A youth group from Cambodia alongside Good Neighbours Cambodia (GNC), recently revealed the results of a survey they conducted on children’s exposure to drugs in communities. Volunteers from the group interviewed 283 children aged from 13 to 18 in Phnom Penh and the provinces of Banteay Meanchey, Battambang, Kratie and Mondulkiri.

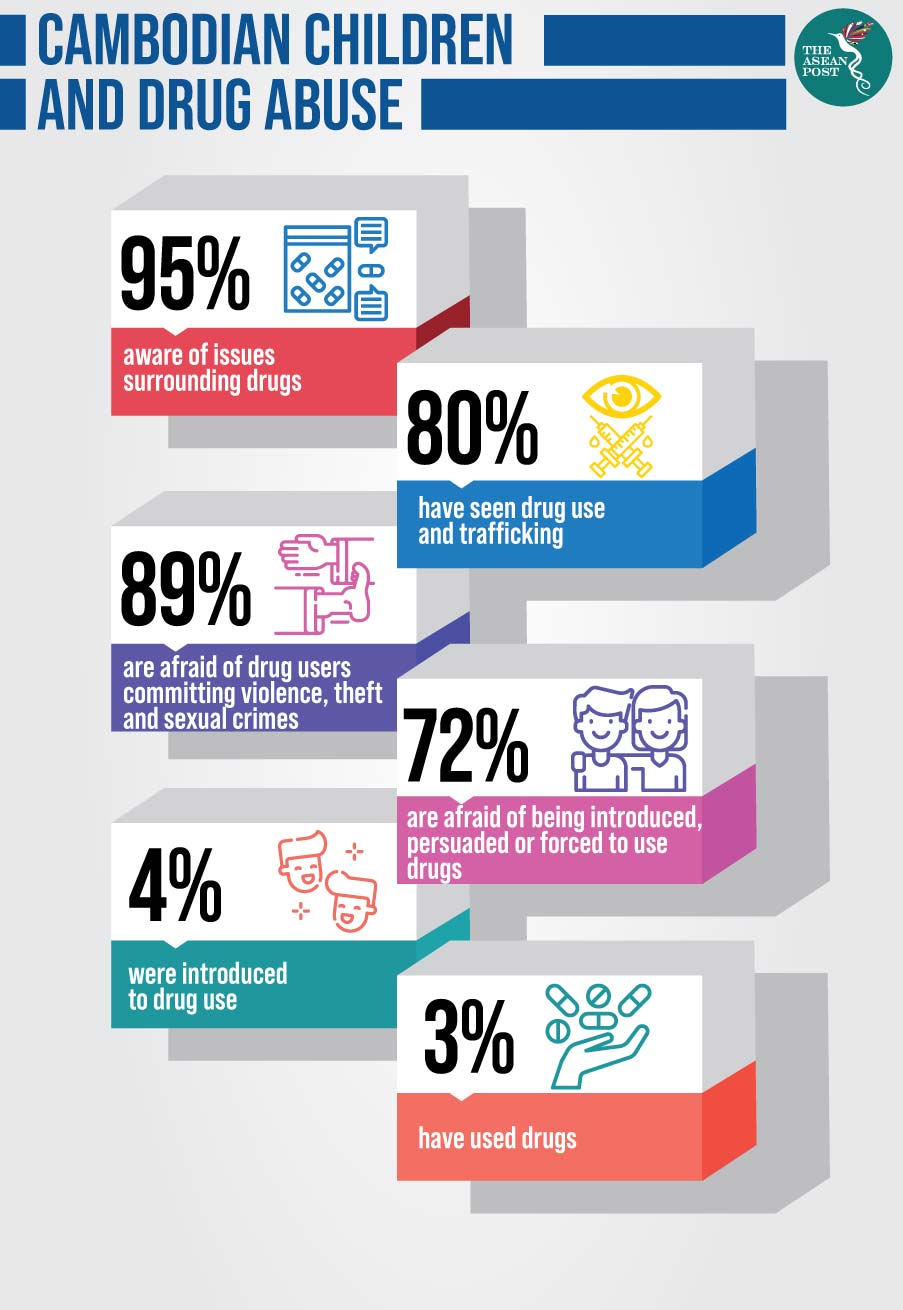

The results of the survey found that 92 percent of respondents said they are aware of issues surrounding drugs, and 80 percent said they have seen drug use and trafficking in the communities they live in. Meanwhile, the survey also found that 72 percent of the children said they are afraid of being introduced, persuaded or forced to use drugs by offenders.

“Drugs are a major obstacle to the development of communities, children and youths. Intervention from the government, police and teachers is most necessary,” Rin Norngkea, head of the volunteer youth group was quoted as saying. She was speaking at a forum organised by GNC and which was attended by representatives of ministries and more than 200 people.

The survey also found that four percent of children said they were introduced to drug use, while three percent said they have used drugs. However, there remains the possibility that some of the children were not willing to disclose whether or not they were introduced to, or have used drugs. This may especially be the case following Cambodia’s war on drugs.

In 2017, Cambodia began cracking down on drugs with renewed vigour. Inspired by the controversial war on drugs waged by Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, who met Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen in December 2016. The Cambodian government said that the crackdown was necessary to eliminate drug trafficking and to track down drug producers.

The crackdown was effective. In 2017, Cambodian police managed to make more than 17,700 drug-related arrests. This number was an increase of a whopping 80 percent compared to the previous year before Cambodia’s war on drugs.

Crackdown spreads fear

Despite the positive results, health organisations and community workers have raised concerns. They claim that drug users have been forced into hiding due to the war on drugs and that it has become more difficult to offer them the treatment they require in order to get rid of their addiction.

In January 2018, a report quoted one such group that works with children complaining about the same issue.

Friends International, a non-governmental organization (NGO) that helps street children and youths, was quoted as saying that the crackdown had made it more difficult to reach drug users, adding that many had taken to hiding from the police by moving from place to place.

As a result, Friends International said it could only help about five percent of drug users twice a week in 2017, down from 40 percent in 2016.

"This means they lack drug health education and have less access to clean needles and syringes," spokesman James Sutherland was quoted as saying.

Friends International provided support to 3,262 drug users in 2017. It offers education and vocational training and refers drug users to methadone maintenance therapy or to hospitals. It also provides clean needles and syringes to prevent diseases such as HIV from spreading.

Thong Sokunthea, deputy secretary-general of the National Authority for Combatting Drugs, however seems to disagree with Friends International, in so far as the lack of drug health education goes. During a recent forum, she said that the government there has been working hard to suppress drug use and prevent trafficking by disseminating information and educating people living in rural communities.

Cambodia has been putting forth many efforts to take care of its children especially. This was also noted in Save the Children’s recent report. While it is important for the government to continue combatting drug trafficking and the spread of drug abuse, it would certainly be worthwhile for Cambodia to also pay attention to some of the complaints put forth by groups against how the government has been approaching its war on drugs.

If the war on drugs has led to drug abusers and drug traffickers hiding in the shadows then this may be a risk to children who are still exposed to influences. A more careful study on how to approach the problem would certainly be welcomed and considering how Cambodia’s government has prioritised the welfare of its children in recent years, there is little reason to doubt that this is what the government will end up doing. We wish Cambodians and their government the best of luck in this important endeavour.

Related articles: