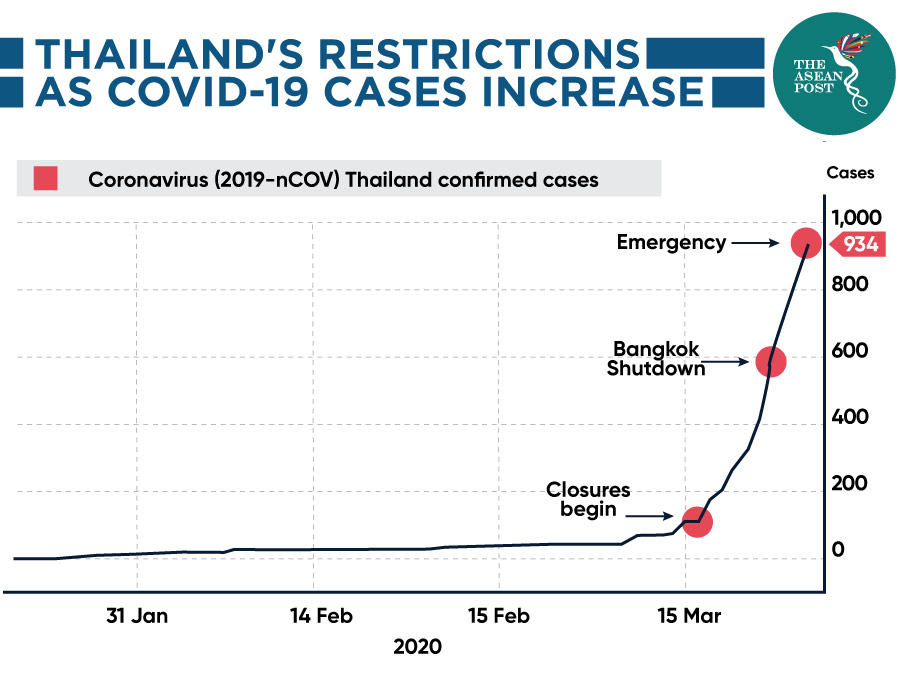

On Thursday, Thailand declared a state of emergency and called for a nationwide lockdown to fight the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to Malaysia's Movement Control Order (MCO), the country's borders are now closed to foreigners while only businesses deemed essential can remain operational.

“Thailand is at a turning point in the outbreak and the situation could get a lot worse,” Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha said in a televised speech. “It’s important that we impose stricter rules to reduce the spread.”

As of 29 March 2020, Thailand reported a total of 1,388 infections, 229 recoveries and a fairly small number of deaths; seven. The Patong beach zone in Phuket, a popular tourist destination, has become a red zone for coronavirus infections as most new cases in recent days were found in the area.

The ASEAN Post recently reported on the effects the global crisis has had on Thailand's multi-billion dollar tourism industry, and subsequent measures the Thai government have implemented to protect it. Now as Thailand is in lockdown without a fixed end date, the level of uncertainty and risks among workers and businesses in different sectors are extremely high.

The Bank of Thailand released a report which estimates a 5.3 percent contraction in this year's economic forecast. Although the Thai government approved another THB400 billion (US$12.2 billion) stimulus package to reduce the impact of the pandemic, the government was criticised for what was seen as a late response. Local media reported that the measures may be too late to ease the impact of the inevitable crash.

This is attributed to Thailand’s heavy reliance on global demand, which had already seen its exports affected by global trade tensions and tourism, even at the early stage of the outbreak.

A scramble to survive

The country has experienced an unprecedented exodus of migrant workers. Just two days before the lockdown, entertainment venues were ordered to close, which caused about 60,000 migrant workers to flee the country – mostly due to the prospect of not being paid or laid off.

"They cannot survive here without income so many decided to leave immediately," said Suthasinee Kaewleklai, coordinator of the Migrant Workers Rights Network.

Most of the migrant workers were from Myanmar, Lao PDR and Cambodia. The unfortunate surge of movement would in turn burden the three respective countries with more imported COVID-19 cases, thus spreading the risk across ASEAN borders.

Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore are the destinations of 91 percent of intra-ASEAN migrant workers – Malaysia and Thailand receive 35 percent each and Singapore 21 percent according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

While the Cambodian Embassy in Thailand urged its migrant workers and students to stay put as COVID-19 fears mount, the immediate needs and prospect of survival for these workers undoubtedly outweighed the risks of spreading the virus further.

Property developers in the country are already in crisis mode, cutting costs where possible and seeking new sources of revenue. Nonetheless, the government made an exemption for construction work – exposing thousands of migrant workers to the disease in the process.

"The reason to keep construction sites open seems to be, if they can continue to work, they should, as they have deadlines," said Sasiwimon Paweenawat, an assistant professor at the School of Economics at the University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce.

Among the different measures taken by the Thai government to assure minimal impact, it seems that a core component to ensuring the financial and health security of workers may have been overlooked – a matter that private companies cannot be expected to handle.

"Very little allowance is being made for migrant construction workers – they are not being given masks or hand sanitisers or any information about the coronavirus," said Brahm Press, Director of MAP Foundation, a migrant rights organisation.

"They should be allowed to return home if they choose to without any penalty, and come back when it is safe. They live in such cramped quarters and have limited access to healthcare; if the disease reaches them, it would be disastrous," he added.

It seems that in both cases – halting or continuing operations – puts migrant workers in a vulnerable position. The lack of policies by the Thai government to appease migrant workers and also to avoid mass movement could have a detrimental effect on the many efforts made by Thailand and surrounding ASEAN countries to prevent the virus from spreading.

Related articles: