Although Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha announced Thailand’s commitment to the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) in 2017, outbound investment remains a largely unregulated sector.

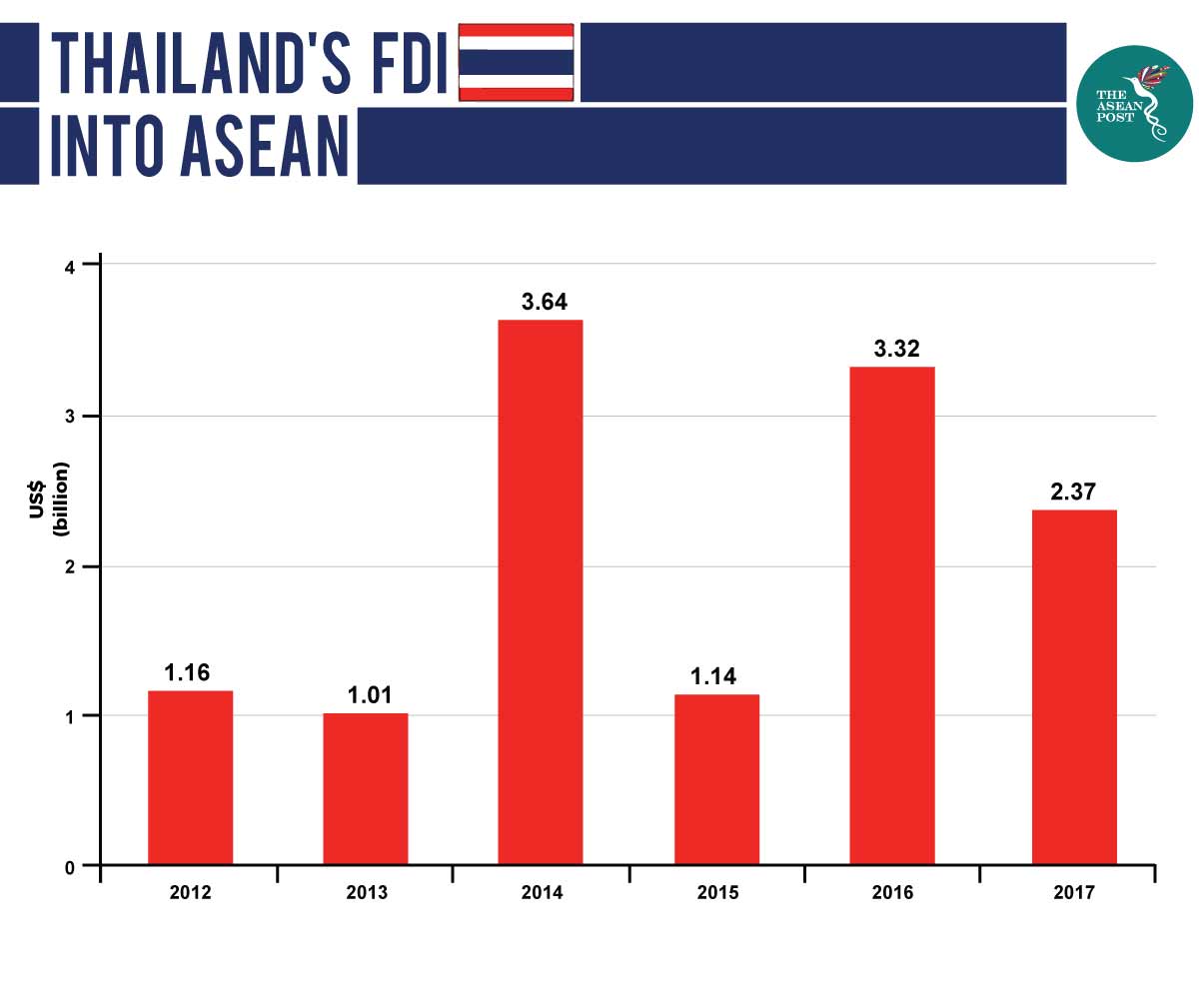

Thai firms are significant investors in ASEAN countries, and Thailand’s foreign direct investment (FDI) in the region stood at US$2.37 billion in 2017 – behind only Singapore (US$18.75 billion) and Malaysia (US$3.99 billion).

Thai companies also have a vast reach. The Siam Cement Group, for example, has more than 90 subsidiaries operating in ASEAN outside Thailand – and more than 55 of them operate in Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam. Another Thai conglomerate, the Charoen Pokphand (CP) Group, has farming, food and telecommunications interests throughout the region.

Short-term profit

However, some Thai firms have taken advantage of weak investment laws in neighbouring countries by developing large-scale projects which have led to environmental degradation or human rights abuses such as land grabs.

While these projects would probably have not got off the ground in Thailand due to opposition from local communities or restrictive national requirements, ASEAN’s failure to provide a regional regulatory framework for social and environmental investment standards has also played a part in these companies’ continued focus on short-term profit over long-term sustainability.

Although environment, social and governance (ESG) is a relatively new concept in ASEAN boardrooms, some 89 percent of the 140 large investors, asset owners and asset managers polled at an investment forum in Thailand last month said that ESG-integrated investment portfolios are likely to perform as well, or better than, non ESG-integrated portfolios.

Energy needs in ASEAN have risen in tandem with its population and economy, and while Thailand has capitalised on this by developing a variety of projects in neighbouring countries, many of them have been criticised for failing to meet ESG standards.

The National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (NHRCT) found that of the 2,119 complaints received concerning adverse business-related human rights impacts from 2001 to 2018, the three most frequent complaints were the adverse effects of environmental pollution on human health, forced evictions of communities with no or inadequate compensation, and lack of or inadequate public consultations with communities affected by large-scale development projects.

Land grabs and coal

The Dawei Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Myanmar, Koh Kong and Oddar Meanchey sugar plantations in Cambodia and the Hongsa Mine and Power Station in Lao are partially owned by Thai investors – and they have all come under fire by local communities and other stakeholders for land grabs.

Non-governmental organisation (NGO) EarthRights International has noted how 456 Cambodian families from three villages were forced out of around 5,000 hectares of land to make way for a sugar plantation in Cambodia’s Koh Kong province, while petrochemical industries have polluted local water supplies in the Dawei SEZ.

Coal projects in the Mon and Kayin states in Myanmar, the Koh Kong province in Cambodia, and both East and South Kalimantan in Indonesia have also been blamed for their impact on the environment. Just last month, the Philippines’ opened a coal-fired power plant in Quezon – a joint venture between the Philippines’ Meralco PowerGen Corporation (MGen) and Thailand’s EGCO Group.

Although coal is a cheap way to power ASEAN’s growing energy needs, it is by no means clean. In Thailand for the recent ASEAN Summit, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres said that Asia has an “addiction” to coal and called for a halt in new coal-fired power plants.

Greater awareness

While Thai firms undoubtedly have a key role to play in ASEAN’s economy, they are slowly realising that increasing the wealth of shareholders can no longer overshadow the long-term goals of social harmony, inclusive growth and sustainable development centred on ESG.

In August, the Bank of Thailand, the Thai Bankers Association and 15 Thai banks agreed on a set of guidelines which takes ESG criteria into account.

For the Government Pension Fund of Thailand (GPF), their ESG-focused portfolio posted a 10-month return of 4.6 percent, outperforming its main equity fund by 50 basis points according to Stock Exchange of Thailand Governor Seree Nonthasoot in a recent interview with a regional trade journal.

During a panel discussion on Lao PDR’s controversial Xayaburi dam on 22 October, Sarinee Achavanuntakul – founder of Sal Forest, a corporate sustainability research firm – said that Thai bankers are now no longer merely repeating borrowers’ promises that proper environmental and social impact assessments were conducted – and heeded – before the start of projects.

Financed by six Thai banks in an investment Sarinee said was a “no-brainer” for the average Thai banker, the newly-operational dam has been blamed for contributing to historically low water levels on the Mekong river.

“During the Sustainable Banking Forum in August, bankers from Kasikornbank and Siam Commercial Bank – two of the dam’s lenders – conceded they may need to look at more standards when financing hydropower projects,” said Sarinee, a former banker herself.

“A senior banker said he was not sure if the drought was related to the dam but said it was a controversy they had to look into.

“You may think that's not saying much, but… It’s a move in the right direction.”

Related articles:

Thai energy companies growing abroad