Surrounded by severely damaged coral reefs, the fishers of Indonesia’s Seraya Besar, off the west coast of Flores, struggle to make ends meet. Year-on-year fish stocks have shrivelled as the damaged reef can only support limited life. If these fishers want more, they would have to fish further out, increasing their costs and lowering profits.

Armed with memories of larger catches and bigger fish within their local waters, the fishers of Seraya Besar, in partnership with a French non-profit reef conservation organisation Coral Guardian, came together to set up a locally managed marine protected area (MPA). Manned by a 15-person team, the damaged coral reefs within the 1,550-acre MPA underwent small-scale coral restoration, under which more than 26,000 corals were planted.

According to a report by the Ocean Agency, the outcome resulted in boosted fish stocks including protected species with five-fold hauls described by fishers. Over the past two years, the coral plantings have grown to form a natural-like reef, with the steel structure barely visible. Bigger fish like groupers, trigger and butterflyfish have also been seen taking occupancy.

Within the MPA where corals have been planted, the numbers of fish have grown from 200 fish per 100 square metres to roughly 1,000 fish per 100 square metres. The impact spill-over on human livelihood can also be felt in much wider areas, including on the nearby Komodo National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Politically-motivated, scientifically-based MPA

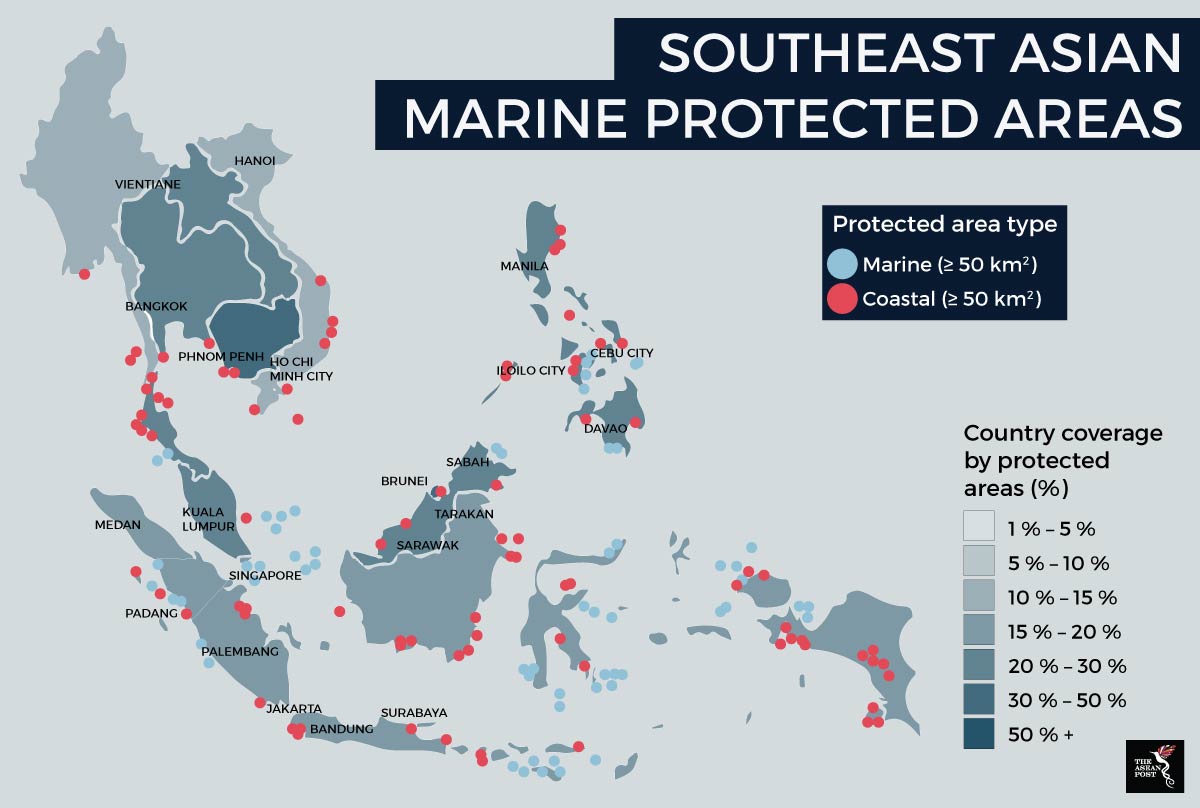

MPAs are one of the instruments used to protect our coasts, estuaries and seas of particular scientific interest or with high biodiversity within local, national or international law from damaging human activities. The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 on life under water targets a 10 percent share of MPAs by 2020. Questions have been raised on how these areas are selected and if quotas are filled for the sake of achieving targets and not based on achieving conservation benefits.

Source: European Union Digital Observatory for Protected Areas (DOPA) Explorer.

The United Nations (UN) Special Envoy for the Ocean, Peter Thomson, said that while the current determination of MPAs are both, political and scientific, governments need to do more to back their actions scientifically. According to Thomson, two big things need to happen to achieve this objective: increase MPAs well beyond 10 percent and improve their quality in terms of management and enforcement policies.

“We have to protect coastal areas, but also remote areas. We need to protect the Arctic and the Antarctic. A year ago, we were at 5.7 percent, today we are at 7.4 percent. 10 percent is definitely achievable. But we have to look beyond the 10 percent. It will not just stop after 2020. The challenge is going to be to connect all these protected areas in scientifically correct ways.

“After 2020, we have the UN Decade of Ocean Science. I would expect that during that decade we are going to be able to sift humanity’s knowledge of the science of the ocean and that will much better equip us working out what part of the ocean should be protected,” said Thomson, who is also the Co-Chair of the Friends of Ocean Action, an initiative run by the World Economic Forum (WEF) and World Resources Institute (WRI).

Local participation key to success

For countries like Indonesia where limited support from government agencies is expected due to the territorial spread of over 17,000 islands, local participation especially from fisher communities is very important. Coral Guardian's Co-founder and Scientific Director, Martin Colognoli said that in Seraya Besar, much of the work is carried out by the village’s fisher communities.

This include construction and deployment of the concrete-iron cage structure that holds the implanted new corals, as well as the deployment of the ecological and social survey. In fact, the success of the project depends entirely on the villager’s constant role in monitoring, preventing fishing during the restoration process and boat anchoring.

“We believe that effective biodiversity protection requires the involvement of local populations, their participation in its conservation and their capacity to sustainably manage the ecosystems on which they depend,” said Colognoli.

It is key that everyone, even those in land locked countries, realise that protecting the oceans is a common responsibility. The ocean is responsible for half of the oxygen in our atmosphere. Now, our oceans need our immediate attention and our contribution to that cause is essential for the health of the oceans, the planet and its people.

Related articles: