The digital economy stands to change the way we look at taxes. In Malaysia, the previous National Front-led government was mulling the decision to raise revenue by taxing the digital economy. The newly elected Alliance of Hope government has sought to continue along this same path and look into a possible “digital tax” to be announced at the annual tabling of the country’s budget for 2019 next month.

In September, the newly elected government of Malaysia scrapped the unpopular Goods and Services Tax (GST) and reintroduced a Sales and Services Tax (SST). Expected revenue collection from SST is approximately US$5.1 billion as opposed to the collection of US$10.3 billion from GST from 2016 to 2017. Hence, the government there is looking to bridge this shortfall through various other means including slashing operational expenditure and taxing the digital economy.

According to a brief published by the Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (IDEAS), a Kuala Lumpur based think tank, the arguments for digital taxation are broadly based on two factors. Firstly, digital companies pay lesser tax than non-digital companies and secondly, digitalisation has fundamentally changed the manner in which value is generated.

However, the authors of the brief concluded that there remains “no definitive evidence that digital companies pay less tax than traditional companies.” Nevertheless, at which point in the digital supply chain tax should be paid is still a point of contention as the internationally agreed upon principle of taxing business income is that it should be applied to the area where value is generated. Hence, it is vital to avoid double taxation which can hamper the growth of the digital economy.

Source: IDEAS Malaysia

Source: IDEAS Malaysia

Youths hardest hit

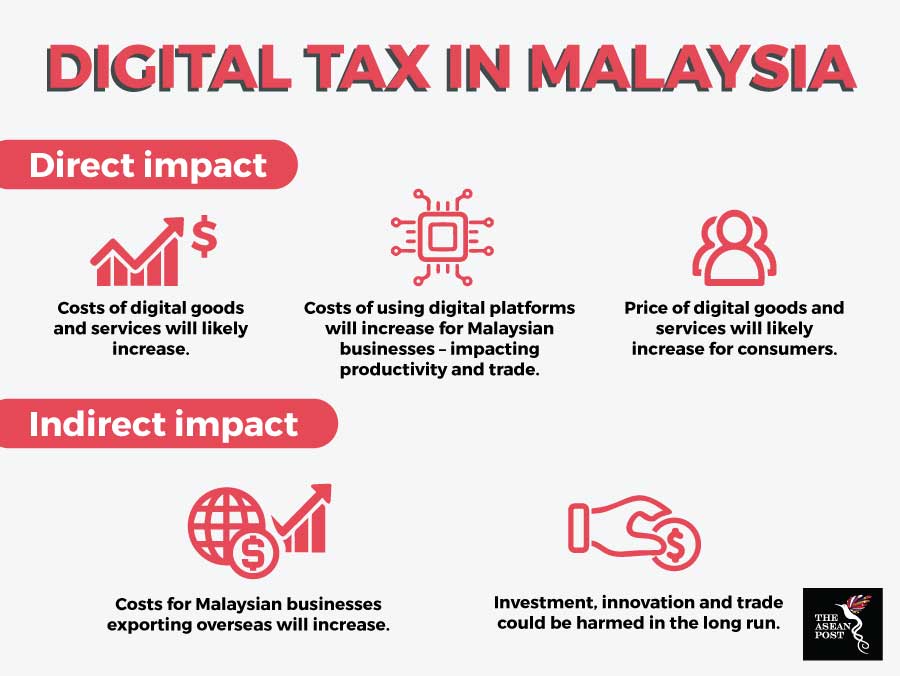

Although revenue can be bolstered in the short term, a digital tax would undoubtedly increase the price of digital goods and services in Malaysia which would in turn pinch the pockets of the Malaysian consumer.

According to the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), youths between the ages of 20 and 39 represent 75 percent of online shoppers in the country.

Adli Amirullah, an economist at IDEAS opined that the most afflicted would be the youth segment of society that have relatively lower or no income at all.

He explained that a digital tax would impact the youth segment from two sides – consumers and entrepreneurs. As consumers, the youth segment would have to pay higher prices for digital services used primarily by them like Spotify and Netflix. On the entrepreneur side, a digital tax could mean higher digital business infrastructure costs like cloud services and the use of e-commerce platforms.

Nevertheless, Amirullah admits that a digital tax remains a necessary evil for the government in order to increase its revenue base.

“No one likes taxes and I am sure a digital tax is not an exception. However, the government needs to be really careful when it comes to digital tax,” he told The ASEAN Post. “If the tax is too high, it may produce huge negative externalities where innovation and productivity may be dampened in the long run.”

As such Amirullah warns that the government must tread a fine line to ensure that they are not creating a huge deadweight loss which may demotivate young entrepreneurs from investing their time and resources in e-commerce.

“E-commerce is a huge industry by itself and we should encourage youth to utilise this platform to export goods and services. Ultimately, these innovative and entrepreneurship activities will provide greater benefit to the country in the long run” he added.

He opined that one way the government could implement the tax is by taxing the consumption of digital goods and services instead of taxing companies directly.

“What the government can do to minimize the negative externalities of a digital tax is to provide incentives to young entrepreneurs that utilise e-commerce as their business model to promote higher entrepreneurship activity among the youth in the country,” he said.

As such, the Malaysian government is now tasked with ensuring proper fiscal discipline without compromising innovations that could hamper the development of its future digital economy.

Related articles:

Who will be affected by Singapore’s digital service tax?

Angpaos, GST and Carbon Tax: A look at Singapore’s Budget 2018

Are e-commerce taxes materialising on the Southeast Asian horizon?