Just yesterday, Malaysian media reported that a Rohingya man escaped from a quarantine centre at the Ministry of Health Malaysia’s Training Institute in Tanjung Rambutan, a small town in the west coast state of Perak. Local police are now on the hunt for the migrant. It was reported that the 27-year-old man, Rohim Mohd Zokoria was initially placed at the quarantine centre on Saturday after being detained.

“However, a screening done at the Slim River Hospital found that the suspect was negative for COVID-19, and he was sent back to the quarantine centre to be quarantined for 14 days,” said district police chief ACP A Asmadi Abdul Aziz.

This was not the first incident of a migrant escaping after being screened for COVID-19. In early May, Malaysia’s police arrested 11 out of 145 migrant workers at a construction site in the country’s capital, Kuala Lumpur who fled after undergoing COVID-19 testing. It was reported that police are also tracking nine other male migrant workers – six Indonesians and three Bangladeshis – who also escaped from a COVID-19 quarantine centre in the capital city around the same time.

In recent weeks, authorities in Malaysia have scaled up immigration arrests, including a series of migrant crackdowns on COVID-19 red zones and areas with large migrant and refugee dwellings. Heidy Quah, founder of Refuge For The Refugees (RFTR) – a non-governmental organisation (NGO) advocating for refugee children, said kids as young as four had been picked up in these immigration raids.

This has raised fears of being detained among migrants in the country.

“The fear of arrest and detention may push these vulnerable population groups further into hiding and prevent them from seeking treatment, with negative consequences for their own health and creating further risks to the spreading of COVID-19 to others,” noted the United Nations (UN) in a statement.

Just like ASEAN member state Singapore, Malaysia has recently seen an increase in COVID-19 infections among its migrants. This is due to the ongoing clusters at the country’s Immigration Detention Centres.

"These raids under the pretence of stopping the spread of COVID-19 have only served to further spread the virus," Beatrice Lau, Head of Mission for Doctors Without Borders (Medecins Sans Frontieres, or MSF) in Malaysia told local media. "The authorities had been warned about the risk of infection in detention centres many times."

Observers believe that these overcrowded immigration detention centres could potentially become the country’s “coronavirus hotspot”.

The Malaysian Health Coalition, Malaysian Trades Union Congress and Beyond Borders Malaysia, alongside nine other NGOs, have urged authorities to improve the living conditions for migrant workers and also the conditions in detention centres.

In a joint statement, the organisations said that “immigration detention centres are Crowded and Confined areas where Close conversations are unavoidable – the three Cs that the Health Ministry has advised against. These conditions must be improved to allow for necessary physical distancing measures which will help prevent further COVID-19 outbreaks.”

On 30 May, Malaysian authorities reported that 384 undocumented migrants tested positive for COVID-19 at immigration depots across a few locations on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur after testing 4,807 detainees.

“Out of those sent for treatment, 26 have been discharged and we will arrange for their deportation to their countries of origin,” said Senior Minister Ismail Sabri, referring to the group of undocumented migrants who have recovered from the disease.

The minister said the deportation process will start with Indonesian citizens on 6 June.

“The first phase, which starts on 6 June, will involve 2,189 Indonesians, who are currently being detained at immigration depots in Peninsular Malaysia and Sarawak, as well as 672 at depots in Sabah.”

Phase two will involve 2,623 people who will be sent back within two months. He also added that the Immigration Department and Wisma Putra (metonym for Malaysia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs) are currently in talks with Nepalese and Bangladeshi officials regarding 246 Nepalese and over 2,000 Bangladeshi undocumented migrants, according to local media reports.

What About The Rohingya?

Malaysia has seen a rise in xenophobic sentiments recently against Myanmar’s Rohingya refugees, accusing them of being a burden on state resources. A few anti-Rohingya petitions were posted online, demanding that they be deported from Malaysia.

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), as of February 2020, there are some 178,990 refugees and asylum seekers registered with the agency in Malaysia – the majority are from Myanmar, comprising some 101,010 Rohingya.

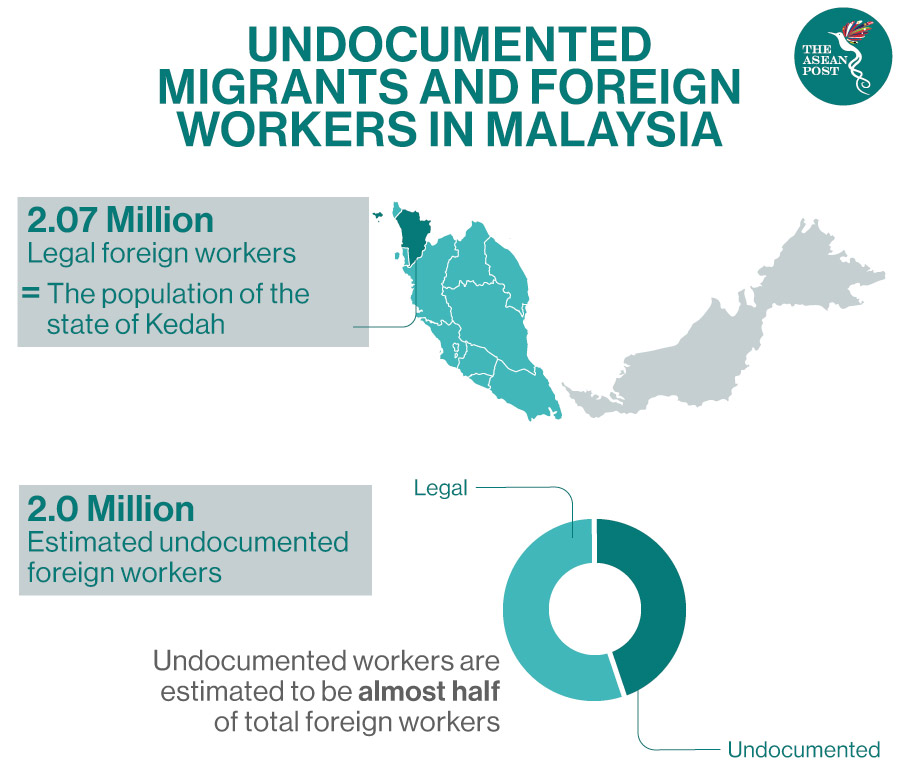

Malaysia is not a signatory to the 1957 Refugee Convention, or its subsequent 1967 Protocol which highlights that refugees should be given the right to earn a living, access to education and freedom of movement. This means that refugees in the country are considered undocumented migrants or commonly referred to as “illegals”.

As Malaysian authorities have initiated plans to send undocumented immigrants back to their respective countries, one can’t help but wonder where would Rohingya refugees be sent to: Cox’s Bazar – the world’s largest refugee settlement? Back to Myanmar where they are allegedly subjected to repeated violence? Or simply cast away to drift in international waters?

Rahman, a Rohingya refugee currently residing in Malaysia told local media that he is genuinely afraid that his community will be deported. He said he wants to go back to his home country but it’s not the safest option right now.

"I have no idea whether I will be able to go back. I just hope I can go back to my hometown with full rights and dignity one day," says Rahman.

Related articles: