“It started in 1998. It peaked 10 years later in 2008. And it has not stopped changing. Changes are still ongoing even as you read this. It is now unstoppable. The government can no longer turn back the tide. Malaysians are moving forward and the way forward is a Malaysia with no more racism, a Malaysia that recognises human rights, a Malaysia that respects free speech, a Malaysia that gets dragged – screaming and kicking – into the new Millennium.”

While prominent Malaysian blogger Raja Petra Kamarudin was perhaps buoyed by the results of the 2008 Malaysian general election – when the ruling National Front (Barisan Nasional) suffered its worst electoral defeat – when writing the above paragraph in his 2009 book The Silent Roar: A decade of change; it seems that the changes he called for all those years ago have yet to fully materialise.

The “screaming and kicking” part might have been on point though.

Take for example the abduction of activist Amri Che Mat and pastor Raymond Koh – the former in 2016 and the latter in 2017 – both of whom have yet to be found. Their disappearances have received wide media coverage, especially since the duo were allegedly involved in the propagation of Shia and Christian religious teachings. Also missing are the couple of Joshua and Ruth Hilmy, pastors who have not been seen since 2016.

After an extensive investigation, reports by the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) released on 3 April concluded that the Malaysian police’s Special Branch was involved in Amri and Koh’s abduction – going so far as to describe it as an “enforced disappearance by state agents”.

On Wednesday, Malaysia’s Home Minister Muhyiddin Yassin said the Cabinet had given the green light to create a task force to look into the matter.

Slow to react

While both disappearances happened under the watch of the previous National Front government, the fact that the current Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan) coalition-led government has hardly addressed the matter since coming to power last May has raised questions about its commitment to human rights – especially after promising in its election manifesto to make Malaysia’s human rights record “respected across the world”.

It’s manifesto also promised to make Suhakam “a body that is highly-regarded and respected”, raising eyebrows as to why the government did not choose to follow Suhakam’s recommendation to set up the task force when the reports were first published.

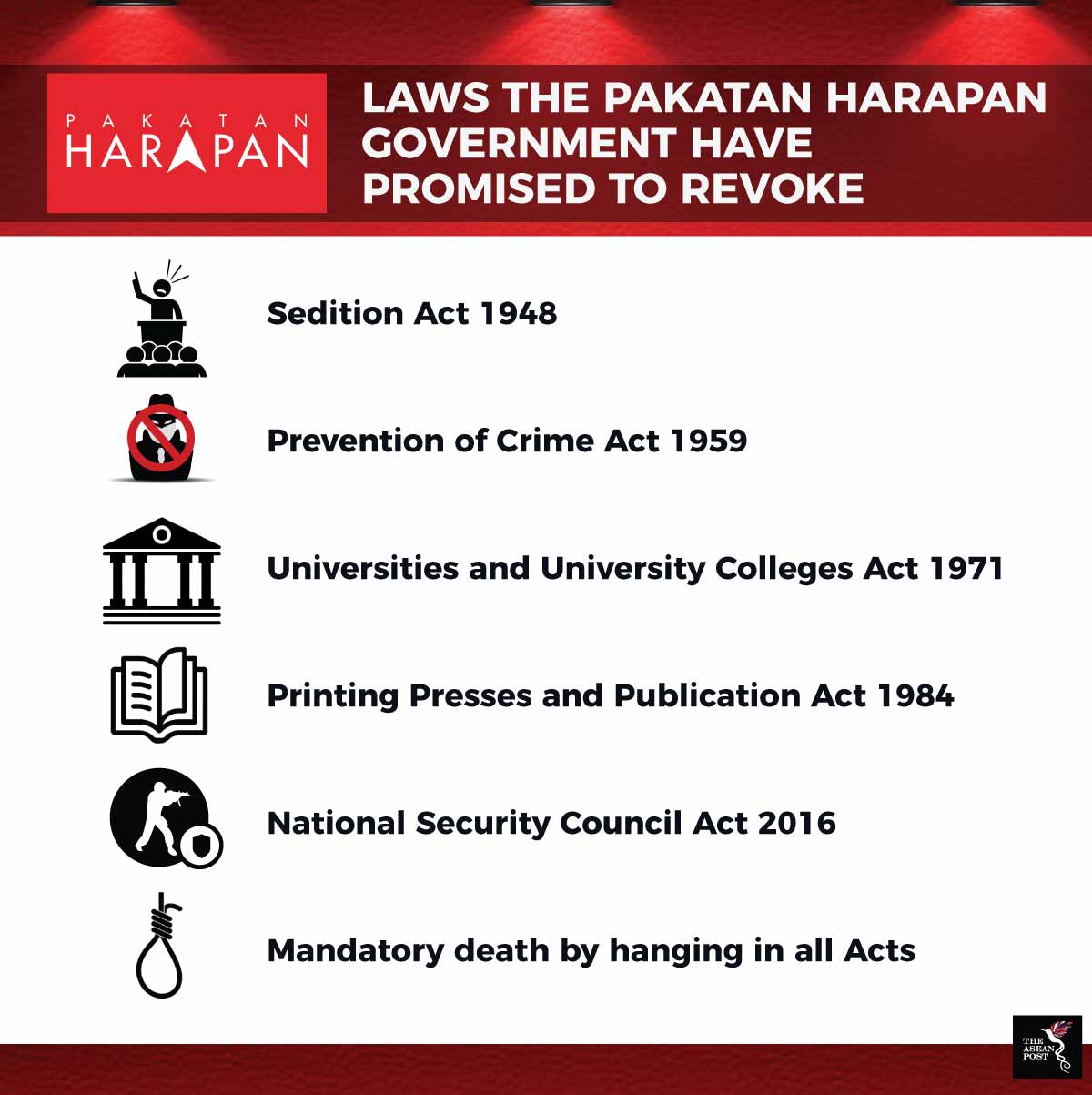

Several other laws enacted by the previous government which it deemed “tyrannical” are also yet to be revoked as promised – although issues such as not possessing a two-thirds majority in Parliament to amend or repeal these laws have also played a part in this.

Human Rights Watch concerned

After the reports by Suhakam – an entity established by Parliament under the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia Act 1999 – were made public, human rights advocacy group Human Rights Watch also joined the chorus of voices calling for intensified investigations.

While saying that Suhakam’s allegation that the Special Branch was involved in the duo’s disappearance was “merely hearsay”, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad told the media that investigations into the two cases would begin after a new Inspector-General of Police (IGP) was appointed. After all, the IGP at the time (Mohamad Fuzi Harun) headed the Special Branch when both disappearances occurred – and he was set to retire on 2 May.

In a letter to Mahathir on 3 May – the same day new IGP Abdul Hamid Bador took office – Human Rights Watch’s Deputy Asia Director Phil Robertson encouraged the government to “establish an independent Special Task Force to investigate these enforced disappearances and to ensure all police officers implicated in these enforced disappearances, regardless of position or rank, are held accountable for their actions.”

“The actions of your government to pursue accountability and justice, and to ascertain the fate of Amri Che Mat and Raymond Koh, will be an important indicator of your government’s commitment to rights-respecting reforms,” wrote Robertson.

Police transparency

While Abdul Hamid said he has yet to be briefed about the task force, he takes up the post with an already strong reputation for accountability and transparency.

He has agreed to the formation of the Independent Police Complaints and Misconduct Commission (IPCMC), one of the promises the Alliance of Hope coalition made in its election campaign manifesto, and has started investigating officers alleged to have taken bribes and those with links to criminal syndicates.

Weary of the previous government’s corruption and mismanagement, the people of Malaysia voted out the National Front and backed the Alliance of Hope. It is these same people who will make sure the new government stands behind their election promises – especially on such crucial matters as human rights and enforced disappearances which have eroded the public’s trust in the police.

As Raja Petra wrote in his book; “The peoples’ wrath will see to it that changes will occur at whatever costs.”

Related articles:

The Doctor is back. Can Malaysia be cured?