Last week, Malaysia’s Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng tabled the country’s 2019 Budget. Being the first budget under a new government led by the Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan), there were obviously numerous key points to look out for. One of those key points is the taxing of services imported into the country, which includes online services.

The service tax, according to Lim, will be imposed in phases beginning with services imported by businesses in January, next year. As for online services imported by consumers, the Finance Minister said the government would impose and remit service tax on online services such as software, music, video and digital advertising beginning January, 2020. These online services will also have to register with the Royal Malaysian Customs.

The rationale, according to the government, is to ensure that there is fair competition between overseas and local providers of services. PwC Malaysia seems to agree with this logic but points out that it does not tackle the real issue at hand.

“Although this is a good move in ensuring that imported services are not provided preferential treatment, the Budget still does not tackle the issue which plagues many developing and developed countries, i.e. the taxing of the digital economy itself,” explained Jagdev Singh, Tax Leader at PwC Malaysia.

Although the amount foreign business will be taxed has still not been revealed, if the numbers are anything to go by, the decision to impose a service tax on imported services could rake in significant revenue.

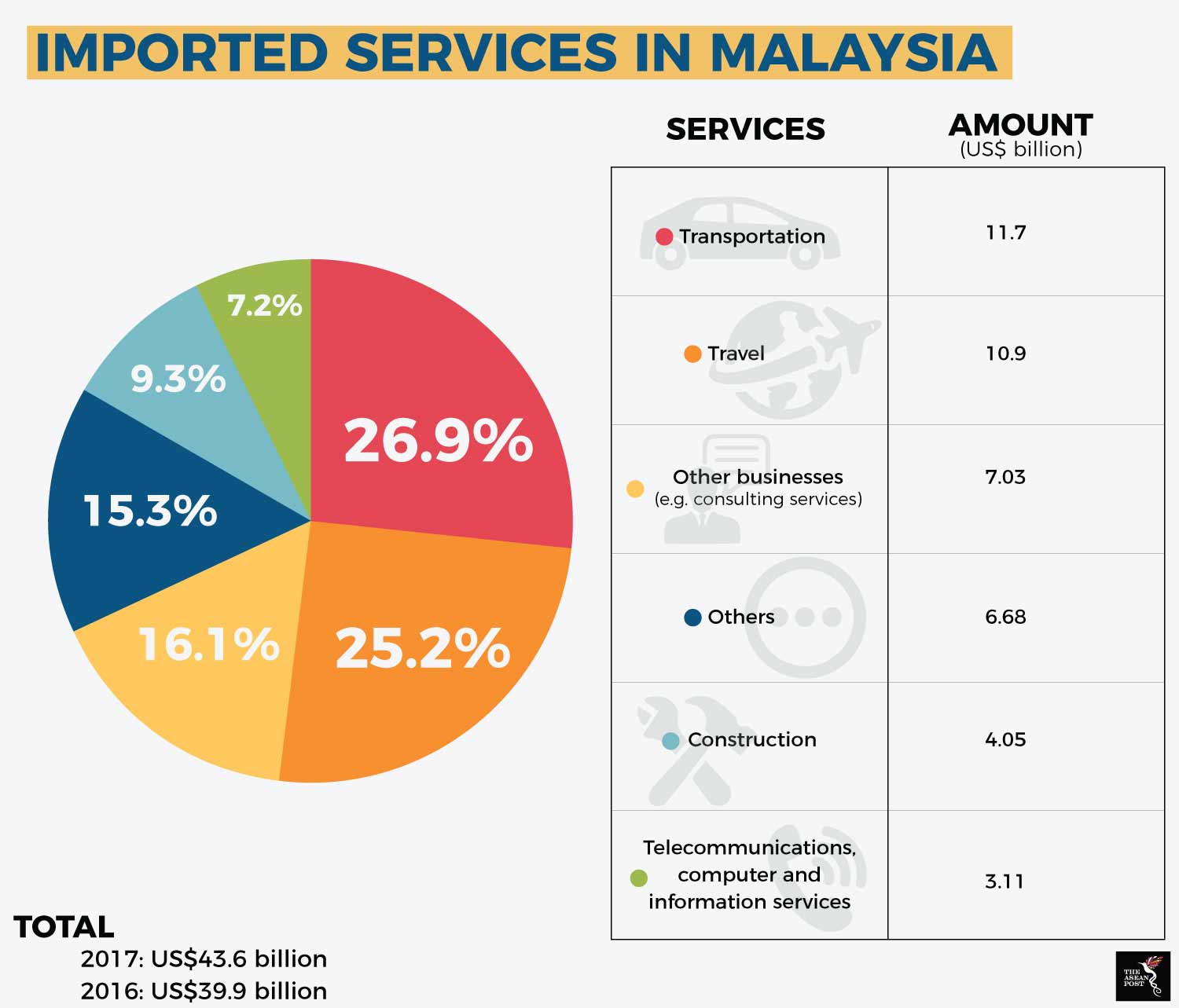

According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia, total services imported amounted to US$43.6 billion in 2017 compared to US$39.9 billion in 2016. Of this, 26.9 percent (US$11.7 billion) came from transportation; 25.2 percent from travel (US$10.9 billion); 16.1 percent (US$7.03 billion) from other business services which includes professional and management consulting services; 9.3 percent (US$4.05 billion) from construction; 7.2 percent (US$3.11 billion) from telecommunications, computer and information services; and 15.3 percent (US$6.68 billion) from others.

Source: Malaysia Department of Statistics

Netflix and iflix

In a 2017 study conducted by Netflix, the popular online video streaming service found that Malaysians topped the list of viewers who binge-watch television series in Asia, ranking ahead of Singapore, the Philippines, Taiwan and Hong Kong.

According to Netflix, binge racing behaviour has contributed to growing its members from 200,000 in 2013 to more than five million in 2017.

But Netflix isn’t the only player in the country. Another significant option for Malaysians is iflix. While Netflix offers international blockbusters and popular TV shows, iflix offers more localised and non-English content that reflects the diversity of the region.

Netflix’s monthly subscriptions are pricier compared to those of iflix. With the incoming services tax, it would not be a surprise if Netflix raised its prices to maintain its profit margins. However, this could result in subscribers turning to iflix for their viewing pleasure.

Other taxes in ASEAN

Foreign companies will undoubtedly want to leverage on the growing ASEAN market and online services tax may be something they’re forced to live with. Malaysia isn’t the only ASEAN market that will be taxing online services.

Indonesia, ASEAN’s most populous member state, has plans to require online merchants to own tax identification numbers beginning this year. The country hopes that this will boost revenue as well as improve compliance in the fast-growing e-commerce industry.

Among Indonesian e-commerce companies which will begin asking sellers for identification numbers are PT Tokopedia and PT Bukalapak.com. This will be the condition they set for sellers who wish to operate on their platforms.

Like it or not, foreign companies will soon have to pay up if they intend to turn a profit from ASEAN markets and that’s only fair. There are risks associated with the move such as the brunt of the cost being borne by people who use these services, but if ASEAN is able to provide viable alternatives then it’s likely that these risks can be limited. The next task will be to strengthen entrepreneurship in the region, a goal that most ASEAN member states are already looking into.

Related articles:

Malaysia’s digital tax: A smart move?

The state of video streaming in Southeast Asia