Last month, media freedom advocates praised the surprise release of two Reuters reporters in Myanmar but stressed the pair should never have been jailed in the first place. They called for sweeping reforms of the country’s paralysing press laws.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning reporters walked free from Yangon's Insein Prison after more than 500 days behind bars as part of a large presidential amnesty following a global campaign calling for their release.

Several months prior, in January, the military in Myanmar, also known as the Tatmadaw, had threatened legal action against media organisations found to have reported unverified stories involving security issues and armed conflicts. Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Commander-in-Chief of the Myanmar Armed Forces alleged that some news organisations had reported unverified stories about armed conflicts.

Local media noted that the Tatmadaw was apparently upset about recent reports that fighting had erupted between government forces and northern armed ethnic groups. The report had come in just hours after the Tatmadaw had issued a statement declaring a four-month unilateral ceasefire in parts of the country to boost the peace process.

Senior General Min said that news about the military should be published only after being verified with the ministers for Security and Border Affairs and General Staff colonels of military commands. The Tatmadaw also expressed concern as the reports came from unreliable sources and not from the government. The concern was that it could potentially harm the ongoing peace process.

There are certainly dangers to reporting falsehoods as is apparent in other parts of the world including India where fake news has led to numerous lynching incidents. But where is the line drawn between allowing only news which paints those in power in a good light and controlling the spread of falsehood?

Inspiring confidence

The problem, in the case of Myanmar, is that the country doesn’t exactly inspire confidence in its treatment of journalists. This was especially apparent in the case involving the two Reuters journalists, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, who were arrested in December 2017 for allegedly accepting secret documents from the police in connection to a story they were working on. Had they been convicted under the Official Secrets Act – a colonial law implemented during the British occupation of Myanmar – the two journalists could have faced up to 14 years in jail.

Prior to the arrests, the two journalists were working on a story about 10 Rohingya Muslim men and boys who were killed in western Myanmar’s Rakhine state. The story based on their findings was eventually published by Reuters in February last year.

The Myanmar government denied claims that the two journalists were arrested because of their investigations, insisting that they were arrested under the Official Secrets Act. However, the testimonies heard in court say otherwise.

The testimony by Police Captain Moe Yan Naing revealed that a superior had arranged for two policemen to entrap Wa Lone by offering him “secret documents” and then arresting him. This contradicts the prosecution’s story that Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo were arrested at a routine traffic stop and found to be in possession of secret documents.

In his testimony, Wa Lone claimed that the police didn’t even focus on the secret documents.

“During the whole interrogation, they didn’t ask with interest about the secret documents found on us, but they probed us about our reporting of Maungdaw, Rakhine,” Wa Lone told the court.

The odd behaviour of the Myanmar government in relation to the case had also raised more suspicions. After Captain Moe Yan Naing revealed that the police received orders to entrap the two journalists, his family was ordered to move out of their police housing unit. If found guilty of violating Myanmar’s Police Disciplinary Act, Captain Moe could be sentenced up to a year in prison.

Unfree press

It’s no secret that Southeast Asian countries in general are struggling in terms of fostering and nurturing freedom of the press. Myanmar, is certainly no exception.

According to the 2018 World Press Freedom Index, Myanmar was placed third in ASEAN for press freedom. While third place may not seem all that bad, considering the terrible state of press freedom in the country, the bronze medal is nothing to shout about.

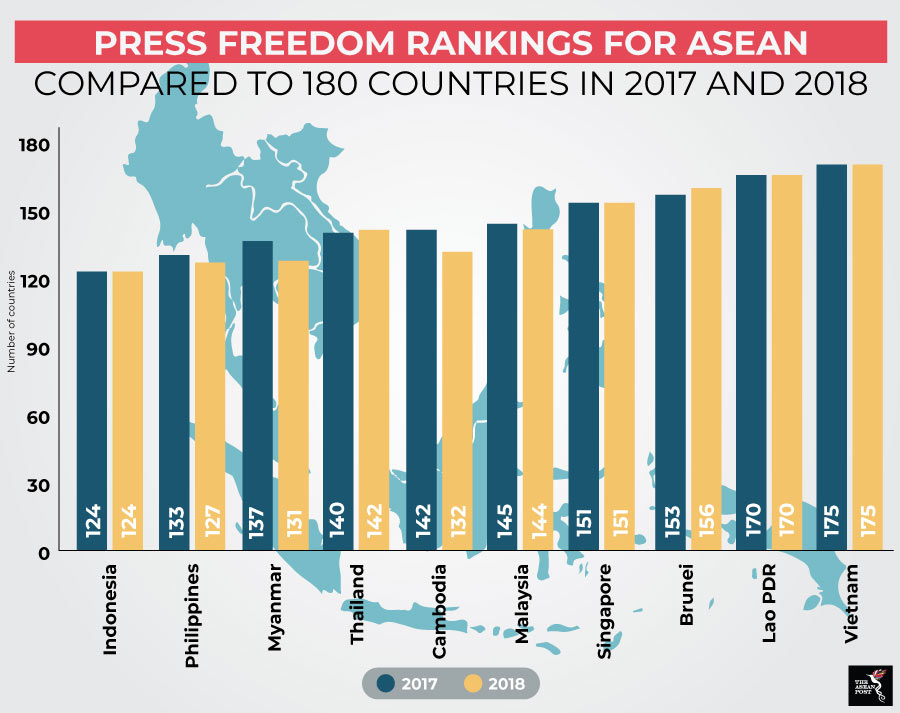

Based on a sample size of 180 countries, Indonesia, Singapore, Lao PDR, and Vietnam have maintained their positions at 124, 151, 170 and 175, respectively. Vietnam is adjudged to have the least amount of press freedom in ASEAN while Indonesia has the most. Countries that saw improvements in press freedom were the Philippines which moved up the ladder from 133 to 127, Myanmar from 137 to 131, Cambodia from 142 to 132, and Malaysia from 145 to 144.

Myanmar may have released the two Reuters journalists, but that does not mean that there isn’t a very real likelihood of other journalists getting themselves arrested for merely doing their jobs in the future. The hope is that the release of the two Reuters journalists will serve as a catalyst for greater press freedom in the country.

Related articles: