Indonesia’s location on the Pacific ring of fire, where the Indian-Australian, Eurasian and Philippine tectonic plates meet, makes it a hotspot for earthquakes. Its disaster-prone situation is further compounded by its location in Southeast Asia, one of the most vulnerable regions to climate-related extreme events. After a season of loss, the Indonesian government is now looking at a new integrated disaster risk financing and insurance strategy to help the country finance its recovery.

Finance Minister, Sri Mulyani Indrawati, said that the strategy, adopted early October, is critical to protect public assets and to accelerate recovery in a country where disasters caused losses of around 126.7 trillion rupiah (US$8.3 billion) between 2004 and 2013. To start off, the government will begin insuring its buildings in 2019.

Currently, the disaster recovery and reconstruction costs in Indonesia rely heavily on the state budget, particularly the annual disaster contingency fund of around 3.1 trillion rupiah (US$203.7 million) from 2005 to 2017. However, National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB) spokesman, Sutopo Purwo Nugroho, has described the amount as insufficient.

Shaken and stirred

In the last couple of months alone, Indonesia has been on the front pages of the world’s media, with reports of one disaster after another. On 29 July, a magnitude 6.4 earthquake shook the Indonesian island of Lombok, killing 20 and injuring hundreds. This was followed by a 7.0 magnitude earthquake a week later, which killed more than 500 people and caused widespread damage on the tourist island and on nearby Bali.

Two months later, on 28 September, a magnitude 7.5 earthquake and triggered tsunami devastated the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. The double blow that destroyed most of Palu, Donggala and Sigi killed over 2,200 people and displaced more than 220,000. Thousands more are still missing and presumed dead.

The damages to Lombok are estimated at more than US$500 million, not including the long-term paralysis experienced by the island’s tourism sector. In Sulawesi, preliminary damage estimated by the World Bank put the costs of physical loss involving infrastructure, residential and non-residential properties at around US$531 million. This assessment does not account for loss of life, lost land or disruption to the economy.

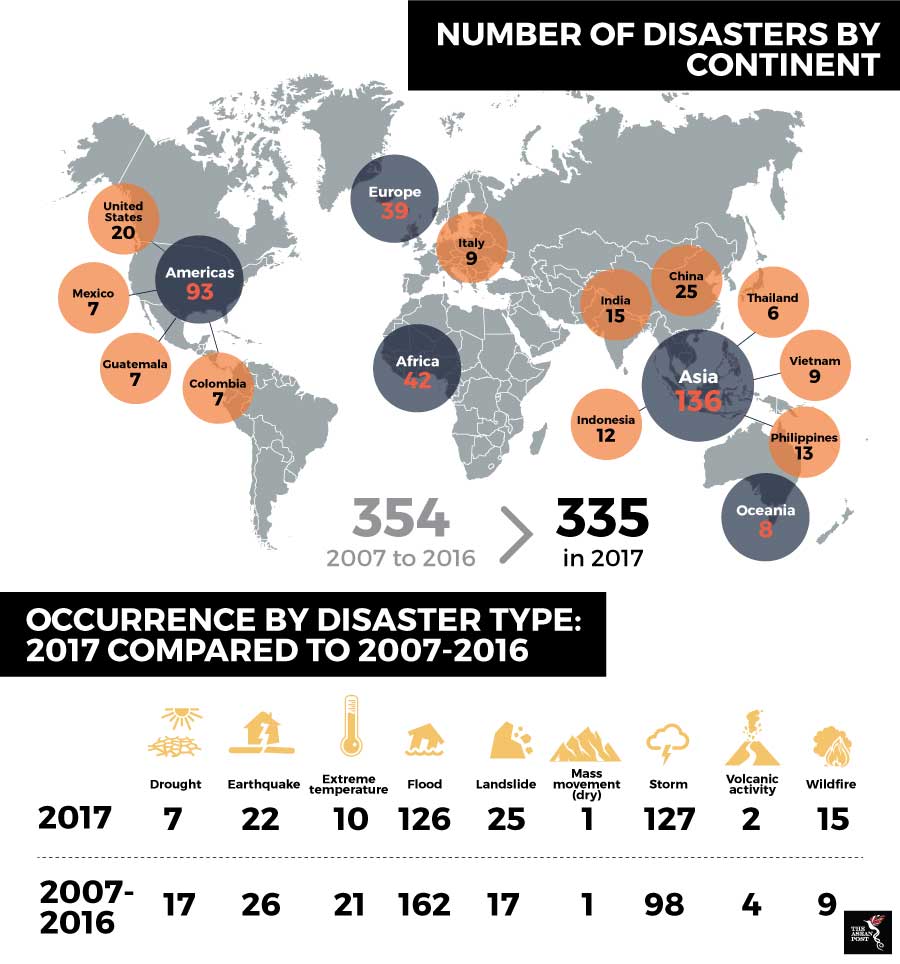

Source: Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters.

Cat bonds for Indonesia’s disaster financing

One of the risk mitigation instruments considered by the Indonesian government is catastrophe (Cat) bonds, currently utilised by countries such as Taiwan, Japan and Mexico. Through state-issued Cat bonds, these countries transferred their disaster risks to the capital markets, allowing the government to secure financing for their recovery and rebuilding initiatives in the event of disasters.

According to the Overseas Development Institute’s Risk and Resilience Research Fellow, Margherita Calderone, Cat bonds allow for the cost of disasters to be spread out over several years rather than creating massive immediate demand for funds, and allows the government concerned timely access to liquidity and financing to support the victims. Calderone said this is especially relevant for Indonesia as it has recently experienced a sharp increase in the value of its assets at risk as economic growth and urbanisation gave rise to a highly-populated megacity located in areas exposed to natural hazards.

“However, insurance penetration is still low, insurance markets remain underdeveloped and related technical capacities and regulations are often lacking. It will be crucial to improve local capacities in data collection and analysis to better assess disaster risk exposure and possible financing solutions,” said Calderone.

Public-private partnership

President Director of local Indonesian insurance group PT Asuransi Himalaya Pelindung and Chairman of the Indonesian Earthquake Reinsurance Pool, Kornelius Simanjuntak, as quoted by Cat bonds, reinsurance and insurance linked securities (ILS) platform Artemis, called for a public-private partnership approach to disaster insurance and risk transfer.

According to Simanjuntak, Indonesia could narrow its disaster insurance protection gap by following the Mexican model, where a consortium of insurance companies pool the associated risks, with the government supporting the insurance premiums of the poorest, and reinsurance capacity provided by global reinsurers and the capital markets through catastrophe bond issues, with the assistance of agencies such as the World Bank.

Whatever the basket of mechanism is, it is unreasonable for a disaster-prone country to assume that the state will always be able to absorb the costs of disasters. As Indonesia considers its barriers to better its disaster financing including its regulatory issues, the rest of the countries in the disaster-prone region should sit up and pay attention.

Related articles:

Insuring farmers for food security