A smart city is an urban area that uses technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and big data to efficiently manage its assets, ultimately enhancing its residents’ quality of life.

Reduced congestion, pollution control and better energy efficiency are just some of the many advantages of living in a smart city – and ASEAN has 26 of them now under its ASEAN Smart Cities Network (ASCN) pilot cities initiative.

But as appealing as better air quality and less traffic jams may be to the region’s rising urban population, footing the bill for all these improvements is a less popular subject.

It is often left to city councils to pick up the expense, and for many, the cost of setting up and maintaining an expensive array of sensors and monitors – and the staff to operate them – is simply too prohibitive.

“Much promotion of smart cities assumes that municipalities will take a proactive, top-down, technology-first approach to urban progress,” explained John D. Macomber, Senior Lecturer of Business Administration at Harvard Business School.

“Thus far, these initiatives look for some forward-thinking city official (or immensely deep-pocketed private investor) to write a big purchase order for a lot of hardware and software,” he added, calling for public-private partnerships (PPPs) to lead the way in smart city development.

Public-private partnerships

At the ASEAN Smart Cities Network Roundtable Meeting in Bangkok in June, Thailand’s Digital Economy and Society Minister Pichet Durongkaveroj called for more PPPs and said his country plans to attract non-ASEAN countries for partnerships and investments in smart city infrastructure as part of the ASCN.

Among the countries mentioned were Japan, South Korea and China – all nations with extensive capabilities and expertise in new technologies and ones which ASEAN has already worked with in transfer of technologies.

In August, the ASEAN Smart Cities Network Conference & Exhibition 2019 – also in Bangkok – held a series of seminars, one of which was titled ‘Ultimate Driving Forces: Reengineering Public-Private Partnership’.

The seminar focused on the possibilities that lie ahead if urban planning and smart city development are driven responsibly and sustainably by the comprehensive collaboration of state agencies and business sector PPPs, the latter of which is expected to become the ultimate driving force behind building smart cities in the region.

As the ASCN’s concept paper noted, the network aims to “catalyse bankable projects with the private sector” and to “secure funding and support from ASEAN’s external partners.”

No mention is made of the city councils or municipal boards who are the owners and operators of these smart technologies – and who are ultimately left with the responsibility of maintaining and thinking of a way to create a revenue stream from them.

Capital cost

In his thesis for his Master of Civil Engineering degree at the University of Delaware last year, Xiong Xiangyuan wrote about the complexities in monetising the various aspects of improvement derived from smart city technologies – and how high costs are a put off for investors.

Titled ‘Cost-benefit analysis of Smart Cities technologies and applications’, the thesis outlined benefits ranging from reduced travel time, less fuel and energy consumption, lower gas emission and greenhouse gas and less noise which have to be balanced with variable costs such as capital, maintenance and operation.

Missing infrastructure, cyber security costs, advertising fees, noise impact from construction and labour cost within the project lifetime were also highlighted as key considerations prior to introducing smart technologies.

However, capital costs – the one-time expense of planning, acquiring land, engineering design, purchasing equipment, constructing and ensuring regulations are adhered to during each step of the way – was found to be the main hurdle in getting smart cities off the ground.

“According to those prosperous smart cities, the capital cost is expensive indeed, but the benefit and advantages are also considerable,” he noted.

“With the recognition of the high capital cost of smart cities, the city decision makers know it is not easy to start smart cities projects without reliable financing sources,” he added.

Potential for savings

It is undeniable that there is huge potential for savings if smart technologies are implemented.

Barcelona saved more than 75 million euros (US$82 million) after using IoT-driven technologies in its utilities in 2014, and Intel has estimated that reductions in traffic and congestion would contribute to savings of up to 125 hours a year.

“City councils in particular, who are often strapped for cash, can benefit massively from investing in smart city technologies – seeing both immediate and long-term cost savings that allow them to increase their budgets in other crucial areas of work – such as social welfare,” said Dr Alexander Gelsin, Managing Partner at bee smart city, a platform which promotes smart city development.

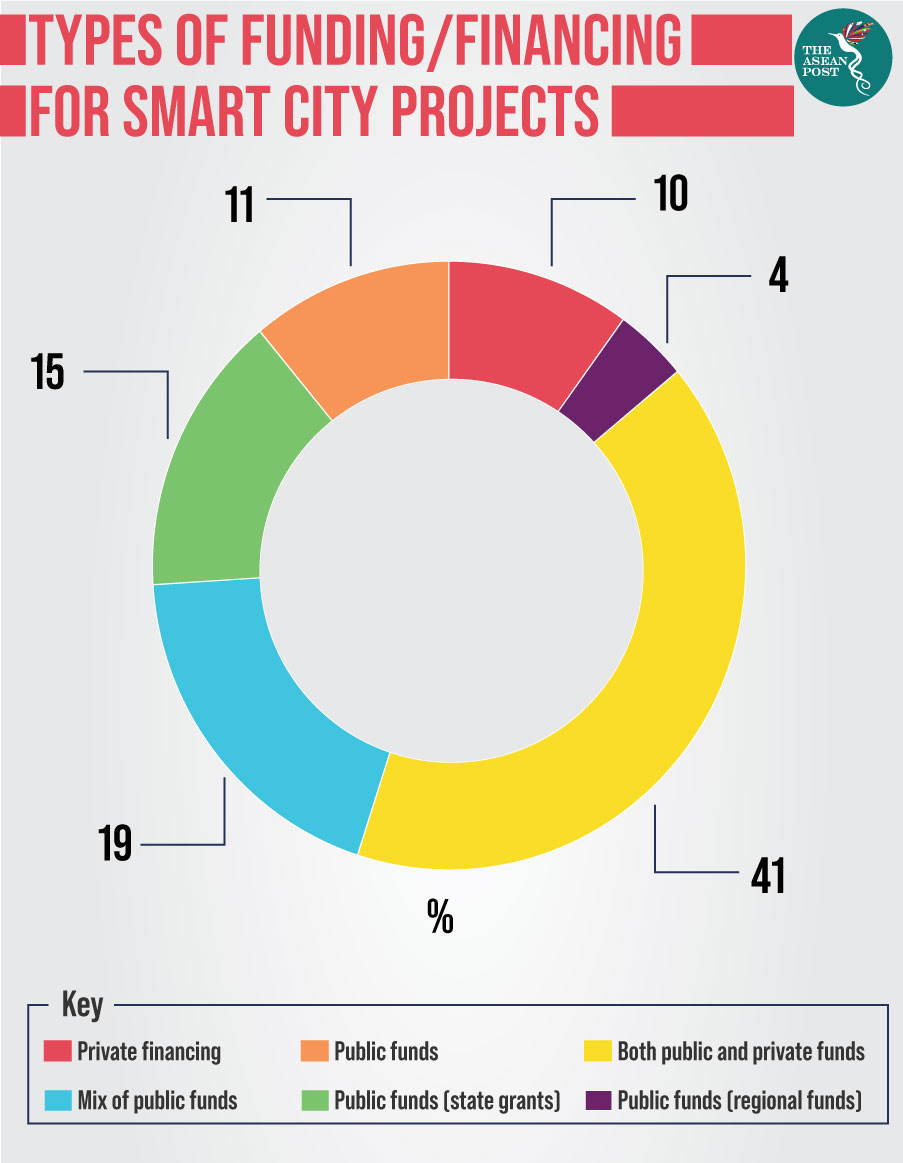

However, before cities look to improve their infrastructure with smart technologies on a wide-scale basis, they have to get over the challenge of paying for these projects and identifying sustainable and profitable business models.

Related articles:

Welcome to the future: ASEAN Smart Cities Network