The South China Sea dispute would be one of the more pertinent priorities on the minds of diplomats as they head to Singapore for the 33rd ASEAN Summit and other related meetings.

The dispute has for the longest time been a thorn in the flesh of relations between claimant Southeast Asian states – the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam and Brunei – and China, and for good reason.

It is one of the key arteries of global trade, carrying an estimated one third of global shipping amounting to trillions of dollars. The area is also rich in hydrocarbon resources. Estimates by the United States Energy Information Administration indicate that 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of gas lies under the seabed of the South China Sea.

Code of conduct

Between agreeing on whether the code of conduct should be binding and China’s continued attempts to woo states into its orbit of influence with the promise of cheap credit, progress towards a peaceful resolution of the dispute has been stiflingly slow.

ASEAN and China have clung on to a non-binding Declaration of Conduct (DOC) signed in 2002 which has been long overdue for change. However, the manner in which this change materialises, depends on the negotiations of a Code of Conduct (COC).

During the ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting last August, a single draft document was concluded, which would form the basis for further negotiations for a COC in the South China Sea. Hailed as “yet another milestone” in talks regarding the dispute, observers have noted that even if a Code of Conduct is concluded successfully, it still would not spell the end of the dispute.

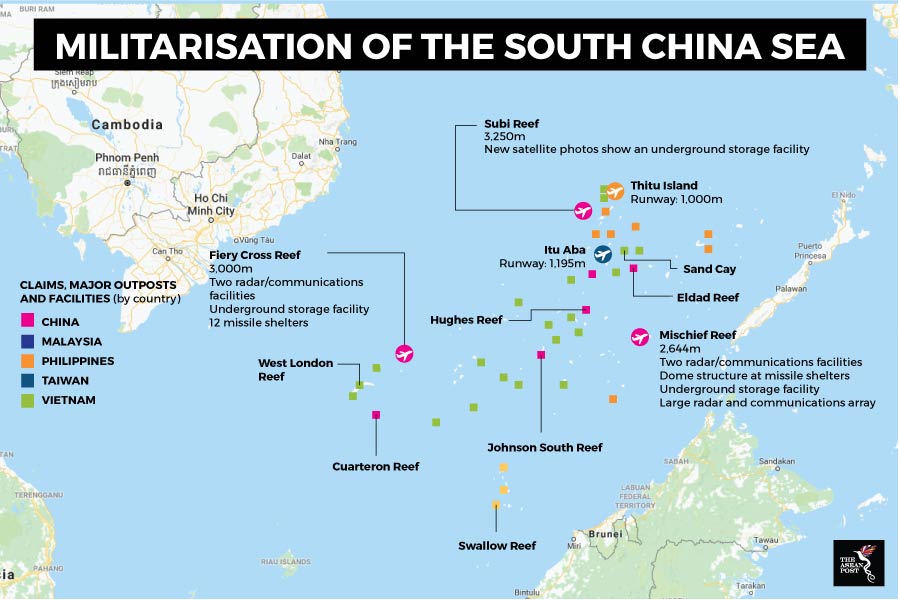

However, a nod towards the COC could be construed as yet another carrot dangled by China to further assert its dominance in the region. Having already made significant gains in island reclamation and militarisation of several features in the disputed region, China can afford to come to the table now to negotiate and influence the narrative in favour of its agenda.

Even in a best-case scenario if all parties including China agree to a COC, it is likely that if things don’t go its way, Beijing could possibly disregard the COC altogether – having made a similar move after losing an international arbitration case to the Philippines.

Source: Various

Indo-Pacific focus

Herein, ASEAN member states could do with a little help from the United States (US) to balance out Chinese aggressiveness. However, the conspicuous absence of US President Donald Trump at the summit this time around sends a negative signal to his counterparts in Southeast Asia, who don’t want to be living in a region that is dominated completely by Beijing.

The US delegation is led instead by Trump’s second in command, Mike Pence and national security advisor, John Bolton.

China’s actions to establish an air defence zone around the contested islands, reefs and atolls have not been received too kindly by the US and other claimant states. The US in a statement called on the Chinese to withdraw their missile systems and avoid “addressing disputes through coercion or intimidation.”

Beijing on the other hand, has demanded for the US to discontinue its freedom of navigation operations (FONOP) as they perceive such actions as undermining Chinese authority and security interests.

Nevertheless, the Trump administration insists that the President’s absence doesn’t signal a lack of focus he has over concerns – especially ones related to China – in this part of the world. In an opinion piece published by the Washington Post, Pence reiterated the US’ commitment to the Indo-Pacific region.

The US, he said “seeks collaboration, not control” and will continue working with likeminded nations throughout the region to advance shared interests. He also added that the US would stand up to anyone who threatens its core values – a thinly veiled jab at Chinese actions in the region.

Despite the diplomatic nitty gritty with negotiating the DOC, it seems to be the best bet in brokering a long-term solution to the dispute. However, as negotiations continue, ASEAN would be much the wiser by including the US – whether formally or informally – in discussions as a buttress against China.

Doing so will nonetheless irk Beijing and could dial back progress towards dispute resolution. Or, it could be ASEAN’s time to shine in displaying its versatility and resilience in managing the interests of two global powers, whilst ensuring the region come off unscathed.

Related articles:

Is Beijing unstoppable in the South China Sea?

Is minilateralism the way forward?