Following the landmark electoral victory of the new Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan) government in the 14th Malaysian general election on 9 May, 2018, the new cabinet has wasted no time in making changes. One of the changes includes the return of the Department of Marine Park Malaysia (DMPM) from the then Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MNRE) to the Ministry of Agriculture (MOA).

The proponents of the move welcomed the transfer of the DMPM, now absorbed under the Department of Fisheries Malaysia (DOFM), as it used to be under the MOA. However, many experts in the field of marine conservation are deeming the move a conflict of interest. The key issue is not whether there are sufficient marine-related experts in MOA; as clearly there are many.

However, there are major differences between experts in marine resource extraction and marine resource conservation. One group aims to keep propagating it to be harvested for consumption, the other aims to keep propagating and sustaining it in the marine environment for posterity. This was highlighted by Reefcheck Malaysia General Manager, Julian Hyde, who stressed the contradiction between DMPM and its new locus.

“The Ministry's goal is to maximise resource extraction. It seems to me that the Agriculture and Agro-based Industry Ministry's mindset is at odds with a resource conservation mindset. There is a conflict there...the resource extraction mindset will overcome the resource conservation mindset,” Hyde was quoted in the local media there.

The backstory

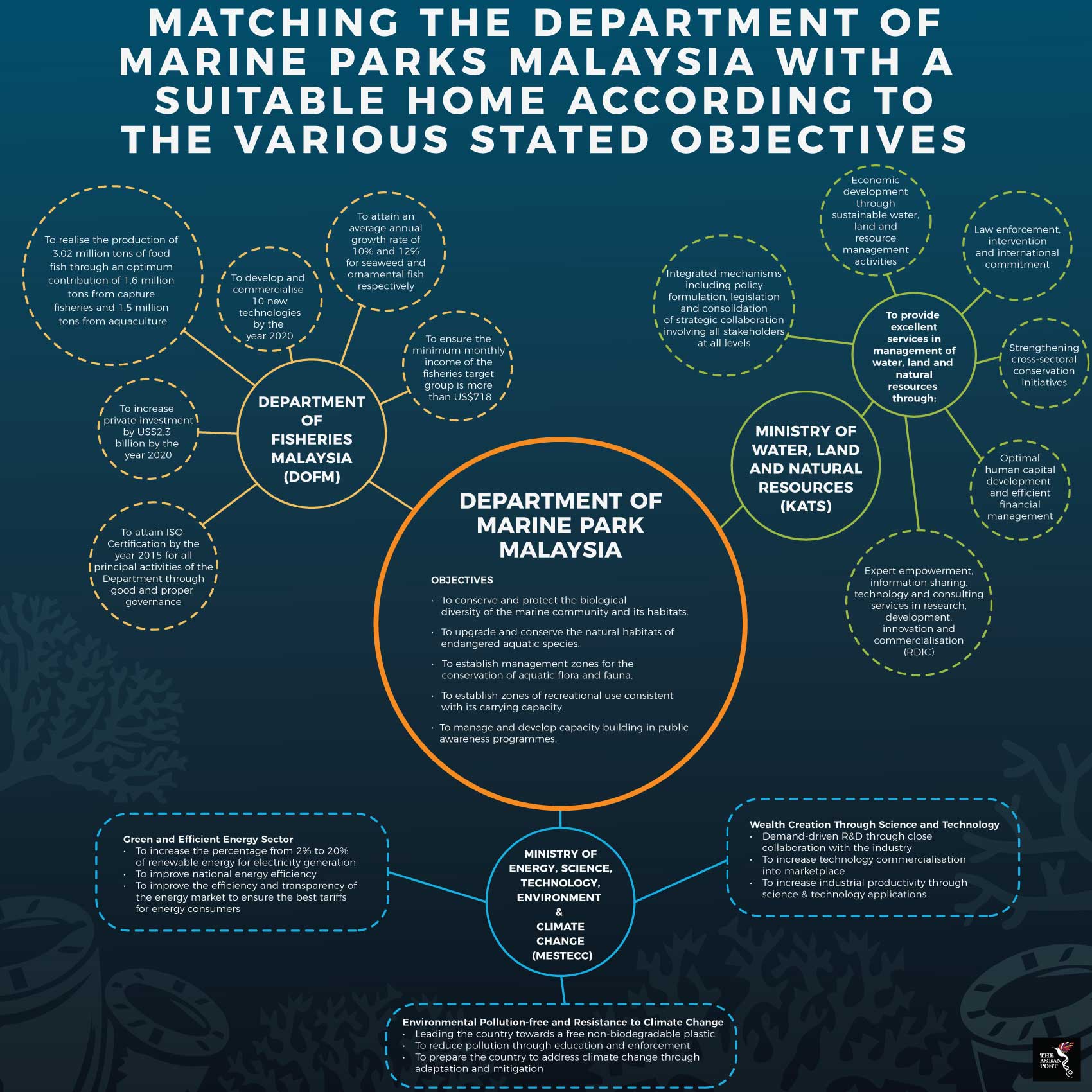

Hyde also suggested that a more suitable home would be with a conservation mandated body, such as the Ministry of Land, Water and Natural Resources (KATS) or the Ministry of Energy, Science, Technology, Environment and Climate Change (Mestecc). The terrestrial counterpart of DMPM, the Department of Wildlife and National Parks (Perhilitan), for example, is parked under KATS.

Source: Websites of MOA, KATS, Mestecc and DMPM.

At its commencement in 1983, the DMPM was born as a section under the MOA, provided for under the Fisheries Act 1985, in response to declining marine fisheries. The goal of DMPM’s establishment was to protect, conserve and manage in perpetuity representative marine ecosystems of significance, particularly coral reefs and their associated flora and fauna, as well as to nurture public awareness on Malaysia’s marine heritage.

It was later realised that, in many cases, traditional fisheries management approaches were not successful in preventing overfishing and dwindling fish stock. There was also space and capacity for DMPM to offer more than just fisheries management. In 2004, the Marine Park Section was shifted to the MNRE with new vision, mission, objectives and functions to complement the overall vision of the conservation-driven ministry. However, throughout its stint with MNRE, the relationship between DMPM and DOFM was riddled with issues related to assets and enforcement authority.

Iconic species left unprotected

The move also raised some major questions on where non-seafood marine life stands under the management of DOFM. This includes iconic species like dolphins, whales, dugongs, turtles and sharks, many of which have high tourism value and, more critically, are globally listed under the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN’s) Red List as being ‘Vulnerable’, ‘Endangered’, or ‘Critically Endangered’.

Up until 2010, non-seafood marine wildlife was protected under the Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1972. With the gazettement of the Wildlife Conservation Act in 2010, all non-commercial marine wildlife species were excluded as they were already protected under the Fisheries Act 1985. However, under the act and the Fisheries (Control of Endangered Species) Regulation 1999, these species are mistakenly and misleadingly defined as “fish”.

For the many iconic species that fall under marine mammals or reptiles, as well as non-seafood fish species like sharks and some rays, the wrong definition constitutes a non-priority of their conservation under DOFM. This can be seen through DOFM’s staffing and skilling, as well as focus initiatives implementation.

For example, in 2015, under the management of DOFM, the leatherback turtle population in Peninsular Malaysia was declared ‘functionally extinct’, much of which was the result of the lack of understanding of the impact of turtle eggs’ incubation temperatures and sex-ratios. Another example, a DOFM-driven coral farming initiative on Terengganu’s Pulau Bidong targets local and international coral trading for aquariums, despite an obvious need for coral rehabilitation due to declining levels of living corals in the waters of Peninsular Malaysia.

While it is completely acceptable for the MOA and DOFM to prioritise intensifying yields of capture fisheries, the removal or weakening of conservation-focus from the one agency that shoulders the responsibility for marine resource management will spell the end of many amazing things from Malaysian waters. Unless a major overhaul of values and goals takes place in the extractive-driven ministry, perhaps a new home is needed for the travelling department.

Related articles:

Marine protected areas increasing fish stocks

Protecting Indonesia’s marine resources