Earlier this year, a Kosovo-born football player, Liridon Krasniqi who plays for Malaysian football club Johor Darul Ta'zim (JDT) was naturalised and given a Malaysian citizenship. Many observers criticised the decision for granting a fast-tracked citizenship to the popular sportsman as thousands of other stateless people in Malaysia are still undocumented. According to media reports, referring to Article 19 of the Federal Constitution – a person must reside in Malaysia for an aggregate of not less than 10 years in the 12 years immediately preceding the date of the application for a naturalisation certificate. However, as of 2020, Liridon Krasniqi has only been in Malaysia for five years since he first entered the country in 2015.

According to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 (CRC), every child shall be registered immediately after birth and shall have the right from birth to a name and the right to acquire a nationality. Unfortunately, according to a report by the Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa – a child born in Malaysia does not automatically obtain Malaysian citizenship, which has led to many stateless children who are sometimes referred to as ‘undocumented children’ in the country.

In 2016, the former home minister of Malaysia, Ahmad Zahid Hamidi estimated that there are around 290,000 stateless children in the country. However, it is unclear of the exact number of stateless individuals given the nature of the problem. Contrary to popular belief, many people who are stateless in Malaysia are not foreigners, refugees or “illegal migrants”; many of them were actually born in the country and have been living in Malaysia most of their lives, according to local media reports.

According to a paper titled, ‘Protecting the Children’s Right to Nationality in Malaysia: An Appraisal’, published by the Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (HRMARS), there are several factors leading to the creation of stateless children in Malaysia – failure of marriage registration by their parents, unregistered births, adopted or abandoned children, and children of refugees and undocumented migrants.

In 2019, an 11-year-old stateless girl, Siti Masitah Ibrahim went missing and her disappearance was then reported to the police. According to local media reports, the reason for her statelessness was because her mother is a Cambodian national and has no identification documents or permanent residency card. In Malaysia, when children under 12 years of age are reported missing, the NUR Alert (National Urgent Response) is activated. The NUR Alert was introduced so that every child under the age of 12 receives protection from exploitation, violence and neglect through alerts that are sent out to enforcement, media and broadcasting agencies. Unfortunately, in the case of Siti Masitah Ibrahim, the NUR Alert never went out.

Police chief Superintendent Amran Sidek from Pekan, a town in the state of Pahang, told local media that the system was not activated because the girl’s parents were foreigners, despite the fact that they have lived in the country since the 1980s. Former deputy minister of Malaysia’s Women, Family and Community Development Ministry, Hannah Yeoh later clarified that the NUR Alert System is applicable for all, regardless of their nationality or documentation. Unfortunately, Siti Masitah’s body was discovered not long after nearby her home.

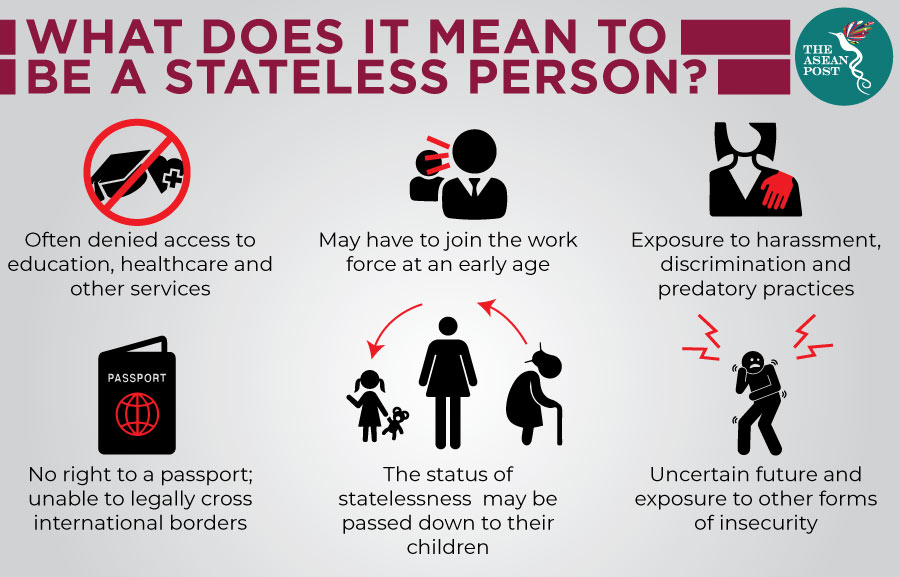

In the same HRMARS paper, it is said that nationality is an important aspect of a child's identity and serves as a 'gateway' to other human rights such as formal education. Unfortunately, stateless children in Malaysia do not have access to a formal education as most public schools do not accept foreigners or undocumented children. Even if they somehow managed to attend school, they are not entitled to education perks such as the Textbook Loan Scheme. A tertiary education in Malaysia would also be as difficult for stateless individuals as they would have to pay foreign student fees which are generally higher and won’t be entitled to a National Higher Education Fund Corporation - or better known locally as PTPTN – loan.

Moreover, stateless children are also denied the right to legal employment, public services and even healthcare in Malaysia. Malaysians are able to use their Identification Card (IC) for unlimited use of public transport for a nominal fee of RM100 (US$23) a month. However, this scheme is not applicable to foreigners or those without an IC. Apart from that, the cost of healthcare in Malaysia is higher for non-citizens which means that foreigners, including stateless and undocumented individuals without an IC would need to pay more for consultations and medication at local clinics and hospitals. This has raised concerns among members of the public regarding the wellbeing of stateless people in Malaysia amid the current COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, health director-general, Noor Hisham Abdullah has recently announced that foreigners will also receive free COVID-19 testing at clinics and public hospitals like other Malaysians do.

“If the foreigners come to a government clinic or hospital for non-COVID-19 diseases, they will be charged the set fee. However, for COVID-19 related illnesses, as per the circular dated 29 January, fees will not be charged, regardless of whether one is poor or rich,” explained Noor Hisham Abdullah.

For many years now, child activists and organisations such as The Family Support Group for Stateless Malaysian Children have been fighting for the rights of children and stateless persons in the country. Many believe that it is unfair for a person born and raised in Malaysia to be treated as a foreigner. The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) says that "stateless children, through no fault of their own, inherit circumstances that limit their potential," and added that "they are born, live and, unless they can resolve their situation, die as almost invisible people."

Related articles: