The Philippines is likely to be able to fund its Build, Build, Build infrastructure project (2016-2020) under its 10-point Socio-Economic Agenda, but it may face setbacks in terms of labour to make it happen.

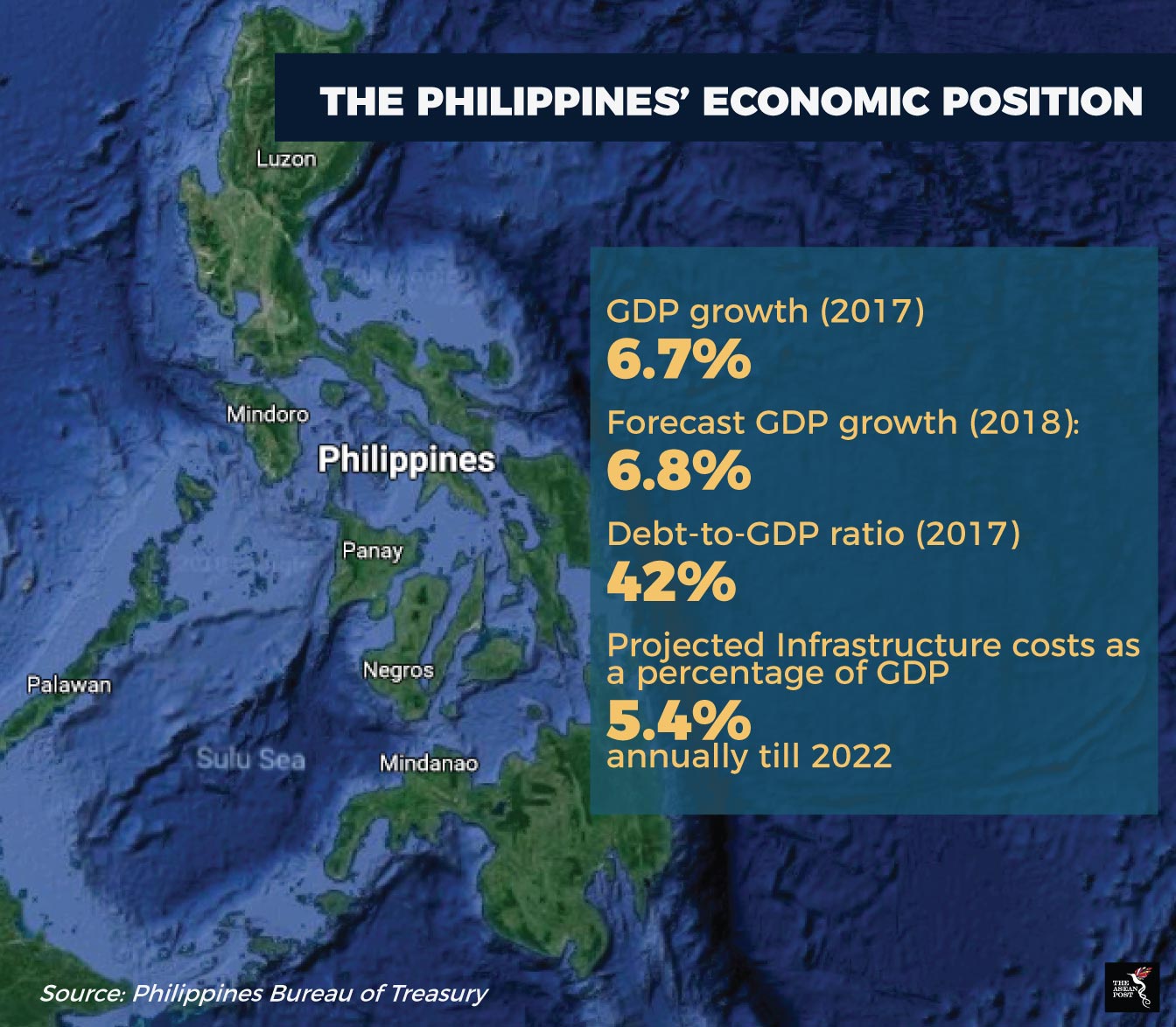

GDP growth for the Philippines' was recorded at 6.7% last year, according to Moody's Analytics and larger spending on infrastructure, will help it to sustain long term growth. According to the World Economics Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018, the Philippines’ ranking fell two notches to 97th placing because of its infrastructure. It is believed that improving its ports, roads, airports and railroads would help address revenue loss of up to PHP3 billion a day due to traffic congestion, according to a study by the Japan International Cooperation Agency. Implementing large construction projects would also double the amount of new jobs created per year, from the current one million jobs created to two million jobs created annually, according to Ernesto Pernia, National Economic & Development Authority (NEDA) chief.

“The flagship infrastructure projects under the ‘Build, Build, Build’ program will spur economic growth and improve people’s living standards. Better infrastructure will lower the cost of doing business, shorten travel times, and usher in more economic opportunities in remote areas. It will also make it easier for people to access education, healthcare, and other social services,” said Richard Bolt, ADB Country Director for the Philippines last year.

Projects and financing

The 75 infrastructure projects in the pipeline under Build, Build, Build are expected to cost between US$160-180 billion in total between 2017 and 2022, according to the Asian Development Bank. Compared to infrastructure spending by previous administrations, which had only amounted to about 2.6% of GDP, approved projects so far already take up a budget allocation of 5.4% of GDP, according to budget secretary Benjamin E Diokno, who spoke at a ‘Dutertenomics’ forum in Manila last year. The forum highlighted some of the infrastructure projects that were in the pipeline for development under the Build, Build, Build, policy. 53 of these projects have been valued at US$31 billion, according to NEDA data. The value of the other 22 projects remains to be confirmed.

The government has so far indicated that it would finance its infrastructure projects through a combination of national tax reforms, foreign loans and grants from abroad, reforms to Philippine capital markets and public-private partnerships, according to the 2017 report by the United Nations Economic & Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific.

Approved projects so far include the Mega Manila Subway, a 25.3-kilometer underground rail network connecting Quezon City and Taguig City. The project, initially worth US$7 billion will be funded by Japan and is scheduled to begin phase one development next year. The Philippines government will sign a memorandum of understanding with Japan covering the first tranche, which amounts to US$929.1 million soon after the Philippines obtains Monetary Board approval, according to its Department of Finance recently.

Japan and China have each pledged US$9 billion in loans and grants to the Philippines’ infrastructure projects, according to Bloomberg data. Financial assistance will also be obtained from the Asian Development Bank, which has pledged loans of up to US$3.68 billion between 2018 and 2020 for commencement of the Malolos-Clark Railway Project in 2019 worth PHP211.42 billion and to build an extension to its North-South Commuter Rail System for PHP299.4 billion.

The Philippines government’s tax reforms in December 2017 would add up to US$1.78 billion to its reserves, according to Carlos Dominguez, Philippines Finance Secretary. Provisions include increased excise taxes on petroleum, coal, cars, cosmetic surgery procedures and sugar-sweetened beverages. Individual income taxes were however reduced.

Other infrastructure projects approved last year include road expansions in southern Philippines (PHP21.2 billion), the construction of bridges in Manila (PHP6 billion), irrigation system improvements (PHP3.5 billion), and a new terminal at Clark International Airport (PHP12-15 billion), according to Reuters reports.

One of the key concerns critics have expressed is whether Duterte can afford taking such loans without incurring deep foreign debt in the long run. Dominguez says debt as a percentage of GDP is currently on steady decline. The previous administration’s tight fiscal policy managed to shrink its debt-to-GDP ratio to just 42% from about 52% in 2012, according to the Philippines’ Bureau of Treasury.

“The Philippines can afford to borrow,” said Euben Paraceulles, an economist with Singapore’s Nomura Holdings Inc. While he believes this is possible for the next two years, he cannot say the same for the period beyond that.

Even if the Philippines can afford to fund its grand infrastructure plans, it would still need to address accompanying issues such as the red tape before foreign funds can be approved and a lack of construction labour. The BMI labour market index showed scores of just 51.8 out of 100 for the Philippines, alongside Malaysia’s 58.3, Thailand’s 58.2 and Singapore’s 74.9. This index calculates the availability, costs and skill levels associated with labour. The gap between skills and labour availability is attributable to large numbers of workers leaving the Philippines each year.

Perhaps an attractive repatriation program could be the long-term answer to the country’s labour shortage woes.

“The labour shortage is an issue that’s hounding the construction industry,” said Jan Paul Custudio, senior director at property consultant Santos Knight Frank in Manila.

One thing is certain, as the Duterte administration embarks on its ambitious infrastructure push, the success or failure of it may rest not so much on funding but a quick solution to its skilled labour shortage woes.

Recommended stories:

Are Facebook & Google getting too big for us?

What the global economic recovery means for ASEAN

How will the CPTPP pan out for ASEAN?