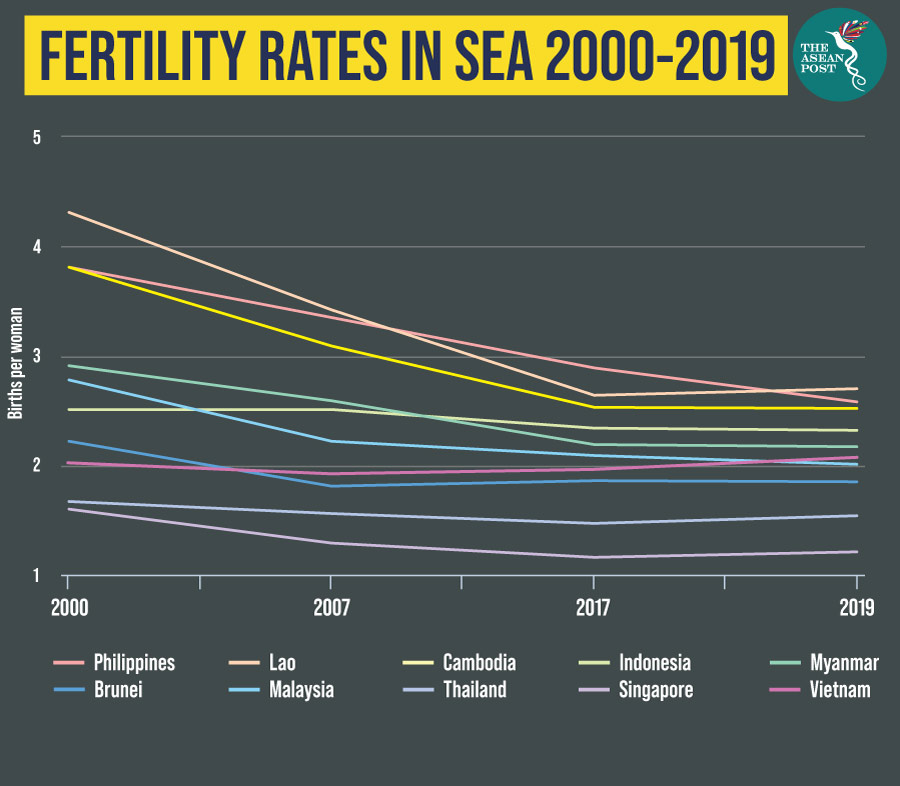

ASEAN countries have collectively achieved remarkable economic growth, however, when it comes to fertility rates, the region has been drifting. The total fertility rate (TFR) of Southeast Asia has dropped from 5.5 in 1970 down to 2.11 in 2017. Half of the region is already facing a ‘baby bust’, where there are insufficient children to maintain the population size. And it is feared that the ongoing decline will have grim economic consequences.

At the Future of Work Conference in Singapore in April 2019, Singapore’s Minister for Manpower, Josephine Teo stated that more than half of the world’s population live in countries with a TFR that is below the replacement level of 2.1. Based on World Bank data, Brunei, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam are ASEAN countries which have a TFR below the replacement level.

While some countries in the region have a rapidly growing youth population in the short term, the size of their working-age population will decline over time. In 2015, the total population of ASEAN aged 65 and above was 7.7 percent. This figure is set to double to 15.5 percent by 2035. An ageing population will increase the pressure on support systems for the elderly.

Singapore has the lowest TFR in ASEAN with 1.21 births per woman, and although several efforts have been taken by the government to increase the fertility rate, the country still saw a decrease in the number of births in 2017 by four percent.

Declining factors

A 2019 report by The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), titled ‘The disappearing workforce’ highlighted the need for ASEAN countries to think about fertility rates before it’s too late. As ASEAN member states transition to aged societies, a large portion of their spending will go to healthcare and infrastructure costs for the elderly, while the working-age population that drives the region’s economic growth decreases.

The EIU found that the factors driving the fall in fertility levels include rapid urbanisation and migration from rural areas to the city, which contributes to the higher costs of raising children and the lack of affordable housing for family building. Another factor is the shift of focus from ‘quantity’ to ‘quality’, where a greater emphasis is placed on raising fewer children with a better quality of life as opposed to having as many children as possible. Dr Le Hoang, Head of Tam Anh IVF Center in Vietnam said that “raising children with a good quality of life has become a challenge for parents; far from the usual concerns about providing basic needs and resources for their children.”

This observation was concurred by Professor Zainul Rashid Mohd. Razi from the National University of Malaysia’s (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia) Specialist Centre who said that “most people emphasize on quality and not quantity to ensure that their child grows up in a stable environment with a good education.”

Declining fertility rates may also be due to a cultural shift where women are increasingly gaining access to higher education and pursuing economic opportunities and consequently delaying marriage and motherhood.

Pervasive gender inequality also exerts a dampening effect on efforts to raise the birth rate. Workplace demands of long-hours at work and extensive workloads will create problems for dual-earner couples unless they have the benefit of co-living with a parent or in-laws to care for their children. Lacking such support discourages women in full-time jobs to have more children. Having men to help in child-rearing and sharing the housework can reduce gender inequality which can then increase fertility rates in the region.

Family-friendly policies

There is a need for the region to address the issue of a low TFR and foster a supportive environment for childbirth and child-raising. The EIU recommends four principles around which governments can build effective policies. The first is to extend family-friendly policies that give greater flexibility for parents to both, work and raise a family. The second is to invest in raising population awareness on family planning and fertility preservation.

The third is to improve access to infertility treatments, such as assisted reproductive technology (ART). Infertility may not be perceived as a sufficiently urgent problem, but making ART affordable by providing subsidies has often found to increase the number of births. And the fourth recommendation is the need to ensure affordable housing to encourage family building.

Efforts could also be made to decrease the cost of child-rearing without disincentivising work for women, such as a provision for workplace childcare. On the financial side, tax relief, cash incentives and subsidies are undoubtedly welcome by most parents.

ASEAN states are in the process of becoming ageing societies. A demographic makeup of ageing generations who are less productive will place a burden on the healthcare systems of all these countries while a shrinking workforce can also result in institutional, economic and social issues.

Governments need to act fast and prioritise how they can make the country as family-friendly as possible. Parenthood should be supported and celebrated, and families need to know their governments are on their side.

Related articles: