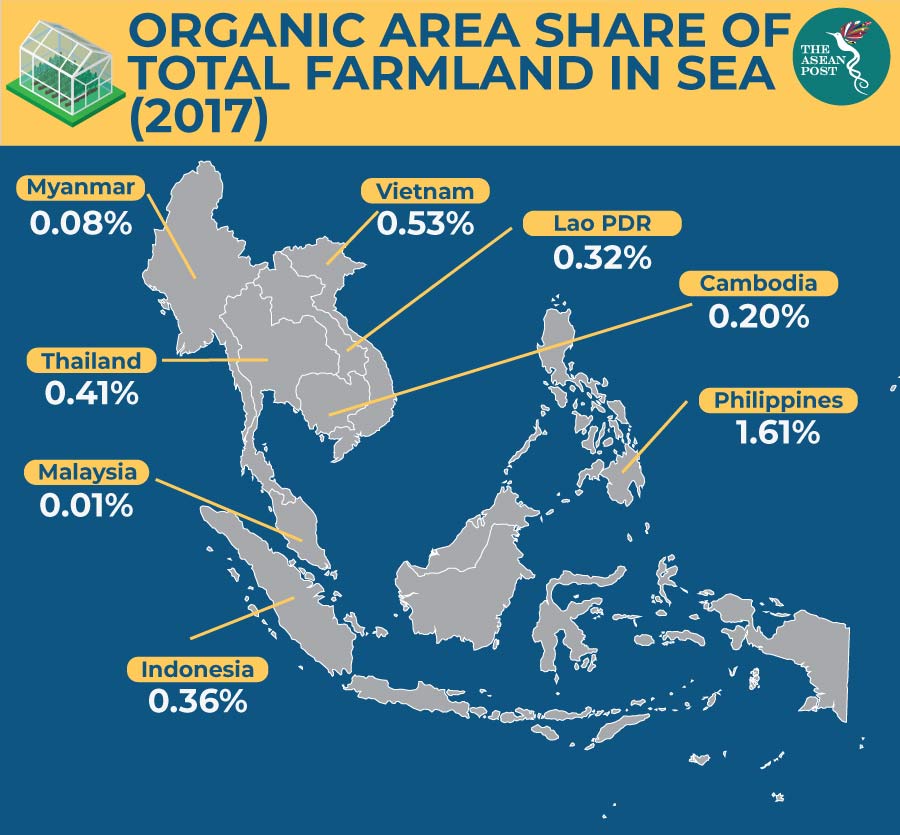

Based on data by the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), an independent institute focusing on organic agriculture, the area of organic agricultural land in Asia is almost 6.1 million hectares or 0.4 percent of the total agricultural sector in the region. The Philippines had the largest organic coconut area, with nearly 150,000 hectares, representing 70 percent of the total organic coconut area of the region while most of the organic coffee is grown in Indonesia, with over 46,000 hectares.

According to the institute, more land is going to organic farming, and the revenue created by organic food products continues to increase in many countries.

Organic agriculture

Southeast Asian farmers have realised the sustainable benefits of organic farming, including increased income, and safer and healthier food for the community.

According to IFOAM’s data, the Philippines ranked fifth on the list of countries with the largest number of organic producers (165,958). The high adoption of organic farming among Philippines’ farmers may be due to the government’s mandate, the Organic Act, which was passed in 2010. The Act was “to promote, develop further and implement the practice of organic agriculture in the Philippines,” paving the way for people to be more informed on the benefits of chemical-free agricultural products.

Judith Bopp’s 2017 article, ‘New strategies of sustainable food production in ASEAN’ for Heinrich Boll Stiftung, stated that a great part of the demand for organic food originates from urbanites’ missing options to grow or to have control over their food.

In Thailand, the Institute for Sustainable Agricultural Communities (ISAC) was established to promote organic farming and to encourage sustainable agriculture. Thailand’s target via the National Plan for Organic Farming is to attain 208,000 hectares of organically farmed land, by 2021. Its other goal is to have at least 40 percent of produce from these farmlands to be consumed domestically.

Hub for organic produce

Johor Green is a Malaysia-based social enterprise focused on a sustainable urban lifestyle. Chris Parry, founder of Johor Green, started the initiative as a side project, after observing the strange lifestyle of Malaysians who were “living” in malls.

Together with Medini Iskandar, a township developer, Parry developed and managed the Medini Green Parks comprising of a four-acre Edible Park and a seven-acre Heritage Forest. The edible park is a landscape and platform for cultivating a community around the current idea of sustainable food, whereas the forest is a wild landscape showcasing the local botanic heritage and re-establishing biodiversity and eco-services.

Parry wanted to merge the idea of local food and native plants with the local context.

“I’m interested in this concept of food sovereignty. I don’t think we have a food security problem here because we still have access to food and a lot of food is grown here. The problem is people are eating the wrong food. So that is food sovereignty, where someone comes in and affects your culture in such a way that you change your mind about what you are supposed to be eating,” he said.

Johor Green has “a program to suggest an alternative” from the unhealthy diet of Malaysians to a more plant-based diet. “Our farm sells organic produce, and our vendors are doing artisanal food, which fits the idea of ‘slow food’ movement, quite the opposite to fast-food,” Parry added.

Johor Green’s edible park is a “hub for organic produce, and we also have a platform for people to knowledge share, which I think is great for urban citizens,” Parry said. The farm also holds nature classes, social gatherings, talks and workshops and also a regular farmers’ market. At the farm, people also learn how to make artisanal and heritage food.

Johor Green’s farmers’ market is also a place where communities gather and share healthy food values with their children, meet up with friends for a meal and connect with others through food and education. Being centrally located in an urban environment is advantageous for a neighbourhood market.

Organic farming has proven to be a sustainable way of bringing balance to all things living – it is a movement that can empower both, farmers and consumers. As the demand for organic food in Southeast Asia continues to grow, it is still uncertain whether the supply of local organic produce can keep up with the ever-increasing demand.

Related articles: