Rohingya refugees fleeing anti-Muslim persecution in Myanmar are being exploited by the Arakan Army to smuggle synthetic drugs into Bangladesh. The army, which is demanding greater autonomy for Myanmar’s Rakhine State, uses money from the drug sales to purchase arms and ammunition. It moves the drugs from production centres in Myanmar’s interior to Rakhine State, where the Rohingya make the arduous trek along refugee migration routes into neighbouring Bangladesh. Lacking other sources of income, the Rohingya are vulnerable to recruitment by the army’s drug smugglers.

A Vulnerable People

Having lost family, friends, and most of their possessions during military crackdowns in Myanmar, the Rohingya find themselves in overcrowded refugee camps with few resources at their disposal. Poverty and restrictions on employment in refugee camps in Bangladesh make it difficult for the Rohingya to support themselves and their families. As highlighted in the Stable Seas: Bay of Bengal maritime security report, limited resources can trigger secondary migrations or push refugees into engaging in illicit activities. Despite the risks, drug smuggling offers an enticing prospect as it provides money for basic necessities like better rations and healthcare. Between 2017 and 2018, authorities arrested more than 100 Rohingya crossing the border into Bangladesh on drug trafficking charges.

Overlaps between drug smuggling routes and Rohingya migration routes have far-reaching repercussions for the livelihoods of the Rohingya. The links between the Rohingya and the drug trade have led to increased sanctions against refugee rights, including denied access to mobile phone services and rules that limit the movement of the Rohingya outside refugee camps. Bangladesh also instituted the Narcotics Control Act 2018, which created a maximum punishment of the death penalty for producing, smuggling, or distributing more than five grams of amphetamine-based products. Between the response of the Bangladeshi government and an inevitable upsurge in addiction rates in refugee camps, the drug trade has directly affected the lives of Rohingya refugees.

Drug Production

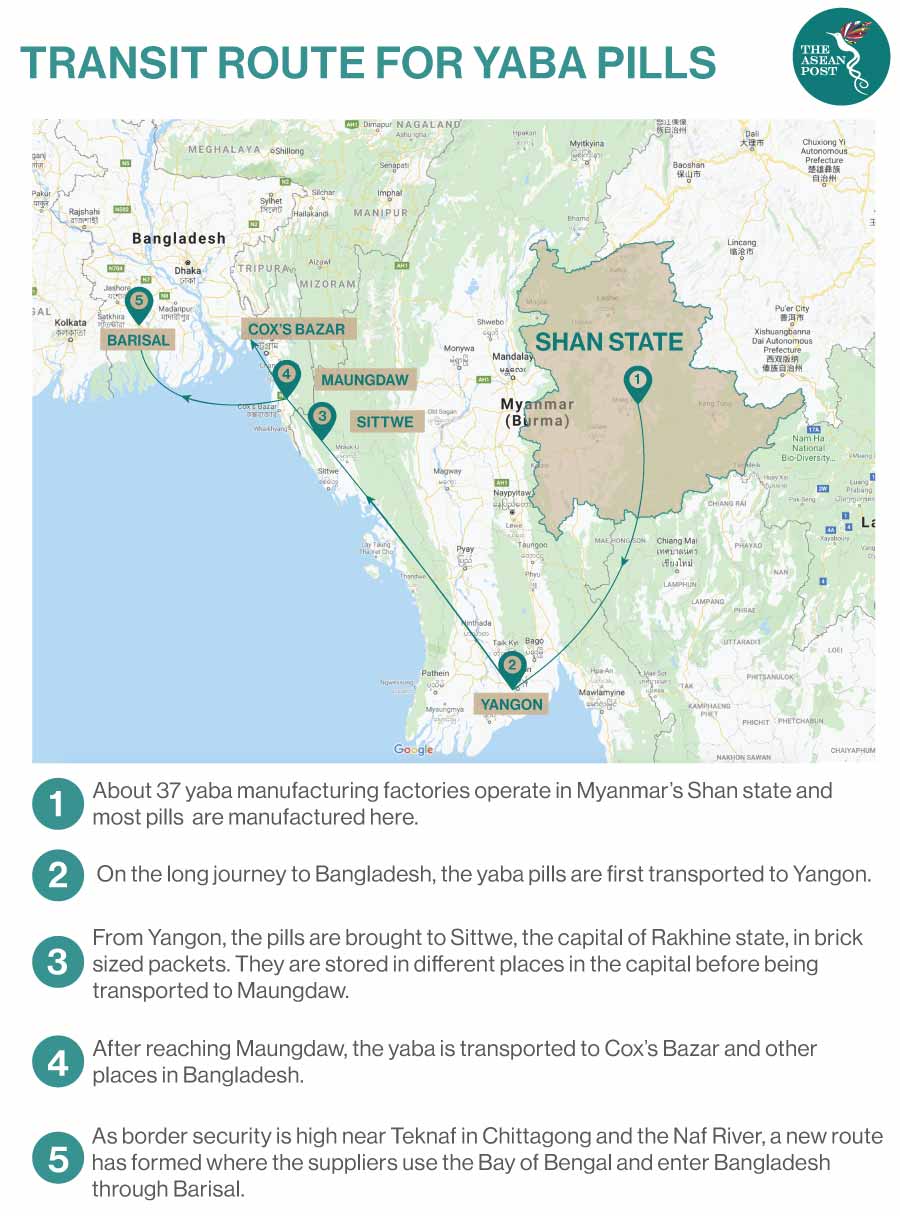

The Arakan Army’s drug trade is an extensive operation stretching from Shan State in Myanmar’s interior to urban centres in Bangladesh. Shan State has proven to be a major production centre for illicit synthetic drugs. In January 2018, government forces conducted a raid in the Shan State’s Kutkai township and seized 30 million yaba pills, 1,750 kilograms (kg) of crystal meth, 500 kg of heroin, and 200 kg of caffeine powder. Yaba is a popular and highly addictive stimulant that consists primarily of caffeine and methamphetamine. According to authorities, the drugs seized were valued at roughly US$54 million, making the drug bust the largest in Myanmar’s history.

The Arakan Army uses its strong relationships with armed ethnic groups based in Shan State to access the state’s drug production centres. In August 2019, the insurgents launched a series of coordinated attacks in Shan State with two other ethnic armed groups. According to the Myanmar Army, the attacks, which included raids on narcotics control checkpoints, were in retaliation for government raids on drug production facilities in Shan State. By leveraging its connection to armed ethnic groups in Shan State already involved in the drug trade, the Arakan Army taps into existing smuggling networks and production centres.

Smuggling Routes

The Arakan Army transports the drugs from Shan State west via Rakhine State to markets in Bangladesh. In 2018, officials seized around 6.96 million Yaba pills in Rakhine State within a period of only three and a half months. The location of drug seizures suggests the group transport the drugs primarily by boat and road through the northern Rakhine State town of Maungdaw before either crossing the Mayu mountain range or the Naf River into Bangladesh. The drugs also reach the shores of Teknaf in the southernmost end of Bangladesh by boat before being transported inland.

Although the Arakan Army has officially denied involvement in the drug industry, arrests of its members, combined with an uptick in Rakhine State drug seizures, suggest otherwise. The group’s members, including Arakan Army Officer Aung Myat Kyaw, drug smuggler U Wai Tha Tun, and former Administrator U Kyaw Myint, have all confessed to smuggling drugs for the Arakan Army. Myint alone allegedly used drug trafficking to raise an estimated US$299,000 to illicitly procure arms for the group.

Once the Arakan Army succeeds in transporting the synthetic drugs into Rakhine State, they recruit the stateless Rohingya to smuggle the merchandise into Bangladesh, which has responded by increasing refugee restrictions. The sanctions, however, have not proven effective and lower the standards of living in refugee camps already plagued by unsanitary living conditions, poor healthcare, and lack of economic opportunity. What’s more, not only do the Rohingya risk the death penalty, their participation in the drug trade could jeopardise the refugee status of all Rohingya in Bangladesh as public pressure to address drug proliferation mounts.

Without international pressure on Myanmar’s military to crack down on synthetic drug supply routes and production centres, the Arakan Army’s drug trade will continue to flourish at the expense of the Rohingya.

This article was first published on 25 May, 2020 in New Security Beat.

Related Articles: