Sand mining for reclamation of coastal areas is both, a geopolitical and conservation issue for the Southeast Asian region, with many of the more developed countries in the bloc playing culprits. Leading the regional pack for reclaiming land from its coasts is Singapore, with Malaysia close behind. In Singapore, the total land area has literally grown more than 25 percent since the nation first came into being. The island city-state has so far increased its total land area from 578 square kilometres (km²) in 1819 to 719 km² today.

The continuous supply of sand drives Singapore’s growth both, in land area and economy. Where there used to be only water now stands ports and airports, commercial and industrial areas, as well as luxury hotels, casinos and high-rise apartments. Propping up land growth in the world’s largest sand importer is sand sourced from neighbouring countries, including Cambodia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia, both legally and illegally.

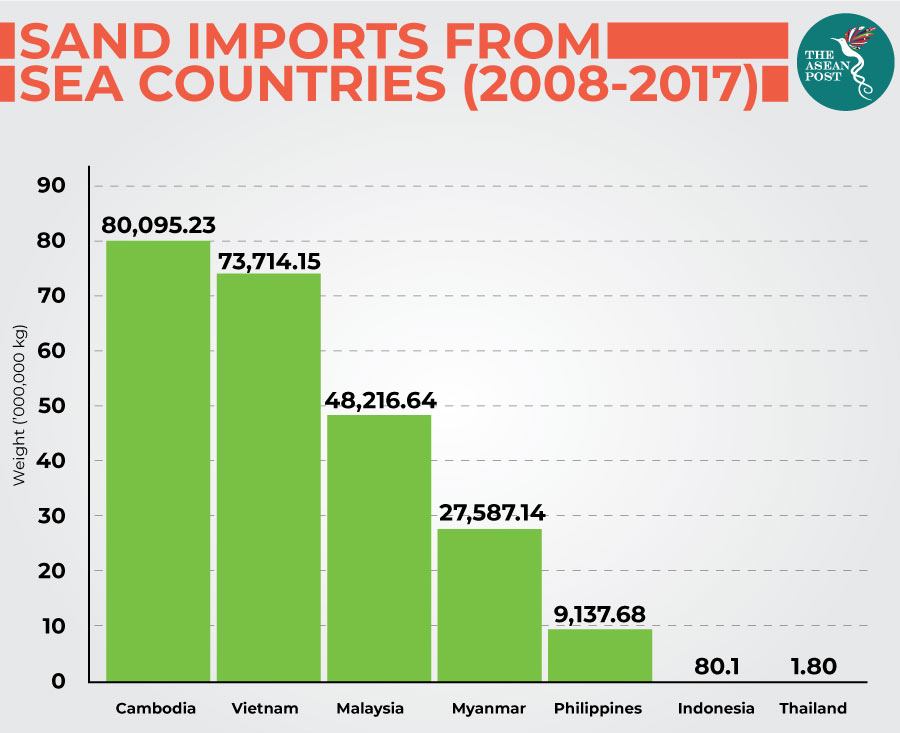

According to the United Nations (UN) data on commodities trade (COMTRADE), in the decade between 2008 and 2017, Singapore imported the bulk of sand used to expand its land area from Cambodia. In the region, Cambodia exports the most sand followed closely by Vietnam, Malaysia, Myanmar and the Philippines, despite various bans announced by the governments of these countries.

While Indonesia contributed only 0.03 percent of the total amount of sand imported from Southeast Asian countries within the past decade, concerns have been raised about the selling of sand in the black market by organised crime syndicates. The Guardian recently reported that illegal sand extraction that ultimately ended up as fodder for Singapore’s growing land area threatens the very existence of some 80 small low-lying Indonesian islands bordering the city-state.

Sand mining resulting in disappearing islands in Indonesia has been going on for decades. In 2003, sand dredging near the Singapore-Indonesia border caused the Nipah island to disappear under the surface completely, leaving only a few palms trees visible to mark its location, according to local NGO Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia.

Plundered resources

Sand dredging and mining seriously impacts on local biodiversity and food security, according to research by Melissa Marschke and Laura Schoenberger at the University of Ottawa that highlights the costs of coastal sand dredging on poorer origin countries. According to Marschke, noise and sediment disturbances damage breeding grounds, scare away marine life, cause mangrove erosion and weaken the natural defence from weather for coastal communities.

“Sand mining is contributing to the erosion of estuaries, the collapse of riverbanks and loss of mangroves. The removal of vast quantities of sand will definitely impact upon coastal erosion. We need to realise that sand is a finite resource and we are overusing it and if we don’t start to manage it properly it has huge implications,” said Marschke.

The evidence of this is presented by the Southeast Asia Globe in a narrative of livelihood lost in Cambodia’s Koh Kong province. Once a thriving ecologically rich fishing ground, the community has been struggling with small fish and crab catches, while some fishing nets have been damaged by dredging machines. This has led to rising indebtedness to middlemen, increasing loans and family members having to migrate for income. Those who protested have also been arrested or threatened with arrest.

Murky areas

This sandy business brought in around US$752 million from Singapore to Cambodia between 2007 and 2016 based on the UN-COMTRADE data as reported by Singapore. However, the Cambodian government claims that the total export worth for the same period was just US$5 million.

“The volume of sand that has been leaving Cambodia over the last 10 years is absolutely illegal; way beyond the government’s permitted limits. Small amounts of sand can be legally exported, but Singaporean import figures reveal that this Cambodian resource is clearly, and rapidly, disappearing. It appears that someone with high level connections in the Cambodian government is making a lot of money” said Schoenberger.

Singapore’s economy rests upon maintaining a huge and continuous supply of sand, whether secured legally, or illegally through smuggling or deals with corrupt officials of origin countries. Singapore’s redrawing of its coastline is making billions of dollars for the crazy rich ASEAN country. But for the land from which the sand comes from, concerns of hunger and poverty beset its people.

Related articles:

The Mekong river continues to suffer