Despite the best efforts of law enforcement agencies and border management officials, organised crime is as rampant as ever in Southeast Asia.

Apart from the thriving drug trade – the methamphetamine market alone is now estimated to be worth up to US$61 billion annually – human trafficking, migrant smuggling and the illegal wildlife trade are among the other pressing challenges which continue to plague the region according to a United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) report released yesterday.

Timber trafficking, the production of counterfeit goods and falsified medicines were identified as criminal syndicates’ other high profit endeavours in the report titled ‘Transnational Organized Crime in Southeast Asia: Evolution, Growth and Impact’. The 179-page report is the most comprehensive study of organised crime in Southeast Asia by the United Nations (UN) in over five years.

Corrupt officials, weak governance and poor border controls help facilitate organised crime in Southeast Asia, and initiatives to boost connectivity have allowed transnational organised crime groups to expand their illicit enterprises alongside growing legitimate commercial flows.

“Like any business, transnational criminal enterprises seek out conditions that are good for the bottom line, and in Southeast Asia conditions have been favourable,” noted Jeremy Douglas, UNODC Regional Representative.

“The fact is that while law enforcement and border management in the region are robust in some jurisdictions, they are effectively not functioning in others, and limited cross-border cooperation and corruption are serious problems – key enabling factors for transnational organised crime are unfortunately in-place,” he added.

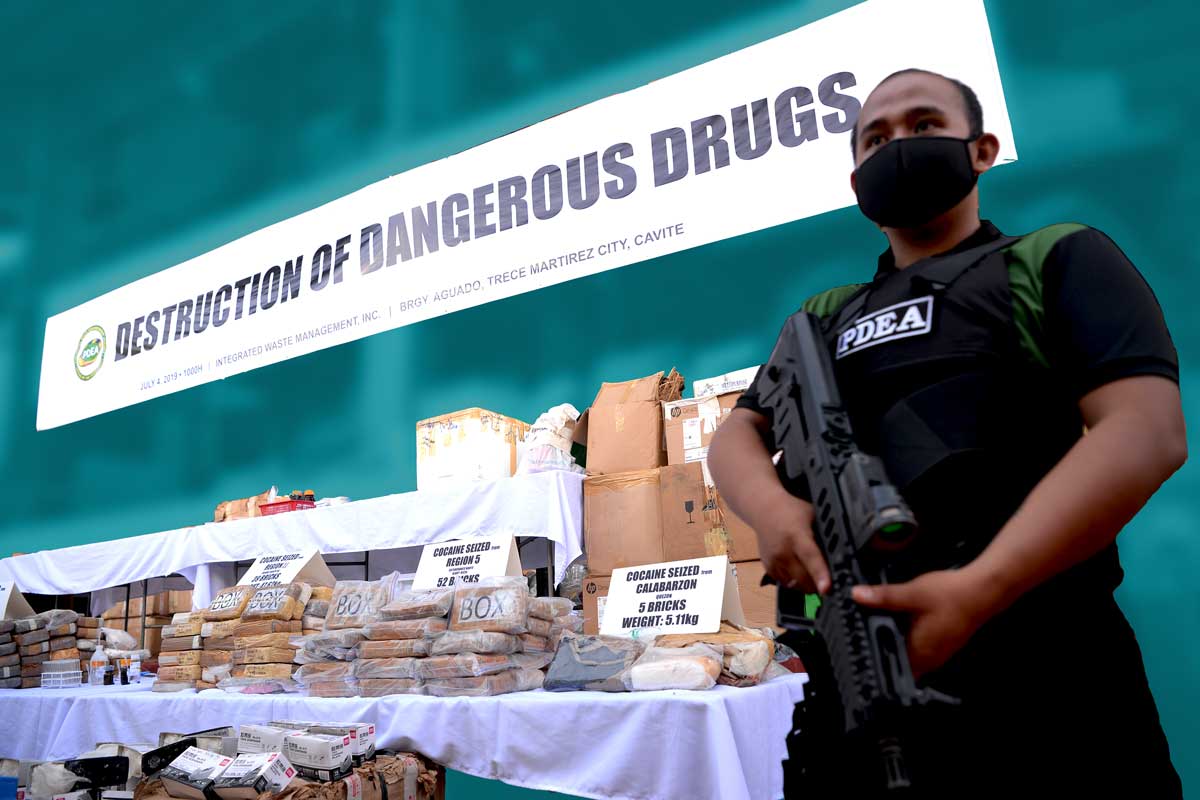

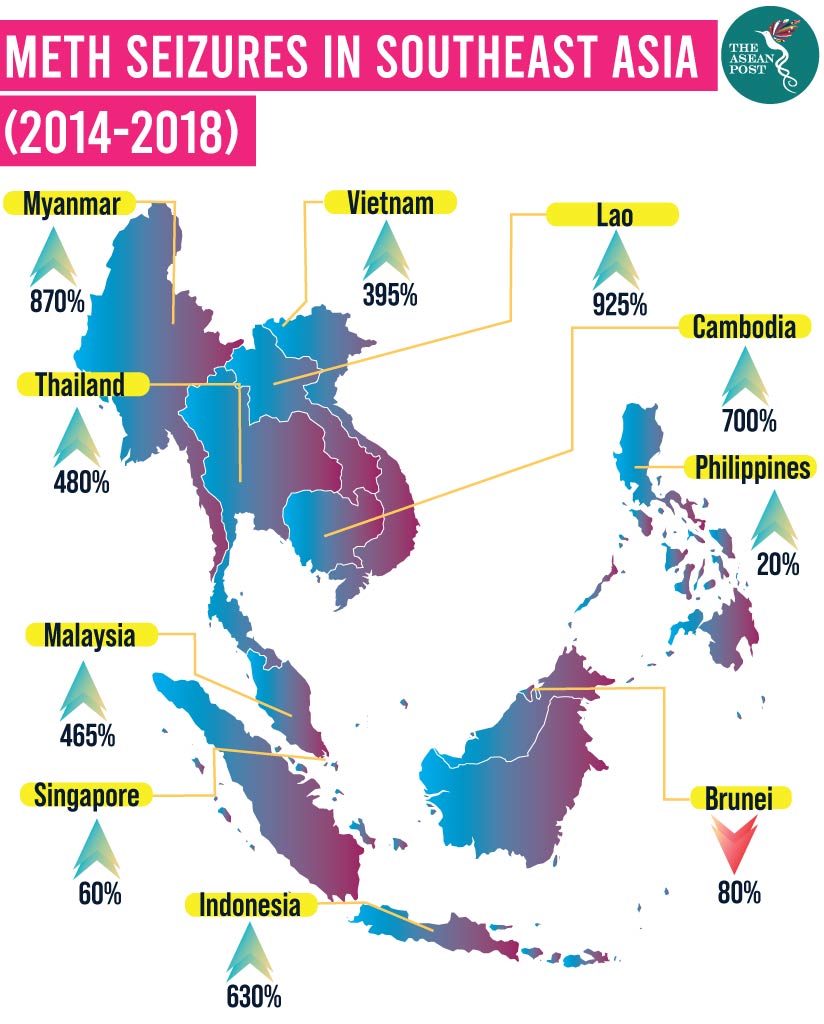

While the UNODC noted that methamphetamine production and trafficking have reached “unprecedented and dangerous levels” in the past few years, the massive profits – estimated to be between US$30.3 billion and US$61.4 billion last year, up from US$15 billion in 2013 – should come as no surprise.

The methamphetamine trade was recently estimated to be worth over US$40 billion a year in the Mekong sub-region alone – an area comprising Cambodia, south-west China, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam. The region’s most-profitable illicit business, one-third of the methamphetamine trade is attributed to more affluent markets such as Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea.

Organised crime’s many faces

Spurred by uneven economic development and demand for cheap low-skill labour, Southeast Asia has become a global hub for human trafficking both as a source and destination region.

As the report observes, the majority of flows within Southeast Asia involve victims being trafficked from less developed countries in Southeast Asia such as Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Vietnam to more developed countries including Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore – as well as to destinations outside the region, particularly China, Japan, South Korea, Europe, North America, the Middle East and Australia.

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation accounted for roughly 79 percent of the total number of cases in Thailand from 2014 to 2017, and of the total number of victims trafficked for sexual exploitation, almost 70 percent were underage girls.

Already plagued by a record number of seizures, Southeast Asia’s illegal wildlife trafficking may increase in value due to declining wild populations, growing demand, stricter national legislation and enforcement and the rise of online commerce and social media as platforms for trade.

As some of ASEAN’s increasing industrial capacity is re-routed to producing unauthorised overruns and cheaper imitations of brand-name products, the UNODC expects the region to remain a major hub in the supply chains for the global counterfeit goods market – which it estimates to be valued at between US$33.8 billion to US$35.9 billion annually.

A common theme underlying all these crimes is money laundering, and the region’s rapidly expanding network of casinos – many of which are lightly or not at all regulated – has become the perfect partner for organised crime groups that need to launder illicit money. As of January, there were 230 licensed casinos in Southeast Asia – many of which emerged after a crackdown on money laundering activities in Macau in 2014.

Attempts to address transnational organised crime have clearly been unsuccessful, and the UNODC has called for the establishment of an overall policy to review and develop connected strategies at individual national levels to ensure more effective mechanisms for cooperation.

With the ASEAN Senior Officials Meeting on Transnational Crime kicking off in Nay Pyi Taw on Monday, regional observers will be looking to the Myanmar capital to see what comes of discussions between the UNODC, governments and international partners on the findings and responses of the damning report.

But while regional connectivity and poor governance has no doubt made it easier for organised crime networks to supply their clients with pills, pangolins and purses, like any other business, they would be bankrupt if not for the continued demand for their products and services.

Related articles: