As thousands of national, sectoral, business and community leaders gathered in Katowice, Poland, for the 24th Conference of the Parties (COP24) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the focus heightened again on the issue of decarbonising the energy system. Achieving the Paris Agreement target of “well below 2.0 degree Celsius” warming will mean that renewable energy as a central element of the future energy system, supported by a robust effort to improve energy efficiency, is unavoidable.

With energy demand expected to grow 50 percent by 2025, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has set an ambitious target of securing 23 percent of its primary energy from renewable sources. This target will entail a two-and-a-half-fold increase in the modern renewable energy share compared to 2014, including additional capacity in solar, hydro, wind, and geothermal. The key challenges remain to meet the growing demand without negatively impacting on energy security, the environment and wellbeing of its population.

For many leaders, the decision to pursue renewable-driven energy transformation may prove to be unpopular. The high cost of adopting renewable energy technologies, as well as limited access to financial support, continue to be the main deciding factors. The investment needed to achieve the ASEAN target is substantial, estimated at US$290 billion. Discouraging factors for the uptake includes concerns on the impact of transformation on labour, as well as geographical, technical and regulatory barriers.

How it will play out in Southeast Asia

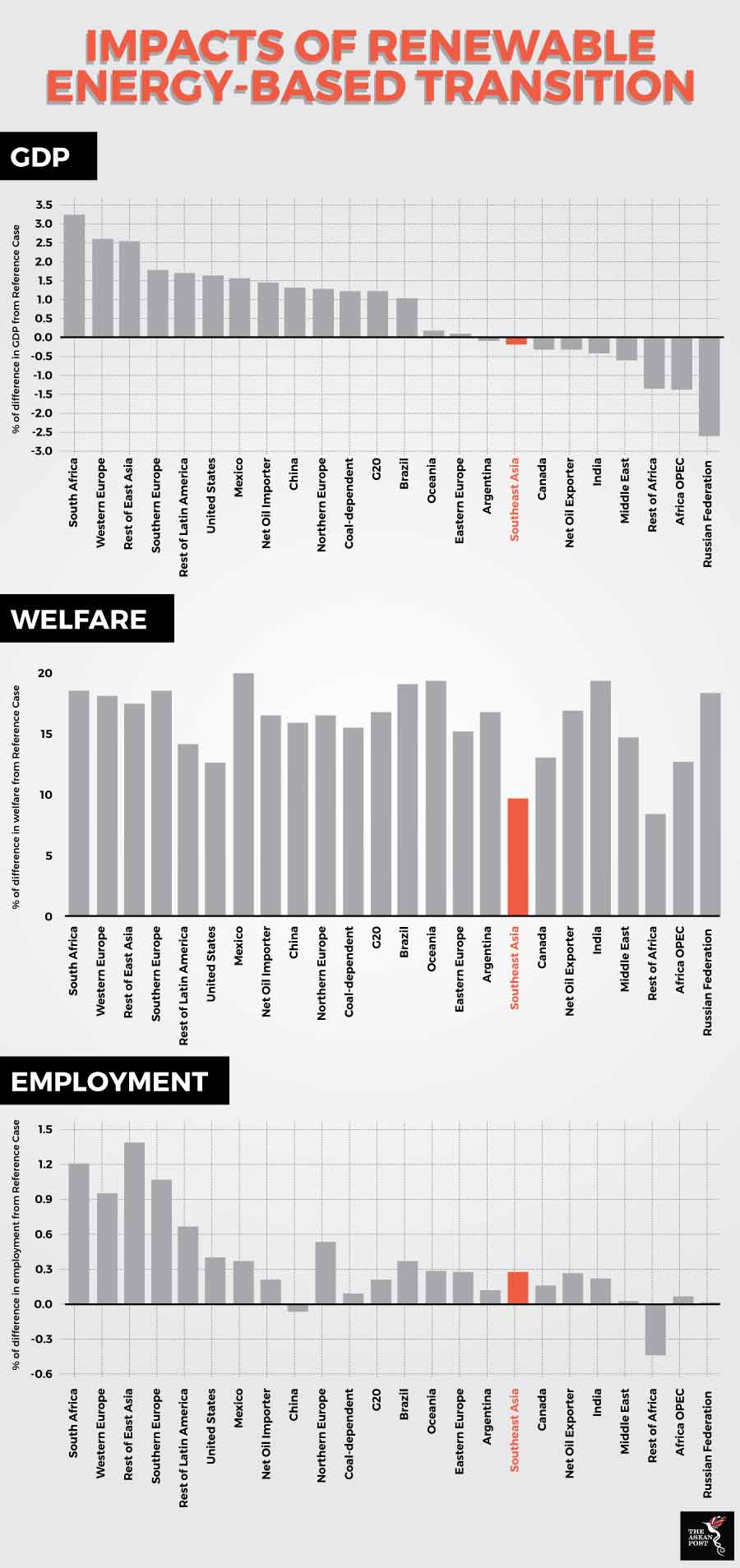

According to the ‘Global Energy Transformation: Roadmap to 2050’ report by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), the transition to renewable energy will significantly improve the global socio-economic footprint of the energy system. The report forecasted that globally by 2050, the decarbonisation of the energy system will generate a 15 percent increase in welfare, one percent increase in gross domestic product (GDP), and 0.1 percent in employment.

Impacts on specific economies may differ based on potentials, national endowment and current economic output. In Southeast Asia, a coal- and petroleum-dependent region, the GDP will be impacted negatively marginally, due to the fall in fossil fuel revenues, which in turn, is expected to increases income tax for consumers.

However, gains in welfare from the energy transition will balance out on marginal loss in GDP in the long run. The energy transition is expected to generates broader socio-economic benefits, including from the impact of expenditure in human capital and education, reduced health impacts from air pollution, reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and depletion of natural resources. Southeast Asia is expected to gain a significant overall improvement of almost 10 percent. While the GDP improvement peaks after about a decade, welfare improvement, including cost saving due to improvement in health and environmental conditions, will continue to 2050 and beyond.

For employment, the energy transition will also generate positive impact in almost all regions and countries, although it will fluctuate over time. Southeast Asian countries, along with South Africa will benefit the most from increased investment in the long term. However, Southeast Asia could face the most adverse impacts on trade by 2050, due to the negative impact of changes in non-energy trade.

Source: IRENA.

Powerful social argument to fuel transition

Focussing on the socio-economic benefits of energy transformation may provide a powerful social argument and political tool, according to Elizabeth Press, Director of Planning and Programme Support, at IRENA. While coupling the issue of decarbonisation of the energy system with climate change may be contentious for some, highlighting the socio-economic gains from the exercise may garner more support.

“Energy and economy are not contained within itself, they are embedded into a holistic system. It is not easy to make changes. It requires longer term planning. Some politicians may not be eager to make unpopular decisions and some decisions will be unpopular. But with thought and planning, socio-economic gains can be a powerful social argument and political tool.

“The most significant impact is in global welfare, health being a major aspect, but environment as well. We estimate that the benefit would be five times the cost of additional investment for renewable energy-based transition. Energy transformation based on renewable energy and efficiency is not just a tool for climate change and decarbonisation, but also for economic development, social inclusion and common progress,” she said at COP24.

Climate change is in the here and now. We are currently living in a one-degree Celsius temperature increase world, with the likelihood of hitting a 1.5-degrees increase by 2030. For many, especially the world’s most vulnerable, the world is a tough place to live in even at the current level of warming. Decarbonisation of the energy system needs to take place or more of us will not be able to cope with the changes.

Related articles:

Indonesia’s wind energy potential

Overcoming barriers in renewable energy financing for Southeast Asia

Small hydropower in Southeast Asia

Designing bankable PPAs for renewable energy projects in Southeast Asia